The trouble with treating VIP patients

‘VIP syndrome’ is a term used to describe the special treatment afforded VIPs. Throughout our careers, as ophthalmologists and optometrists, we will encounter a variety of patients who are considered a ‘very important person’. This could be a television or radio personality, an athlete, musician, political leader or even an esteemed medical colleague.

In a medical setting, considerable effort is made to treat all patients equally, without prejudice or influence. We sometimes exhibit strong emotions – excitement, intimidation – that must not influence our usual standard of care. But can an unconscious bias modify the treatment plan? Are we all at risk of being subconsciously duped by VIP syndrome?

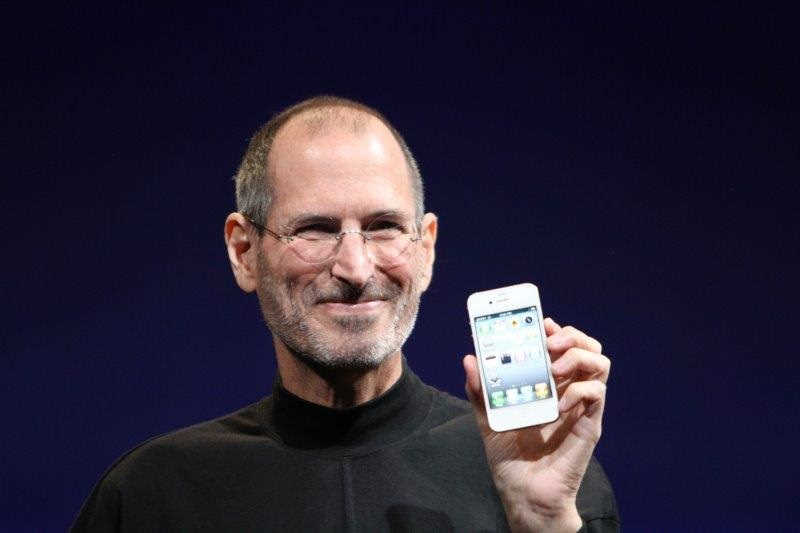

Dr Walter Weintraub, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland Medical School in the US, first described VIP syndrome in 1964 following some research he’d conducted investigating the management of 12 VIP patients¹. Ten of those VIP patients were complete therapeutic treatment failures; a number left the hospital against advice and two committed suicide. Since this research, the connection of poor medical decision-making to a patient’s VIP status has been implied in the deaths of Michael Jackson, Prince, Steve Jobs and others, with many commentators noting that any deviation from standard care can result in unforeseen misfortune. Los Angeles Times opinion columnist Jonah Goldberg referred to it in a 2020 column asking if former US president Donald Trump was getting the medical advice he wanted for Covid-19, rather than the advice he needed². “My friend Charles Krauthammer, a psychiatrist-turned-Pulitzer-winning political commentator, told me that the quality of healthcare you receive (in the US) tends to rise in tandem with your income… For some people, the two lines separate when they get so rich, they can afford the diagnoses and treatments they want, rather than the ones they need,” wrote Goldberg.

Michael Jackson

In an earlier article, making a similar point, The Guardian columnist Rory Carroll quoted US physician Dr David Agus, professor of medicine and engineering at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine and one of the cancer specialists who treated Steve Jobs³. Dr Agus told Carroll the Apple co-founder “bombarded” him with unorthodox remedies, all of which he rejected. But he said he believed some doctors could sometimes be persuaded to provide things that made no sense, such as growth hormones to make someone look younger. “The challenge is to stand up to people,” he said. “My medical practice is about tough love. It’s very data driven. Steve fired me a hundred times and he’d call me back an hour later.”

Professor Christopher Starr, associate professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York has treated many VIP patients. “The syndrome is real, but we all try not to let it change our medical decision-making or management of the patient,” he said. “Take caution when treating VIPs and make sure that your delivery of healthcare to the VIP patient is no different from your delivery of healthcare to any other patient.”

Earlier this year, UK prime minister Boris Johnson publicly thanked New Zealand nurse Jenny McGee for her care when he was ill with Covid-19, crediting McGee and a colleague with saving his life during his darkest time. McGee revealed the toughest part in caring for Johnson was the intense media presence. It is easy to imagine that media scrutiny combined with the prestigious profile of a patient can introduce treatment challenges.

Closer to home, when asked about this phenomenon and the issues it may cause, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) issued an official statement, attributed to RANZCO president Professor Nitin Verma. “As the leaders in collaborative eye care across Australia and New Zealand, RANZCO sets and maintains the standards of best patient care. Ophthalmologists must ensure all patients are afforded the same high levels of clinical, professional and culturally safe care. It is unethical to treat patients differently due their status or perceived status as VIPs.”

Richard Johnson, a clinical optometrist with the Auckland District Health Board, said he’s seen some ‘celebrity’ patients. “Most have been Kiwis, so they are very down to earth and don't expect any additional treatment over anyone else.” In New Zealand, the patient is always seen based on their triage level, regardless of their perceived importance, he added.

Senior Auckland-based ophthalmologist Dr Peter Hadden admitted he’d not heard the term ‘VIP syndrome’ before. “At least not named as such. But I do think that it is easy to unconsciously or consciously treat VIPs in a different manner. I have had the pleasure of treating a few very well-known people over the years and usually they are pleasant and approachable, which does help you forget who they are so you can get on with the job.”

Dr Hadden recommended having an action plan, aligned with your regular management protocol, which you do not deviate from. That way, even when emotions become involved you maintain ethical and professional standards.

Similarly, Professor Charles McGhee, chair and head of ophthalmology at the University of Auckland, had not heard of VIP syndrome, but also said he believed in New Zealand all patients from widely differing backgrounds are treated with the same professionalism and timing. “I genuinely believe this is not an issue that I have ever encountered in Aotearoa/New Zealand, perhaps because it is a more egalitarian society than most.”

So, although evidence of VIP syndrome can be found in both the mainstream and in clinical literature, it does not seem to be making its presence felt within ophthalmology in New Zealand. Consensus supports continuation of your regular treatment strategy regardless of patient status; suppressing any unconscious bias when examining a ‘very important person’ will set the precedent for a professional and ethical management strategy.

With additional reporting by Lesley Springall

|

References |

- Weintraub W. 'The VIP syndrome: a clinical study in hospital psychiatry.’ J Nerv Ment Dis 1964; 138:181-93

- https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-10-05/president-trump-covid-coronavirus-doctors-advice-vip-syndrome

- https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jun/17/vip-syndrome-doctors-prince-michael-jackson-elvis

Louise Wood is a therapeutically qualified optometrist working at City Eye Specialists in Auckland, New Zealand, and a regular contributor to NZ Optics.