New markers for eye disease

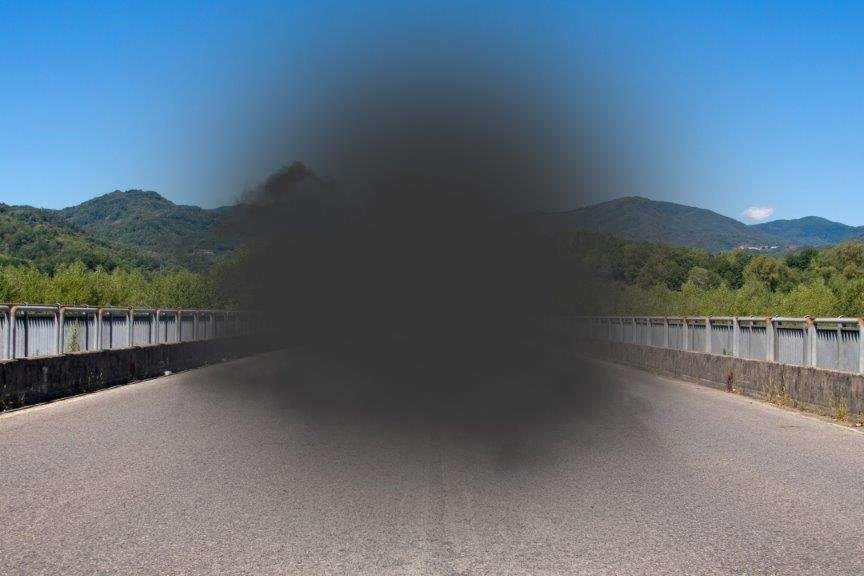

Scientists have discovered 19 new genetic markers that could predict the risk of eye disease, bringing the total number of known variants to 45. The genome-wide study of 25,000 people almost doubles the number of known genetic variants that affect how thick the cornea is, according to findings published in Nature Communications - and could potentially help predict corneal thickness and thus risk of keratoconus, with very high accuracy, at birth.

The head of QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute’s statistical genetics laboratory, Associate Professor Stuart MacGregor, said the discovery of new genetic markers could help predict a person’s future risk of corneal thinning. “Corneal thickness is remarkable because it is one of the most heritable human traits,” he said. “If we mapped more of the genes for corneal thickness, we could predict at birth what a person’s corneal thickness would be with very high accuracy because there are almost no environmental factors that determine it. The discovery of additional genetic markers will help us to reliably predict which people are at a higher risk of keratoconus in the future.”

A/Prof MacGregor said the findings also enhanced understanding of the genetics of connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome and brittle cornea syndrome. “We are finding there is a lot more overlap between what some of these genetic markers do and what was previously thought,” he said. “These discoveries are exciting because they tell us what features could be important in the development of new treatments.”

A/Prof MacGregor said the research did not find an association between low corneal thickness and glaucoma. “It was long thought that having a thin cornea was a risk factor for developing glaucoma,” he said. “However, our findings indicate that there is probably no link between corneal thickness and glaucoma. Instead, it’s likely the thickness of the cornea affects our ability to measure the pressure of the eye.”

The study used data from more than 2000 Australian twins who took part in QIMR Berghofer’s Q-Twin study, which started in 1990, as well as from other collaborative international studies. It included data from the general population, as well as from patients of either European or Asian ancestry who had keratoconus or glaucoma. The QIMR Berghofer-led research was a collaboration with geneticists from around the world.