Eye-signal blending research re-examines Nobel-winning insights

Look at an object, cover one eye at a time and the object appears to jump back and forth. Stare at it with both eyes and we take for granted a complicated brain process combining the signals into one, giving us a clear view and proper depth perception. That happens the moment those dual signals enter the visual cortex in the brain, say a team of Vanderbilt University researchers, whose finding contradicts one which garnered a 1981 Nobel Prize in physiology.

Vanderbilt assistant professor of psychology Alexander Maier and PhD student Kacie Dougherty used computerised eye-tracking cameras plus electrodes that can record single neuron activity in a particular area to make their discovery. “Our data suggest that the images the two eyes see are merged as they arrive in the neocortex and not at a later stage of brain processing, as previously believed,” said Maier, adding this is a major leap in our understanding of how the brain combines this information, which could have a whole host of applications to help combat childhood eye conditions.

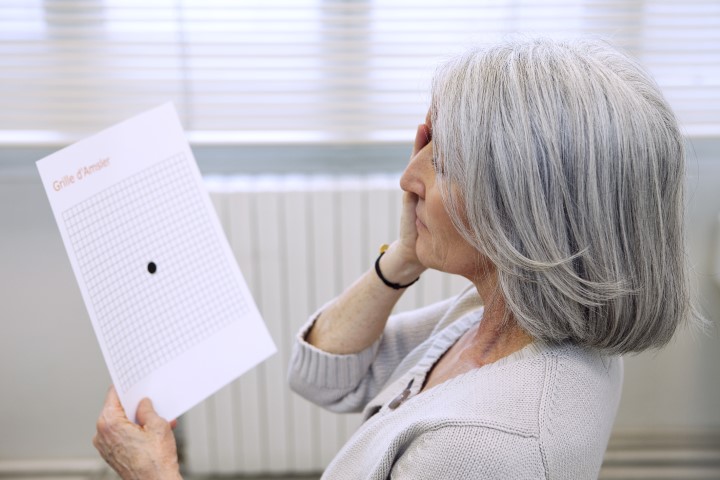

Knowing precisely where the signals meet and how the brain processes them is vital to treating amblyopia or reduced vision in one eye because the brain and eye aren’t working together properly, he said. The current standard treatment is placing a patch over the working eye in an effort to jumpstart the “lazy” one, but if paediatric eye specialists miss the short window when the problem can be fixed, it’s typically permanent, he continued. “So, knowing which neurons are involved in the process opens the door to targeted brain therapies that reach well beyond eye patches.”

There are six functionally distinct layers in the primary visual cortex, said Dougherty. “We thought the initial processing happened in the upper layers, but it’s actually in the middle. That’s vital information for developing treatments.”