Optometry’s sex change?

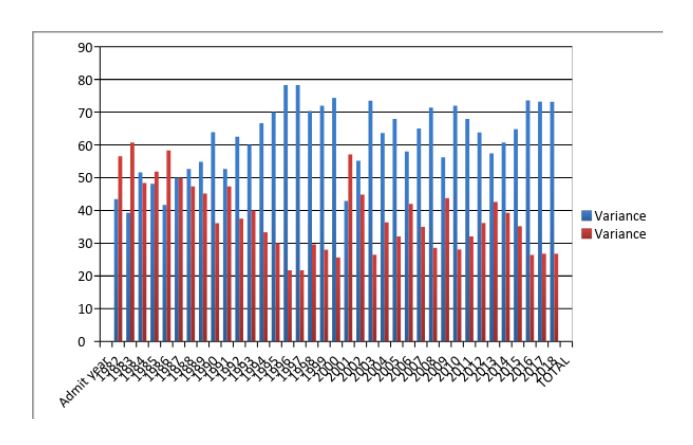

The ’80s: bad hairdos, shoulder pads, high-waisted jeans and male optoms vastly outnumbering female optoms. Then, in 1987, things changed. For the first time, female optometry students outnumbered males and this has been the pattern ever since, except for 2001 (see Table 1).

This year, 73% of students enrolled in the Bachelor of Optometry course at the University of Auckland were female. Today, female optometrists outnumber males by 2:1 in the under 40 age group, which is vastly different from the 40-69 age group where it’s nearly 1:3, females to males. Across the ditch things are similar, with 78% of Australian optometry registrants now female, lifting overall female optometrists’ numbers by 901 since December 2012.

Feminisation is defined as a ‘profound shift from males to females’, so is this what’s happened to the region’s optometry profession? If it is, what does this mean for the profession, for gender diversity? Does it matter if our profession is dominated by women? Will there, could there, be an effect on our patients?

Table 1. Percentage of female and male optometry applicants at Auckland University

Inside and outside the workplace

In general, the gender gap across the workplace is decreasing. In 2016, 61% of women were employed, compared with 52% in 1986, but there is still a large divide in the types of jobs the sexes do. Most librarians, care workers and counsellors are women, while most glaziers, brick-layers and engineers are men. Is it because women are the main carers for children that they gravitate toward caring professions? It certainly seems that men veer towards jobs working with things while women prefer working with people. Nine out of 10 nurses are women and, in more recent times, teaching and other health professions such as pharmacy, dentistry and general practice medicine, have come to be dominated by women. Researchers paid to look at these things, suggest boys are encouraged (and thus assumed) to be more analytic, outgoing and aggressive, while girls are encouraged (and equally assumed) to be more nurturing, passive and dependent.

In New Zealand, women still take on the lion’s share of childcare, often in addition to working. A 2010 survey showed, on average, women do double the number of childcare hours (and housework hours) than men, with a shocking 12% of fathers contributing no childcare hours at all. This imbalance means women are more likely to work part-time; a fact borne out in optometry, with research from the New Zealand Association of Optometrists (NZAO) showing women take on more part-time and locum roles and are significantly more likely to take a career break.

Researcher Orrin Huang from the University of Sydney Business School, who wrote his thesis on Looking through gendered lenses – the feminisation of optometry in Australia, says flexibility is very attractive to most women who still consider the time when they choose to have children a very important stage in their lives.

“The optometry profession differs from the majority of other professions as the way it is structured offers flexibility for both parties. If full-timers need to take time off, a locum can step in and vice versa. I also think that optometry allows women who take maternity leave to re-enter the workforce quite easily.”

The gender gap

But because women take on more childcare hours, this impacts their pay, with mums earning on average 17% less than dads. The NZAO survey also showed men are significantly more likely to be self-employed, thus business owners, than women. Interestingly, there are also fewer women in academia, specialisations and leadership roles within optometry; a trend mirrored in other health professions such as dentistry. But why, especially given the feminisation of optometry over the years?

New Zealand’s paid parental leave scheme is one of the least comprehensive in the industrialised world; third worst ahead of Australia and the United States. In 1987, the 52-week unpaid leave period in New Zealand finally became gender-neutral, allowing parents to share leave. More recently, the current government increased the paid parental leave period to 22 weeks, with a view to making it 26 weeks by 2020. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern is leading the way in more ways than one: a sterling example that career and child-rearing can mix.

It’s certainly possible for men to stay at home and enjoy it too. After giving birth to my second child, my husband took on the primary caregiver role last year, staying at home to care for two children under three while I worked. It was hard at first: for me - juggling breast pumps and referral letters in lunch breaks and coping with a few raised eyebrows amongst some people we knew, “Oh, so your husband had a day off work today? How lovely.” - while my husband became a ninja nappy changer, while feeling somewhat lonely as the sole dad in a sea of mums at playgroup. But we made it work and overall it was a tremendously positive experience. Sharing paid work and childcare has given us each an insight into the challenges of each role, while setting an important example for our children, that ‘blue’ and ‘pink’ jobs don’t exist.

The evolution of optometry in NZ

So, what else is bringing about this change in our industry? Historically, optometry was a far more technical profession, focused on the correction of refractive errors. But over the years, the profession has changed dramatically, incorporating a more medical and therapeutic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of ocular pathologies, making it (according to the statisticians) a far more attractive industry to women.

One doyen of the industry, Brian Black from Eyeline Optical, remembers when optometry was “pretty much an all-male profession” with around 12 new male students graduating a year. Then the rules changed, he says, with students being selected primarily on academic merit. Suddenly the number of female optometrists shot up, causing “alarm amongst the optometry profession,” he recalls with a smile.

This trend is similar in other health professions such as pharmacy - when a more structured university course was established, the number of female applicants increased. It seems women move into a profession when it shifts from a learn-on-the job type profession with a (male) gate-keeper to a more organised course where entry is based simply on academic merit.

In 2009, Specsavers entered the market, doubling store numbers in its second year and quickly netting a third of the local optometry market. This created a flurry of new jobs, many part-time, with a company not so fussed about gender, compared with the mainly-male independent business owners at the time.

The importance of gender diversity

But what impact does this increasing lack of gender diversity (once again) have on the optometry profession today? Studies show time and again that having a mix of genders in a profession is better for business. Including people with different backgrounds, outlooks and experiences is beneficial to any industry as it better reflects the client or patient base those businesses serve. Women bring creativity, empathy and problem solving which drives innovation and improves productivity and performance, say economists, who warn against having large gender disproportions, as having more balanced, integrated occupations make an economy more efficient.

Thus, weighing up the economic comments, a lack of gender diversity in optometry is likely to be negative, especially in larger corporate groups which have an influential steer over the future direction of the profession.

The cost of feminisation

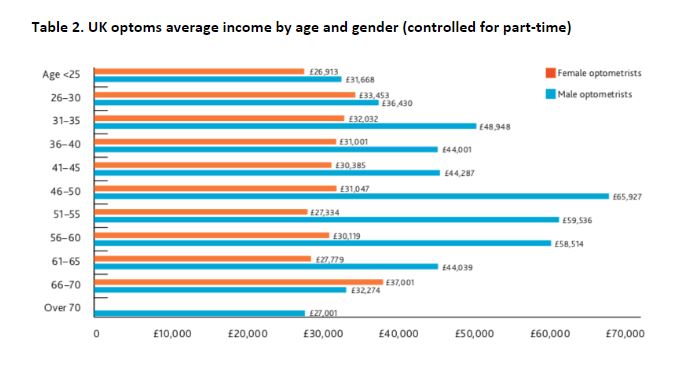

In several professions where the number of women has increased significantly and proportionately, relative pay levels have reduced. Even controlling for skill and education levels, occupations with a greater proportion of females pay less than those with a lower proportion. No figures exist for New Zealand yet, but the optical workforce survey in the UK showed female optometrists consistently earn less, even when adjusting for part-time work (see Table 2). This pay gap is highest in the 46-50 age group, where men earn more than double their female counterparts.

It is believed something similar is happening here, which Huang puts down to the changing nature of optometry in the region. “When Specsavers moved into Australia and New Zealand, it saturated the overall optometry market which in turn reduced wages. Between OPSM and Specsavers, the traditional “mom and pop” style brick and mortar optometrists were being bought out at a dramatic rate. A reduction in wages has traditionally meant that men are driven out of the industry. Once that happens it opens up more opportunity for women to flock into the profession (similar to clerical work).”

The future?

In this humble scribe’s opinion, a little gender swing, say 60:40 in any direction for any profession is probably no bad thing, but when that imbalance gets higher, say more than 70%, like we are seeing in New Zealand optometry today, it is worrying. Diversity is important and I for one don’t want to see a future where optometry is thought of as a female-only profession. Plus, the potential negative impact on job status and pay is something that needs addressing sooner rather than later.

But, even with female optometrists seeking more part-time and locum roles, and favouring urban areas, it seems our optometrist supply is currently meeting demands. In most areas our patients will still be able to find a general optometrist, with those in larger centres having more access to specialities such as myopia control and specialist contact lens fitting or dry eye services. But the impact of having many part-time or locum optometrists should be considered. I hear all the time from my patients about the importance of continuity of care. Patients really value seeing the same optometrist each year, especially those with a complex history of eye conditions or in older age groups.

Given women currently appear less likely to take on leadership roles, the current optometry course should be reviewed to include more training on business ownership and management skills, so women feel more confident about moving into these roles. Plus, as the profession evolves, and optometry continues to extend its reach into the health area, allowing new specialisations, the profession should be marketed as an exciting profession for both men and women. Role models in optometry, especially younger male role models, should be encouraged to provide work experience opportunities and visit schools or universities to encourage new optometry applicants from all points on the gender spectrum.

It has been interesting to take a peek into this world of ours and the changing nature of today’s workplace and despite some of the negative trends I have discovered, I am still excited about the future of optometry in New Zealand.

Ella Ewens is a therapeutically-qualified optometrist at Greenlane Clinical Centre, specialising in CLs, therapeutics and glaucoma, and a writer for NZ Optics.