Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri, is a syndrome that is defined by clinical criteria that includes increased intracranial pressure and its associated signs and symptoms, normal cerebrospinal fluid composition and no other cause of intracranial hypertension evident on neuroimaging or other evaluation.

Epidemiology

IIH has an incidence rate in the general population of between 0.5-2/100000/year, with the disorder most typically seen among obese women of childbearing age where the incidence is between 12-20/100000 people/year¹.

Clinical features

Patients usually present with a variety of symptoms indicative of elevated intracranial pressure, the more common ones being headache, transient visual obscurations and pulsatile tinnitus². Patients with IIH may develop diplopia secondary to VIth nerve palsy, which is a false localising sign. That is, there is no pathology along the course of the VIth cranial nerve, rather the VIth nerve palsy is the stretching/compression of the long nerve against the petrous ligament of the ridge of the petrous temporal bone. Other common non-visual symptoms include nausea, vomiting dizziness neck and back pain. Less common visual symptoms are retrobulbar pain and sustained visual loss.

Clinical examination reveals papilloedema with an otherwise normal neurological examination. The importance of papilloedema is that it raises the possibility of damage to optic nerve function if the disc swelling is sustained. It is important to remember that visual acuity is preserved in early papilloedema. Visual field testing may reveal an enlarged blind spot, which is a reflection of the papilloedema rather than decreased optic nerve function. However, prolonged or extremely elevated intracranial pressure may result in optic nerve compromise. This manifests as visual field defects in the early stages. With progression of optic nerve damage there is decreased visual acuity and loss of colour vision. The most important long-term sequelae of IIH is visual loss. Therefore it is critical to perform regular assessment of optic nerve function, which includes visual acuity, formal automated field testing, colour vision and fundus examination.

Investigations and diagnosis

The diagnosis of IIH requires normal neuro-imaging, which includes either a CT venogram or MR venogram so that venous sinus stenosis/thrombosis can also be excluded. In addition, it is important to exclude space occupying lesions or abnormal meningeal enhancement. Neuroimaging findings that are consistent with elevated ICP include flattening of the globes, fluid in the subarachnoid space around the optic nerves, an empty sellae or small ventricles. Venous sinus narrowing may also be a sign of raised ICP, although in some cases it may be the underlying cause.

If papilloedema is present in normal neuroimaging, then a lumbar puncture is required to both measure the opening pressure as well as evaluate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition.

Secondary causes - medications

- Tetracycline antibiotics

- Excess vitamin A and its metabolites (retinoids)

- Hormone-related (thyroxine, growth hormone, tamoxifen)

- Children only (nitrofurantoin, sulphonamides, nalidixic acid)

Systemic conditions

- Chronic anaemia

- Addison’s disease

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

Natural history

Vision loss can manifest both early or late in the disease course and often does so without the patient realising. Such vision loss commonly occurs over a long course of months to years, ranging from mild defects with enlarged blind spots, nasal defects and generalised depressions to permanent blindness, which is the main morbidity associated with idiopathic intracranial hypertension³. Visual field defects were observed in monitored patients with a proportion of 56-80% on automated perimetry though 67% of these defects were mild/minimal and patients were reportedly asymptomatic with these defects⁴. In general, visual prognosis appears to be good with treatment with 51-60% of patients were found to have stable or improved visual fields and only 10% experiencing worsening visual function³. Recent studies estimate blindness or severe visual impairment rates to range between 1-10%⁵.

Recurrence of IIH has been found to occur in patients after resolution of symptoms and recovery from the first episode or after stability of months and years at a reported rate of between 8.3% to 52%⁶. Recurrence was associated with cessation of acetazolamide treatment due to non-compliance or intolerance of the medication as well as weight gain⁶.

Approximately 3% of patients with IIH experience a fulminant variant of the disease with rapid vision loss within four weeks of symptom onset requiring surgical intervention, but unfortunately most have very poor visual outcomes⁷.

Factors predicting poor visual outcome or treatment failure:

- Persistent vision loss with poor visual acuity

- High grade papilloedema - presence of nerve fibre layer haemorrhage correlated with severity of papilloedema

- Male sex

- >30 transient visual obscurations/month

- Morbid obesity

- Black race

- Systemic hypertension

Management

The treatment of IIH has two major goals: Preservation of vision and alleviation of symptoms, mainly headache. Any causative medications identified should be ceased if appropriate. Some patients with normal vision and minimal symptoms require no treatment other than monitoring.

Treatment options can be categorised into three groups:

1) Weight loss

Weight loss has been shown to be a successful treatment with a decrease in 4.2kg/m2 BMI being associated with 66.7% improvement in papilloedema, 75.4% improvement in visual fields and 23.2% improvement in headaches⁸.

Bariatric surgery is an alternative option to achieving weight loss with an average BMI reduction of 17kg/m2, average decrease of 18.9cmH2O in opening pressure, with 90-100% resolution of papilloedema and improvement in headache symptoms and visual fields⁸.

2) Pharmaceutical treatments

- Acetazolamide: The medication with the strongest evidence for treating IIH⁹.

- Topiramate: Can serve as an alternative to acetazolamide. Its role as a prophylactic migraine medication contributes to headache management and its side effect profile also contains appetite suppression,which can contribute to weight loss.

- Corticosteroids are not recommended as long term or routine therapy,given that withdrawal of steroids has shown severe rebound in intracranial pressures and vision loss,in addition to weight gain from corticosteroids.

3) Surgical treatments

The general indication for surgical intervention has been for cases with rapid onset and severe vision loss OR progressive vision loss despite full medical therapy, OR patients who do not tolerate medical therapy and are debilitated by symptoms. Less than 9% of patients undertake surgical management¹⁰.

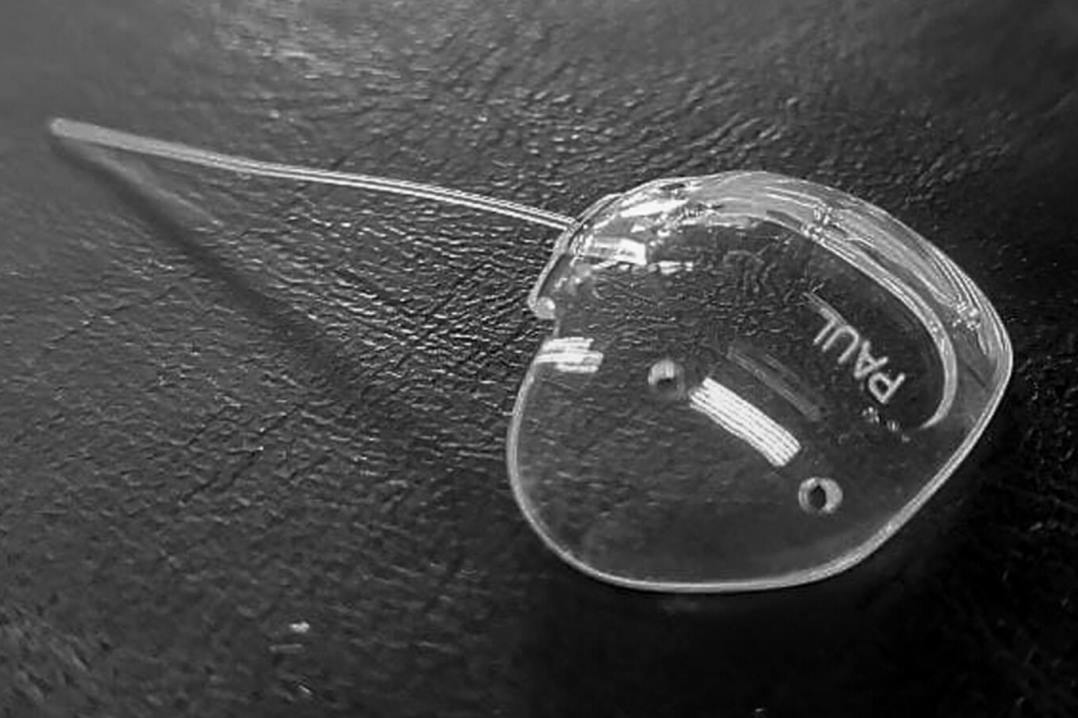

- Optic nerve sheath fenestration (OSNF) involves an incision of the optic nerve sheath to produce an opening releasing CSF and consequently reducing ICP. The procedure has shown significant improvements in vision with medically refractive IIH patients. Those with severe vision loss and minimal headache are most appropriate to undergo ONSF¹¹.

- CSF diversion procedures: ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) orlumboperitonealshunt (LPS). Benefits from either shunt procedure has been shown to result in improvement in vision, headaches and papilledema¹².

- Venous Sinus Stenting (VSS) is a newer approach in managing IIH,addressing the stenosis of intracranial transverse venous sinuses and pressure gradient found across the stenotic segments in relation to IIH. It has been shown to have an excellent complication profile, low relapse rate, lower need for repeat procedure/revision and comparatively satisfactory results in improvements in vision, papilledema and headache,with better outcomes compared to OSNF and CSF diversion procedures¹³. However, VSS is indicated for patients with a confirmed pressure gradient between stenotic segments of the venous sinuses and these results may not apply to all patients with IIH.

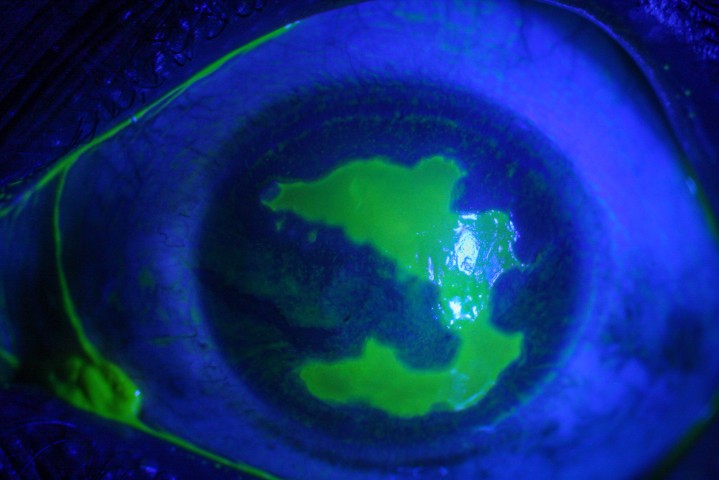

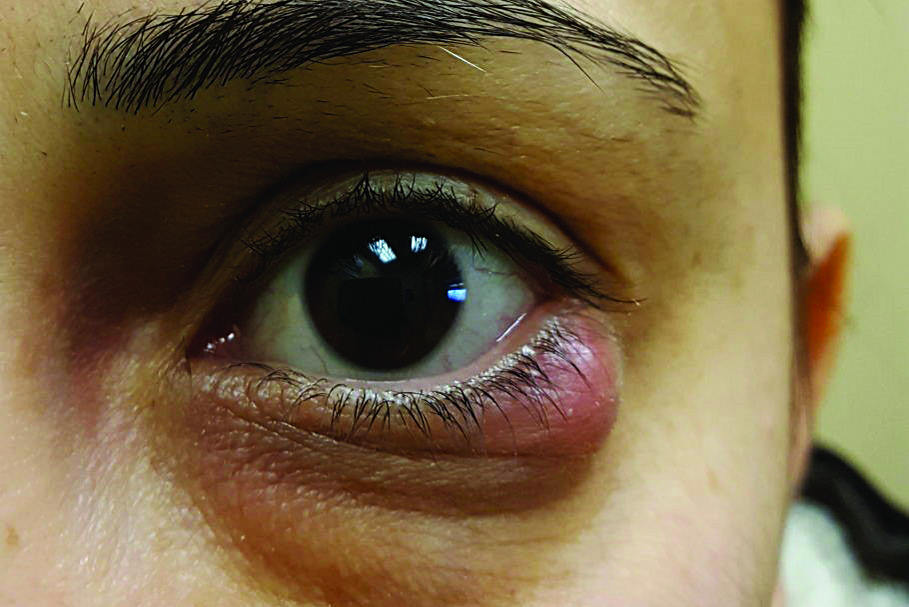

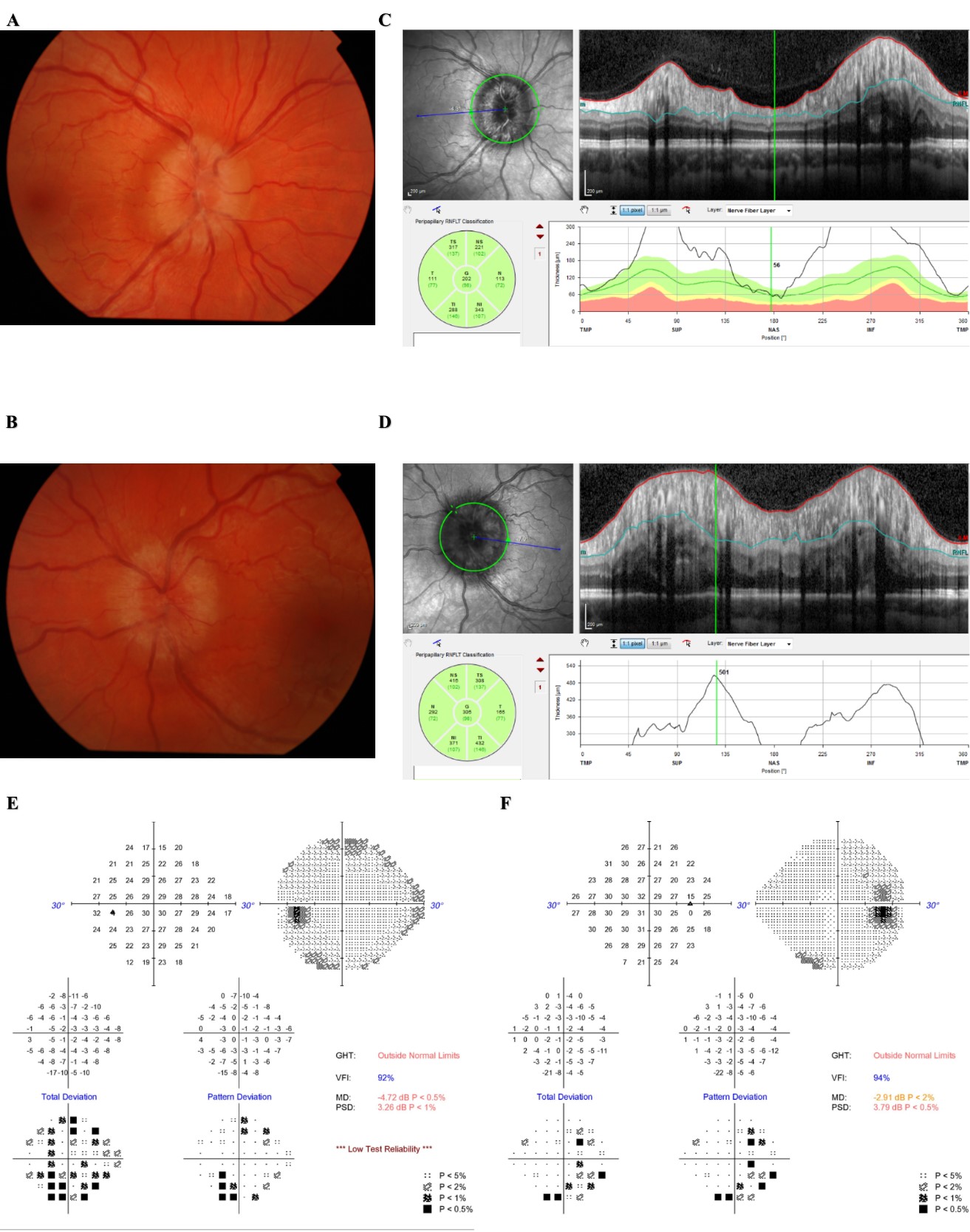

Fig 1: Fundus photographs and OCT can contribute to diagnosis and monitoring of IIH and papilloedema. (A) Fundal photograph of right eye and (B) Fundal photograph of left eye with corresponding OCT scans of right eye (C) and left eye (D). Humphrey visual fields of the same left eye (E) and right eye (F).

A and B show optic disc swelling with elevated discs and peripapillary haloes. C and D shows increases in retinal nerve fibre layer thickness. Both E and F show enlarged blind spots and D shows early stages of generalized constriction of the visual field.

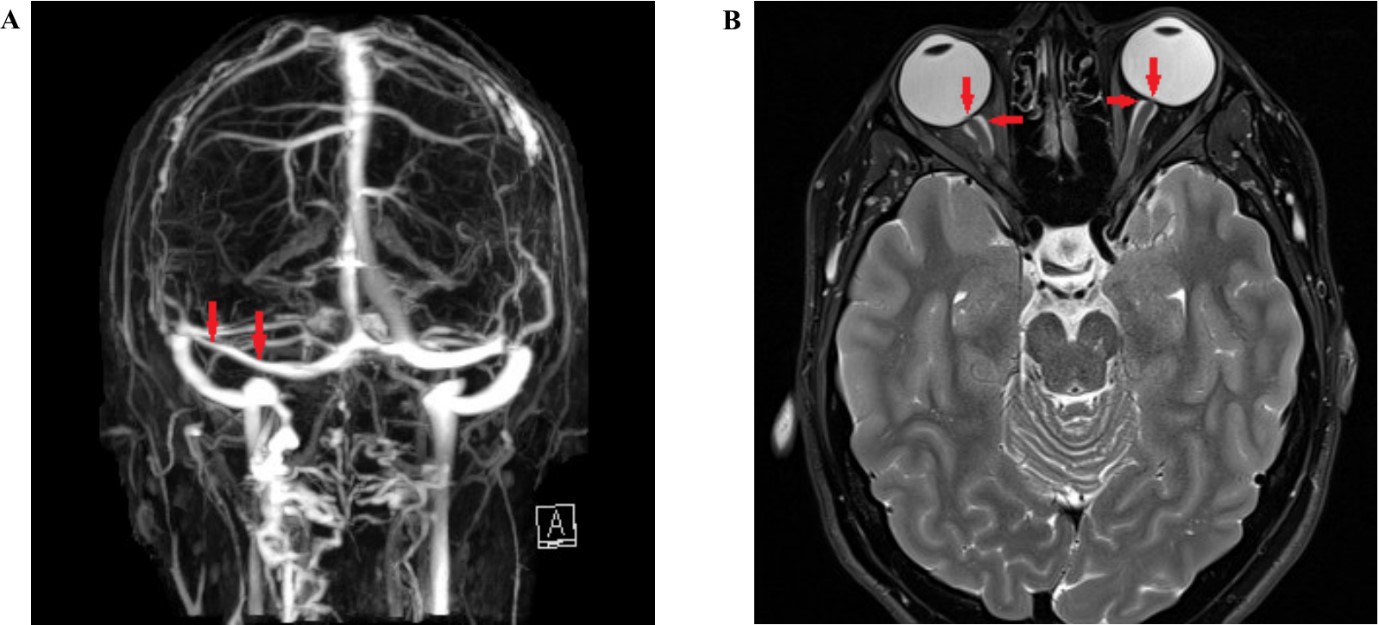

Fig 2: Neuroimaging features of IIH

(A) MRI venography showing narrowing of the left transverse sinus (arrow). (B) T2 weighted MRI; axial; flattening of the globes (vertical arrows) and distension of optic nerve sheaths (horizontal arrows).

References

1. Markey K, Mollan S, Jensen R, Sinclair A. Understanding idiopathic intracranial hypertension: mechanisms, management, and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(1):78-91.

2.Wall M, Kupersmith M, Kieburtz K, Corbett J, Feldon S, Friedman D, et al. The idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial: clinical profile at baseline. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(6):693-701.

3.Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991;114 (Pt 1A):155-80.

4.Rowe F, Sarkies N. Assessment of visual function in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study. Eye (Lond). 1998;12 (Pt 1):111-8.

5.Best J, Silvestri G, Burton B, Foot B, Acheson J. The Incidence of Blindness Due to Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in the UK. Open Ophthalmol J. 2013;7:26-9.

6.Ko M, Chang S, Ridha M, Ney J, Ali T, Friedman D, et al. Weight gain and recurrence in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a case-control study. Neurology. 2011;76(18):1564-7.

7.Thambisetty M, Lavin P, Newman N, Biousse V. Fulminant idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2007;68(3):229-32.

8.Manfield J, Yu K, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Ashrafian H. Bariatric Surgery or Non-surgical Weight Loss for Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension? A Systematic Review and Comparison of Meta-analyses. Obes Surg. 2017;27(2):513-21.

9.Wall M, McDermott M, Kieburtz K, Corbett J, Feldon S, Friedman D, et al. Effect of acetazolamide on visual function in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild visual loss: the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial. JAMA. 2014;311(16):1641-51.

10.Mollan S, Aguiar M, Evison F, Frew E, Sinclair A. The expanding burden of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(3):478-85.

11.Satti S, Leishangthem L, Chaudry M. Meta-Analysis of CSF Diversion Procedures and Dural Venous Sinus Stenting in the Setting of Medically Refractory Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(10):1899-904.

12.McGirt M, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri-associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2004;101(4):627-32.

13.Kalyvas AV, Hughes M, Koutsarnakis C, Moris D, Liakos F, Sakas DE, et al. Efficacy, complications and cost of surgical interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017;159(1):33-49.

Dr Kevin Liu is a junior doctor working as the Optic Nerve Clinical Research Fellow under Professor Helen Danesh-Meyer at the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Auckland as well as the Department of Ophthalmology, Greenlane Clinical Centre, Auckland District Health Board.