Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) is a disorder most commonly seen in association with autoimmune thyroid disease and it is characterised by orbital inflammation leading to cicatricial soft-tissue changes. The majority of patients present with mild disease but 5% of cases suffer debilitating functional and cosmetic defects that adversely affect their quality of life.

Despite advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology, a specific therapy for TAO has been elusive. However, recent progress has been made defining the use of established treatments such as immunosuppressive agents (GCs and azathioprine) and elucidating the role of newer “biologic” agents such as rituximab and teprotumumab.

Epidemiology

TAO occurs in approximately 40% of patients with Graves’ hyperthyroidism1. The condition in its mild form is more common in women but men tend to have more severe disease. Cigarette smoking is the strongest modifiable risk factor for TAO with smokers experiencing a seven-fold increased risk for worsened diplopia. Restoration of euthyroidism is associated with improvement of TAO2. Radio-iodine therapy for hyperthyroidism is another risk-factor and prophylactic steroid therapy is usually recommended for patients with TAO who undergo this treatment and have high risk for progression of orbitopathy3.

Clinical features

The most common initial symptom of TAO is a change in facial appearance noticed by the patient. In more than 70% of patients this is due to eyelid retraction or periorbital swelling4. Other commonly-reported symptoms include photophobia, ocular discomfort, tearing and orbital ache.

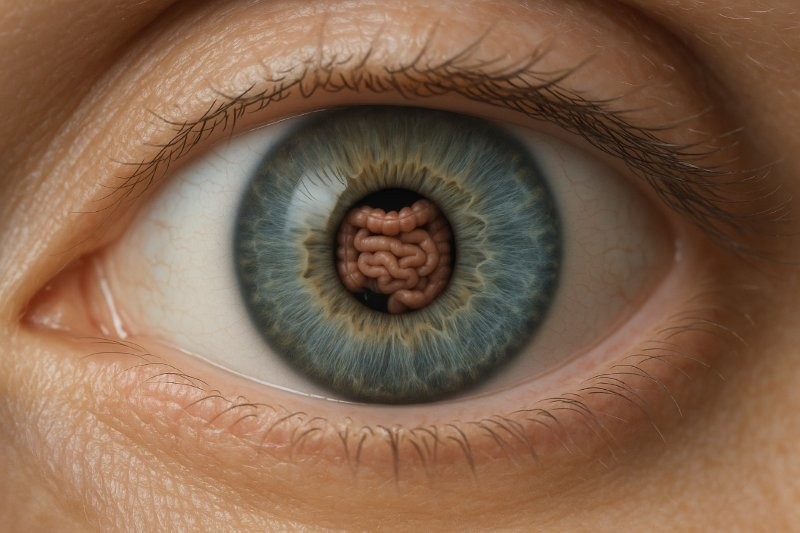

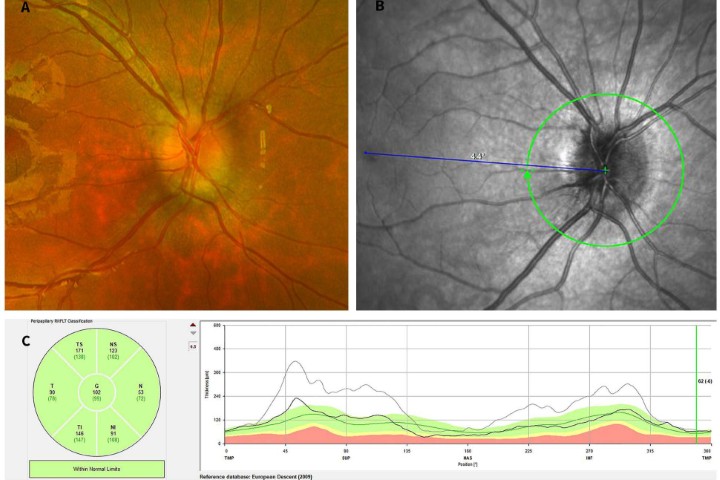

The most frequent sign is upper eyelid retraction, seen in 90% of cases (see Fig 1). Other common signs include proptosis, soft tissue swelling and eyelid/conjunctival redness. Chemosis and caruncle oedema may be observed. The signs may be bilateral or unilateral.

Fig 2. Inactive RAO with unilateral proptosis

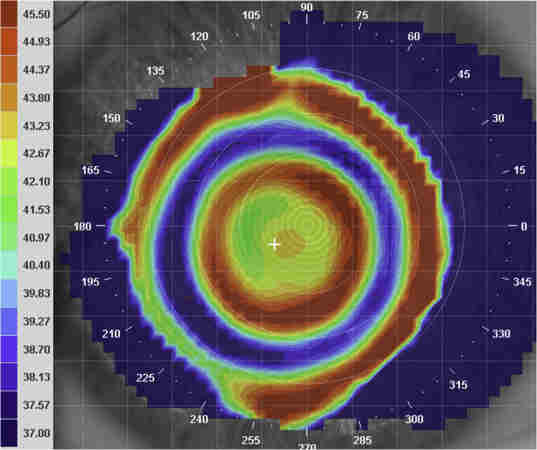

Investigations and imaging

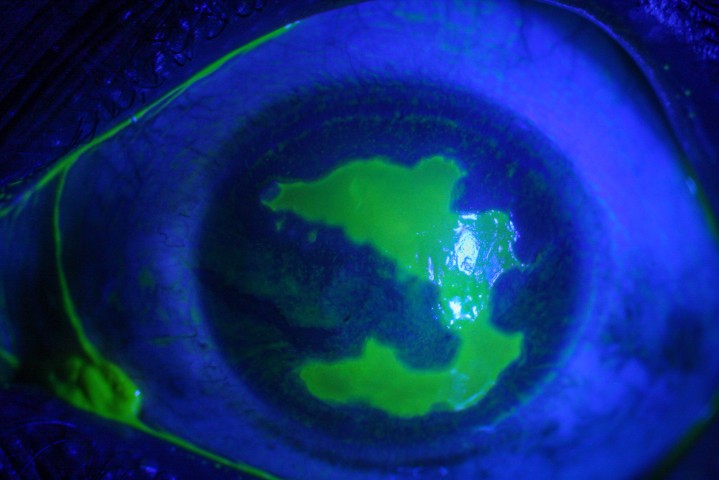

There is no definitive laboratory test to demonstrate TAO. Antibodies to the TSH receptor (TSH-R Ab) are elevated in 90% of patients with TAO, including euthyroid cases, which can be helpful as those cases often pose diagnostic challenges5. CT is the imaging modality of choice as it is widely-available, provides detailed assessment of orbital bony and soft-tissue anatomy.

Fig 3. Axial soft-tissue CT orbits showing enlarged EOMs and left proptosis.

MRI scan avoids radiation exposure and is helpful for assessment of disease activity: measurement of a prolonged T2 relaxation time in the extraocular muscles correlates with improved responses to anti-inflammatory treatments.

Management principles

Assessment of disease severity and activity is important in formulating a management plan for a patient with TAO.

Activity is assessed using the Clinical Activity Score (CAS): a score of ≥ 3/7 indicates active disease and correlates with success using medical immune suppression. Severity is classified as ‘mild’ for patients with TAO that has a minor impact on daily life, with < 2mm eyelid retraction or < 3mm proptosis. ‘Moderately-severe’ TAO includes more severe signs and diplopia, while ‘sight-threatening’ TAO occurs when dysthyroid optic neuropathy or corneal breakdown develops.

- Mild TAO

In most patients with mild disease supportive treatments such as advice about smoking cessation, use of sunglasses when outdoors, lubricants and control of thyroid dysfunction are sufficient. Selenium supplementation, 100𝞵g twice-daily for six months, has been demonstrated in a randomised, placebo-controlled trial to result in improved quality of life (QoL) and overall ocular involvement6.

- Moderate-severe and active TAO

High-dose systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) are the first-line therapy for moderate-severe TAO3. Intravenous therapy is more effective and has a more favourable side-effect profile compared to oral administration. Current guidelines for most patients based on a randomised controlled trial (RCT) are for a cumulative dose of 4.5g methylprednisolone, divided into 12 weekly infusions (six weeks of 0.5g followed by six weeks of 0.25g)7, with higher doses up to 7g and consecutive daily dosing reserved for severe, sight-threatening disease due to the risk of adverse events3. Patients should be screened for contra-indications, including severe hepatic dysfunction, recent viral hepatitis, cardiovascular or psychiatric morbidity and diabetes. Second-line therapies may be considered for patients unable to tolerate high-dose GCs or those with incomplete response to treatment.

- Orbital radiotherapy has been shown in RCTs to be more effective than sham radiation for patients with diplopia8,9 but a recent trial found no added benefit in ophthalmopathy index or clinical activity score (CAS) for patients receiving oral GCs when radiotherapy was added10.

- Cyclosporine when combined with oral GCs has been shown in two RCTs to be more effective than either treatment alone in patients with moderate-to-severe TAO with better ocular outcomes and decrease recurrences3.

- Rituximab (RTX) is a monoclonal antibody to the CD20 antigen expressed on B-lymphocytes. It blocks antigen presentation by the B-cell after CD20-induced lysis which leads to T-lymphocyte deactivation reducing their liberation of cytokines. Two RCTs examining RTX in TAO have been published with conflicting results. In one trial RTX was found to be superior to GCs for active disease11 but the other RCT did not find any benefit for RTX12. Both studies were small and differed with respect to disease duration, so larger RCTs are needed, but the positive result in one of the trials suggests that RTX may have a role in the management of TAO.

- Teprotumumab (TTM) is a human monoclonal IGF-1R inhibitor. It blocks induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg. TNF- α) by TSH. A double-masked, RCT assessed 88 patients with active TAO and, for the primary endpoints of >2mm proptosis reduction and >2 CAS points, found 69% response with TTM versus 20% with placebo13.

Surgery

The role of surgery in the management of TAO is principally rehabilitative and reserved for cases that have become stable either as a result of the natural history of the disease or following immunosuppressive treatment. The exception to this rule includes patients who present with sight-threatening TAO, poorly-responsive to medical treatment. These patients may require urgent orbital decompression for dysthyroid optic neuropathy (DON) or severe ocular surface exposure.

Surgical management includes orbital decompression, strabismus and eyelid surgery, including blepharoplasty. In patients with stable, inactive disease, surgical therapies aim to reduce proptosis and associated photophobia, manage diplopia and improve appearance. TAO often affects patients in early adulthood through to late middle-age and, in many cases, results in distressing morbidity. Surgery plays an important role in rehabilitation for these patients.

About the author

Dr Richard Hart is an ophthalmologist practising at City Eye Specialists and Greenlane Clinical Centre. He completed subspecialist training in oculoplastic surgery at Moorfields and Chelsea & Westminster Hospitals in London. He has published articles and textbook chapters in ophthalmic journals and books, and is a regular presenter at national and international meetings.

References

- Daumerie C Epidemiology in Wiersinga WM, Kahaly G Graves’ Orbitopathy 2ed 2010 Basel. Karger 33-39

- Prummel M et al Acta Endocrinol (Copenhagen) 1989; 121(Suppl2):185-189

- Bartelena L et al Eur Thyroid J 2016;5:9-26

- Dickinson AJ Clinical Manifestations in: Wiersinga WM, Kahaly G Graves’ Orbitopathy 2ed 2010 Basel. Karger 1-25

- Gerding MN et al Clin Endocrinol 2000;52:267-271

- Marcocci C et al N Engl J Med 2011;364:1920-1931

- Kahaly G et al J Clin Endocr Metab 2005;90:5234-5240

- Mourits M et al Lancet 2000;355:1505-1509

- Prummel MF et al J Clin Endocr Metab 2004;89:15-20

- Rajendrum R et al Lancet 2018;6:299-309

- Salvi M et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:422-431

- Stan M et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:432-441

- Smith T et al N Engl J Med 2017;376(18):1748-1761