Post-cataract endophthalmitis

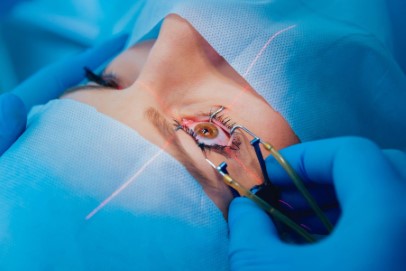

A great deal has been learnt in the last 10 years about the prevention of cataract endophthalmitis, making it a relatively uncommon complication in New Zealand. While it is difficult to isolate all the factors that account for this change in frequency, there are interesting parallels with other types of surgery, including reduced morbidity associated with small incisions, reduction in surgical times, use of gloves, masks and disposable and adhesive drapes.

In addition to these soft changes there have been other well-documented changes in practice. For example, a recent report conducted by the University of Auckland showed the usage of intracameral antibiotics as prophylaxis had increased from 24% in 2007 to approximately 50% by 2016. This change in pattern was no doubt based on the multiple studies performed in the US and Europe which showed a decrease in endophthalmitis when intracameral antibiotics were administered. Other common prophylactic measures used in New Zealand include the use of aqueous betadine iodine as a surgical wash, attention to pre-existing risk factors such as blepharitis and diabetes and, in many cases, topical antibiotics for the first post-operative week. Chlorhexidine is substituted for patients allergic to iodine and many facilities use sub-conjunctival vancomycin if the patient is allergic to cephalosporins, the preferred class of antibiotics for intracameral use.

In spite of the best attempts to prevent post-cataract endophthalmitis, however, infection can still occur.

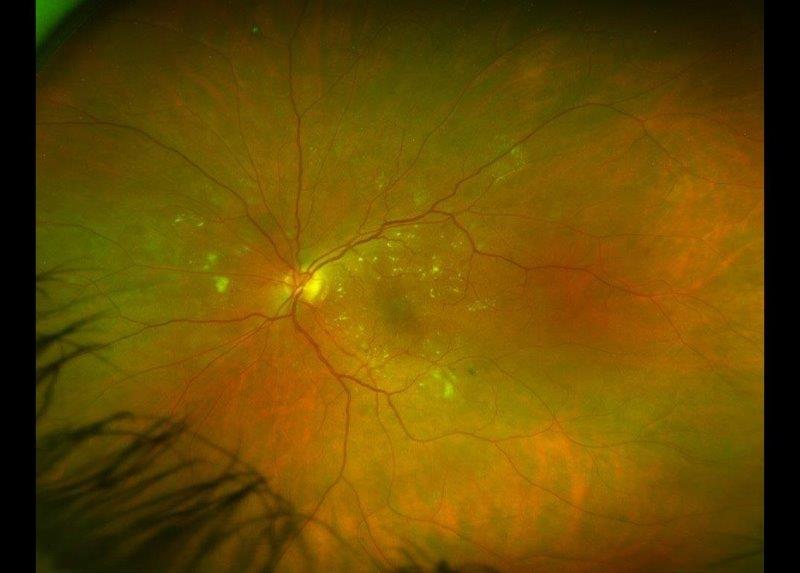

Some years ago, we analysed the common symptoms and signs of endophthalmitis and some previously thought reliable symptoms such as ocular pain were not universal. Equally hypopyon was not always present. In short, the diagnosis is often difficult and the clinical features vary enormously. The continuum includes eyes that have undergone apparently uneventful cataract surgery with a normal post-operative course, yet proven to be culture positive when the aqueous is sampled, and eyes that appear to have “more inflammation” than normal, yet still settle with standard topical treatment protocols to those eyes that are diagnosed as having endophthalmitis. Plus there is the exceptionally rare case, usually neglected, that progresses to panophthalmitis.

For nearly 25 years, the treatment of post-cataract endophthalmitis has been relatively well accepted. A randomised study called the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study, published in 1995, showed for eyes presenting with a clinical diagnosis of endophthalmitis following recent cataract surgery, and providing the presenting acuity was better than PLO (perception of light only) then there was no difference in outcome for eyes undergoing tap and inject as opposed to vitrectomy. Conversely, certain subsets such as diabetic patients did fare better with vitrectomy surgery. Another significant outcome of that study was the finding that intra-venous administration of antibiotics was not helpful in either of the two treatment groups.

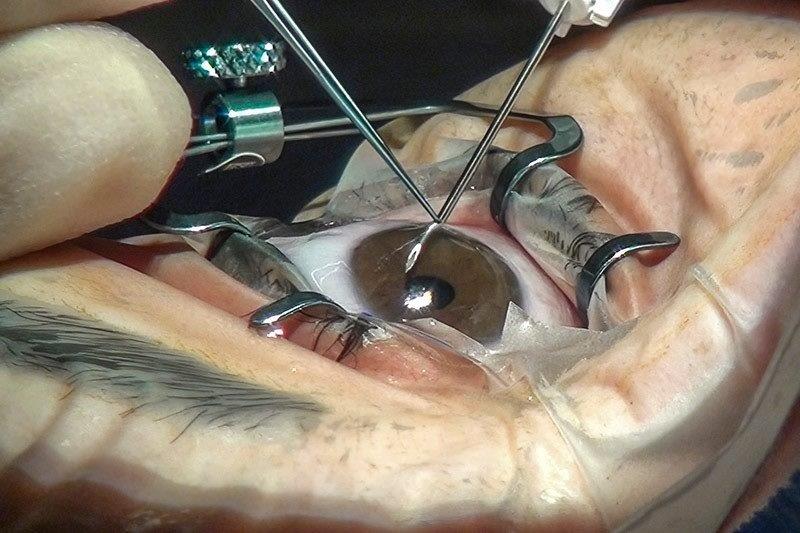

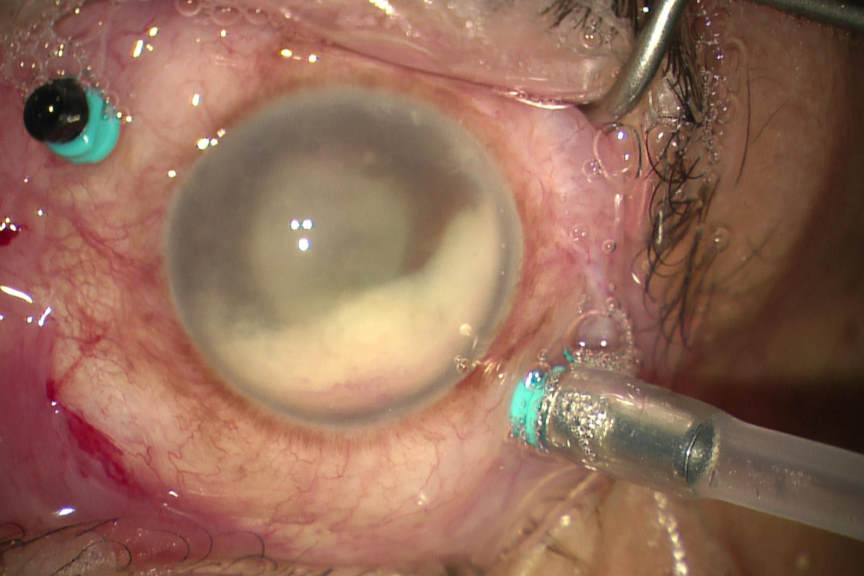

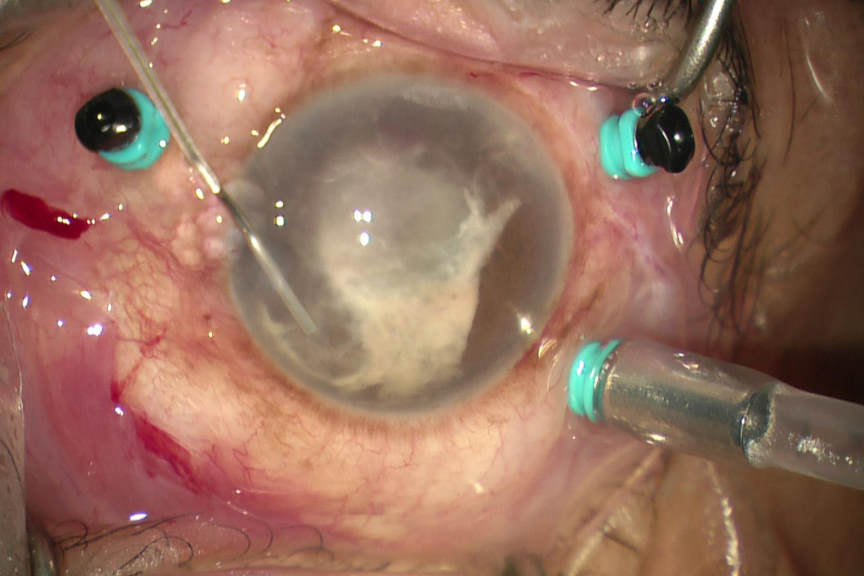

Tap and inject, involves (as the name suggests) inserting a needle, connected to a syringe into the eye followed by aspiration of a vitreous sample, which is then sent to the microbiology laboratory for examination. Antibiotics are then injected into the vitreous cavity, selected to treat empirically both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. This technique has not changed in 25 years and neither has the outcome; meaning approximately 15% of patients will have acuities less than 6/60, and 5% will have no perception of light. Conversely vitrectomy surgery has advanced greatly over the last 25 years with both the speed and efficiency of the cutter having been improved greatly and the size of the vitrector becoming significantly smaller. Typically, 25 gauge instruments are used, equating to less than 0.5mm. Furthermore, the viewing systems have greatly improved. So, the tide of technology has created a trend to perform vitrectomy on all eyes with presumed endophthalmitis following cataract surgery. The hurdle to perform such surgery has also lessened, as the surgery is less invasive. The surgery is usually performed under local anaesthesia; there are more centres in New Zealand that undertake VR surgery and importantly greater access to oncall VR surgeons.

Anecdotally, our experience suggests vitreous biopsies are more likely to be culture positive than those cases where the vitreous has been aspirated into a syringe. That, potentially, is an important consideration when antibiotic resistance appears to be increasing. There is also the suggestion that there is a decreased need to perform additional surgeries with a primary vitrectomy as opposed to the traditional tap and inject. Our local experience also indicates that the functional improvement is better with vitrectomy surgery and that may be related to better clearance of contaminated vitreous with removal of the toxic soup in the eye. We have also found eyes that have undergone vitrectomy have faster rates of recovery and become culture negative more quickly.

Twenty-five years ago those differentials didn’t exist, but if the current trend and shift to vitrectomy is substantiated with better outcomes then we can be more optimistic about the future when managing eyes with post-cataract endophthalmitis.

There are still multiple questions unanswered about endophthalmitis and some of the most puzzling include, why is the anterior chamber culture often negative relative to the vitreous culture? Is that due to bacteria in the anterior chamber existing in planktonic form whereas in the vitreous, the bacteria form biofilms? Why do some patients with bacteria in the anterior chamber at the end of cataract surgery not progress to a clinical infection? Is there as yet an unidentified systemic factor that facilitates the conversion to endophthalmitis? Does that risk factor translate into increased mortality for patients undergoing cataract surgery?

Hopefully some of these questions and improvements in therapy will lead to a continuing improvement in management for patients undergoing cataract surgery and a lessening in the risk of post-cataract endophthalmitis.

About the author

Associate Professor Philip Polkinghorne specialises in retinal, vitreo-retinal and cataract surgery. He has subspecialty training in both medical and surgical retina and is active in clinical and basic science research. He has published over 50 papers, edits ophthalmology journals and contributes as a reviewer to a number of international journals.