So you want to set up a dry eye clinic?

It’s become clear, as our knowledge has evolved, that dry eye management, if performed thoroughly, cannot be squeezed into a normal examination as part of a standard eye examination. You wouldn’t expect to perform a full glaucoma work-up within a standard eye examination and neither should you expect to perform a detailed dry eye assessment in this time. This specialised area requires time, dedicated staff and an individualised approach, in the development of the final management plan.

Preliminary testing

The TFOS DEWS II diagnostic process leads us through the most important features of a dry eye assessment. The first critical component is history-taking as this allows the clinician to develop an understanding of the individual presenting patient. In a symptomatic patient, the clinician must first establish that dry eye is the most likely problem. This requires a triaging process, to help differentiate dry eye from other underlying causes of ocular surface discomfort, such as allergy or infection. Having the patient answer such triaging questions, with the aid of a questionnaire either prior to their appointment or via an interview with the assistance of ancillary staff, before diagnostic testing takes place can help streamline the process, especially when it comes to recording successes and failures of previous dry eye treatment attempts. The same is true in determining relevant risk factors. A pre-attendance checklist will allow key information to be passed to the clinician about possible dry eye aetiologies and modifiable risk factors, that will allow for more focused history-taking on site and can be addressed as appropriate within the management plan.

TFOS DEWS II recommends using one of two validated questionnaires for evaluating the symptoms component of a dry eye diagnosis: the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and the five-item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). One or other should be chosen, noting the appropriate cut-off for a positive score for each. Adopting the same questionnaire within any one practice is advisable to facilitate monitoring even if the patient sees a different practitioner. The symptom recording, like the triaging and risk factor assessment, can be undertaken prior to attendance but is ideally completed in the waiting room immediately before consultation as symptoms are best recorded on the same day as the clinical signs are evaluated.

Clinical testing

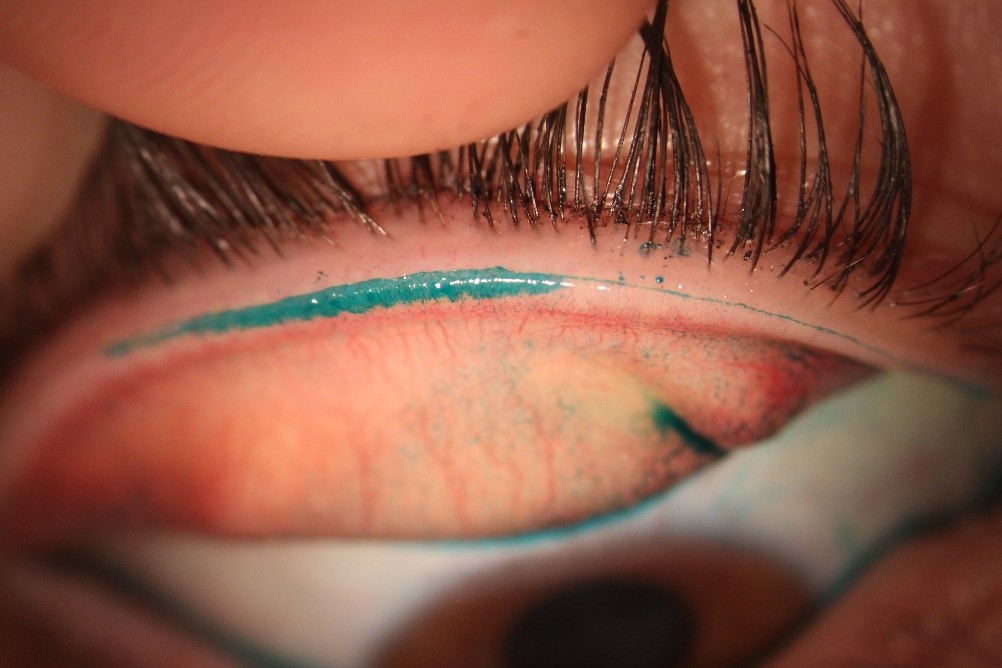

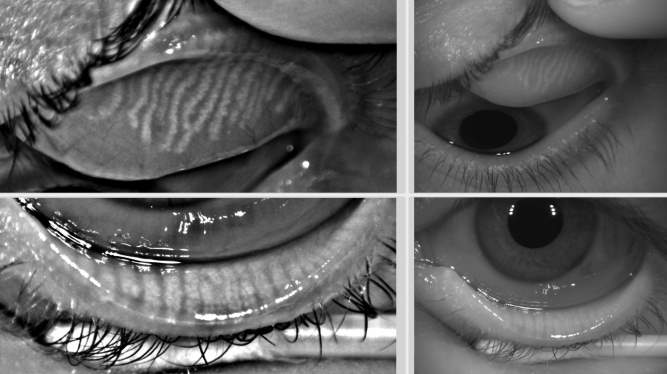

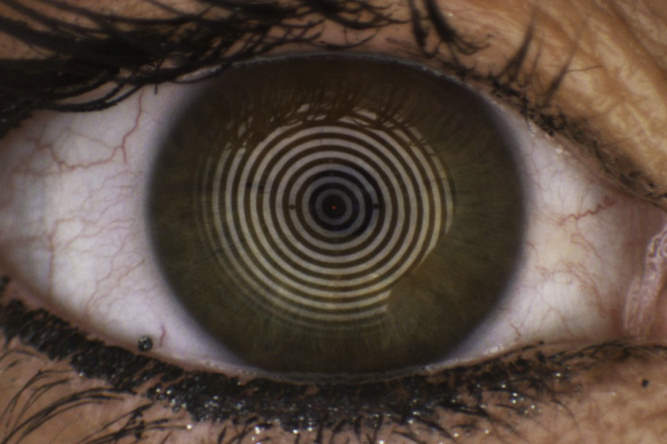

Dry eye can be diagnosed with instrumentation ranging from the slit lamp that’s available in every clinical practice, through to complex standalone equipment such as the Keratograph 5M (Oculus) or TearScience Lipiview II (Johnson & Johnson). A variety of other standalone devices and slit-lamp-mounted instruments offer diagnostic capabilities somewhere in between. The instrumentation available for clinical testing in any individual practice will dictate the order in which testing should be performed. Tests must be conducted the same way each time, and ordered from least invasive to most invasive to minimise the effect of reflex tearing on subsequent test results.

Encompassing as many of the global tests that contribute to a diagnosis of dry eye (according to TFOS DEWS II) as possible is ideal – along with symptoms: at least one positive result from tests for tear film stability, osmolarity, and ocular surface staining is needed to make a diagnosis. Conducting additional tests for subtyping is also important as this helps confirm whether the dry eye is primarily aqueous-deficient or evaporative in nature (see Table 1).

|

Clinical parameter |

Basic testing |

Advanced testing |

|

Symptoms |

OSDI or DEQ-5 |

OSDI or DEQ-5 |

|

Global testing |

|

|

|

Subtype testing for aqueous deficiency |

Tear meniscus height (slit lamp estimate) Phenol red thread (moderately invasive) Schirmer test (useful when applied without anaesthetic only for confirming severe aqueous deficiency, as highly invasive test) |

Tear meniscus height quantified digitally from infrared imaging (IR minimises risk of reflex tearing) |

|

Subtype testing for evaporative dry eye |

|

|

Table 1. Standard and advanced tests for DED diagnosis

The move towards more non-invasive and objective testing of the tear film may mean well-trained ancillary staff could perform (although not interpret) parts of the assessment, rather than the clinician themselves. Interpretation of the combined set of results (the more tests, the better) by the clinician should be used to inform the patient’s tailored management strategy.

Management strategies

Consideration must be given to the treatments and recommendations that will be offered to patients who are diagnosed with dry eye disease (DED). Artificial tear supplements remain the mainstay of treatment, but therapies that address both evaporative as well as aqueous-deficient subtypes of dry eye need to be considered (see other articles in this feature). This may involve stocking lipid supplements, lid hygiene products, including those that tackle Demodex infestation, and microwaveable wheat or bead bags for warm compress therapy, through to offering punctal plugging for aqueous deficiency or advanced treatments such as IPL (intense pulsed light) therapy and LipiFlow for evaporative dry eye associated with meibomian gland dysfunction. Offering other in-practice therapies such as BlephEx to remove crusting associated with anterior blepharitis (see article, p29), diluted tea tree oil application for Demodex eradication (see Eye on Ophthalmology, overleaf), lid margin debridement to manage excess lid margin keratinisation and therapeutic gland expression to relieve meibomian gland blockage might also be considered.

Eye care professionals are assuming greater responsibility than ever in addressing their patients’ needs through more targeted management of dry eye. Whether in a specialist practice offering a dedicated ‘Dry Eye Clinic’ or in a general practice, the commitment to following consensus recommendations in diagnosing and managing dry eye will offer consistency to patients and help advance our understanding of the disease. This, in turn, will improve the care we can offer to the increasing number of affected patients. Recognising risks and limitations in dry eye and ocular surface disease management, however, remains critical. Patients with significant corneal involvement continue to require ophthalmological review and those with a neuropathic component to their ocular surface condition might benefit from referral to a pain clinic for the most appropriate care, so having suitable referral options for particularly complex cases is advisable.

Reference

Wolffsohn JS et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf 2017; 15(3): 539-74.

About the author

Associate Professor Jennifer Craig is head of the Ocular Surface Laboratory at the University of Auckland, vice-chair of TFOS DEWS II and clinical editor of NZ Optics’ annual special feature on dry eye.