An eye on autism

The job of the optics industry is to support those with visual impairment and prevent others from developing it, but for patients who are neurodiverse, such as those with autism spectrum disorder, more has to be done to meet their needs

Imagine walking into a room that is a few degrees too hot, a few decibels too loud and a shade too light. You make your way from this intense space to near darkness, where a strong light is shone in your eyes. You are forced first to squint then to extend your eyelids wide to make sense of symbols just out of your focal reach; then a person you don’t know sprays air unexpectedly and painfully into your eye.

If you’re an optometrist, I can already hear you muttering, “It’s not that bad!” But this perception isn’t mine, it belongs to my 12-year-old son Isaac, who is autistic, and for whom an eye test is absolute torture.

Not only does Isaac find aspects of the testing process physically and emotionally uncomfortable, but he routinely has to deal with not being listened to. Last time we visited our optometrist we’d informed them in advance that the tonometer was not tolerable for Isaac. However, without his permission or any warning, they did the test anyway, believing his adversity to it was just a child playing up. Even when he screamed and ran away from the testing room yelling “It hurts!” the technician insisted the test could not result in pain.

The fact that a minority of us have yet to take the needs of the neurodiverse community seriously deters many of them from attending necessary check-ups, putting their eye health at risk. With up to 90% of autistics affected by sensory issues and as much as 15% of the general population experiencing sensory discomfort, efforts to make change in this area are sorely needed.

Thankfully, Autism NZ is taking a lead on this, having put together a sensory processing checklist to help ECPs understand their patients’ needs, plus a guide for successful interactions with neurodiverse people.

"There are many barriers that autistic people face when accessing healthcare. Often chief among them is professionals' lack of understanding and awareness of autism, or lack of training in how best to support autistic patients,” says Kirsti Whalen-Stickley from Autism NZ. “To be inclusive and to support autistic people, we encourage all healthcare professionals to develop a good understanding of autism and how it may impact a person's experience accessing their service.”

Some optometrists have already taken the initiative and designed their practice to be more welcoming for neurodiverse patients, especially if they work with kids. Taryn Johnn, a behavioural optometrist at Ocula regularly works with autistic children and young adults.

“For our kids, and in particular our autistic patients, we make the eye examination a fun and interactive experience. All kids are encouraged to ask questions and we explain each test before we do it,” she says.

“Some autistic kids need to touch things, so we give them the testing targets to hold and feel. Some kids cannot sit still and we don’t let that bother us when testing – if they want to get up and stretch or walk around a bit during the test, we allow them to. We want them to feel comfortable in the testing environment. We can do all the motility assessments, amplitude of accommodation assessment, NPC, near cover test, colour vision assessment and stereopsis testing without them having to leave their parent's side and sit in the big chair. Once they feel comfortable, we can move them to the testing chair.”

Johnn says they also make provision for patients with a learning disability, such as using an iPad with the Kay Crowded Picture chart app for VA testing when a patient does not know the alphabet (this test can be done at 3m or 1.5m and the picture size adjusted accordingly) or for non-verbal patients they use shape-matching charts.

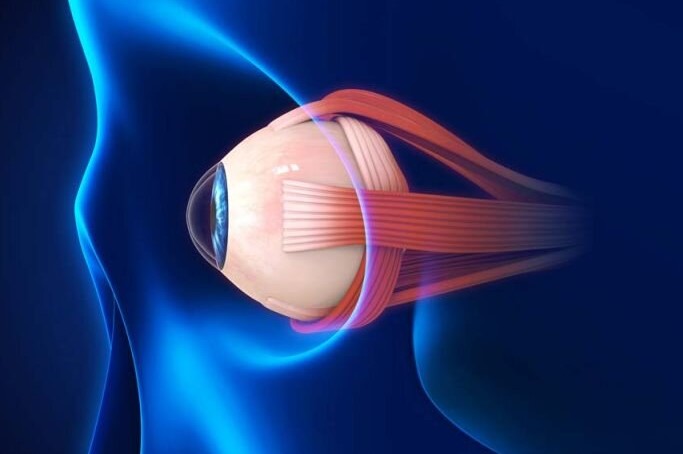

“For an autistic patient, a good objective assessment is always important – observe their eye muscle movements on motilities and cover test. Retinoscopy and MEM ret for near assessment are handy tools, too” says Johnn. “Having a test chart that plays a fun video when performing retinoscopy makes it easier to hold the patient's attention on the chart.”

Johnn says a good rule is to work quickly and adapt to the patient’s needs. “If they do not want to do a particular test, move on; do something else, come back and try that test again later. If it is clear they have had enough of the eye test, we stop, even if we haven’t finished; we can always come back on another day and pick up where we left off. We want to keep the experience positive.”

With the Ministry of Health estimating 1 in 100 Kiwis are affected by autism spectrum disorder (in the US, 1 in 54 eight-year-olds was diagnosed in 2016), it is more important than ever that we work to make optometry as accessible as possible. The specific needs and challenges that each individual may face in the setting will vary, so being flexible, understanding and making appropriate adaptations is important.

Autism NZ offers a course called Framework for Autism in NZ (FANZ), run throughout the country to encourage healthcare professionals to adapt their practices to be inclusive and

supportive. You can find out more by visiting www.autismnz.org.nz

Six simple adaptations for autistics

- Provide information in advance in a format that is suitable for the client. For children this can be a ‘social story’

- Determine sensory needs and work to meet them

- Introduce yourself and your team to help build trust

- Allow extra time for appointments and be prepared to stop

- Offer a 'practice run' to allow the person to familiarise themselves with the space, tools and process

- Adapt your communication style to make it accessible to the client. This might include speaking clearly and directly, providing images about what is coming next or written information and allowing extra time for the client to respond

Freelance writer Jai Breitnauer divides her time between New Zealand and the UK (pandemic restrictions allowing). She lives with her husband and two children in Bristol and is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.