Contact lenses contribute to microplastics problem

Arizona State University researchers say throwing contact lenses down the drain at the end of their use could be contributing to microplastic pollution in waterways.

The inspiration for this work came from personal experience, said researcher Dr Rolf Halden. "I had worn glasses and contact lenses for most of my adult life, but I started to wonder, ‘has anyone done research on what happens to these plastic lenses?’" His team had already been working on plastic pollution research, but couldn't find studies on what happens to contact lenses after use.

"We found that 15 to 20 percent of contact wearers surveyed are flushing the lenses down the sink or toilet," says Ph.D. student Charlie Rolsky. "This is a pretty large number, considering roughly 45 million people in the US alone wear contact lenses."

Lenses that are washed down the drain ultimately end up in wastewater treatment plants. The team estimates that anywhere from six to 10 metric tons of plastic lenses end up in wastewater in the US alone each year. Contacts tend to be denser than water, which means they sink, and this could ultimately pose a threat to aquatic life, especially bottom feeders that may ingest the contacts, Halden says.

Analyzing what happens to these lenses is a challenge for several reasons. First, contact lenses are transparent, which makes them difficult to observe in the complicated milieu of a wastewater treatment plant. Further, the plastics used in contact lenses are different from other plastic waste, such as polypropylene, which can be found in everything from car batteries to textiles. Contact lenses are instead frequently made with a combination of poly(methylmethacrylate), silicones and fluoropolymers to create a softer material that allows oxygen to pass through the lens to the eye. These differences make processing contact lenses in wastewater plants a challenge.

To help address their fate during treatment, the researchers exposed five polymers found in many manufacturers' contact lenses to anaerobic and aerobic microorganisms present at wastewater treatment plants for varying times and performed Raman spectroscopy to analyse them. "We found that there were noticeable changes in the bonds of the contact lenses after long-term treatment with the plant's microbes," says Kelkar. The team concluded that microbes in the wastewater treatment facility actually altered the surface of the contact lenses, weakening the bonds in the plastic polymers.

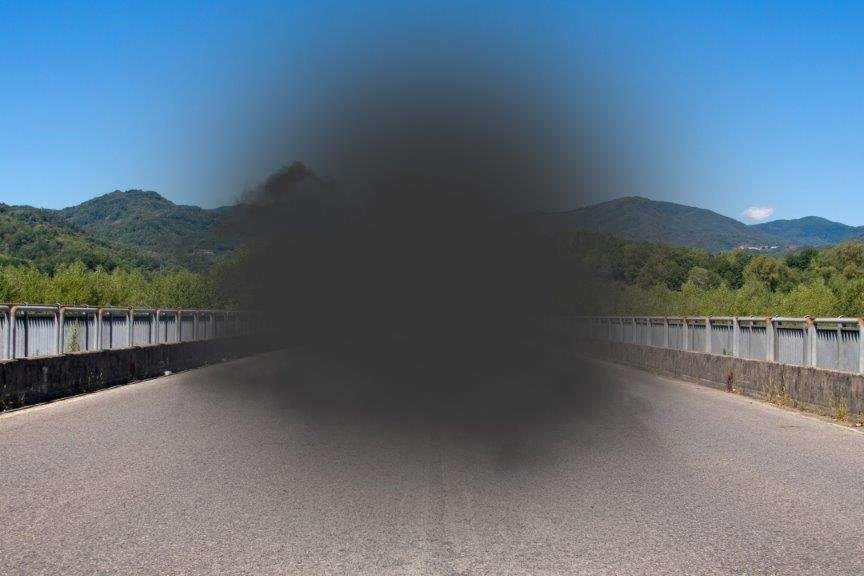

"When the plastic loses some of its structural strength, it will break down physically. This leads to smaller plastic particles which would ultimately lead to the formation of microplastics," Kelkar says. Aquatic organisms can mistake microplastics for food and since plastics are indigestible, this dramatically affects the marine animals' digestive system. These animals are part of a long food chain. Some eventually find their way to the human food supply, which could lead to unwanted human exposures to plastic contaminants and pollutants that stick to the surfaces of the plastics.

The team says it hopes that industry will take note and at minimum, provide a label on the packaging describing how to properly dispose of contact lenses, which is by placing them with other solid waste. Halden says, "Ultimately, we hope that manufacturers will conduct more research on how the lenses impact aquatic life and how fast the lenses degrade in a marine environment."