Don’t stop till you get enough

The conventional idea of retirement is to stop work at age 65 and put your feet up at home. But for many eyecare professionals, it seems that’s an outdated concept. By Cait Sykes.

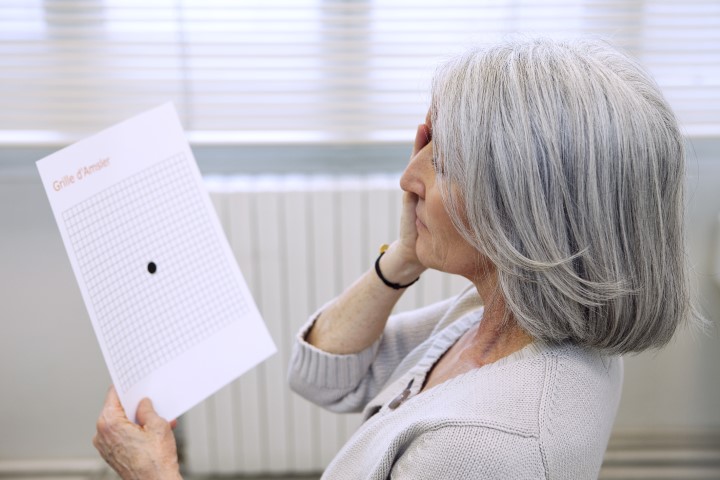

At the end of the week he chats to NZ Optics for this story, Paul Rose CNZM, is heading off to the Middle East and Europe. But the trip is for business, not pleasure; he’s embarking on a five-week lecture tour.

It’s not an uncommon occurrence for the inventor of the Rose K lens, whose schedule has typically seen him lecturing offshore for three months a year. Rose describes his working life today as about “80% full-time”, with his contract consulting work for Japanese company Menicon (which bought the company he co-founded, Rose K International, in 2008) consuming most of that. However, he’s also still developing new products and is a 50% owner of Hamilton-based optometry practice, Total Vision.

Despite ‘retiring’ from practising optometry, nine-to-five, around eight years ago, Rose says there are many factors that have allowed him to maintain a dynamic working life despite being a handful of years beyond the conventional age of retirement.

Opportunity is one, through the likes of his work with Menicon. Technology, which increasingly facilitates more mobile and flexible working arrangements, is another. Good mental and physical health also play their role.

Paul Rose

An active retirement: the new norm?

But Rose asserts he’s not an anomaly when it comes to eschewing the conventional idea of retirement – that you stop work and put your feet up at age 65.

“I think today’s 70 is the new 60,” says Rose. “Today you don’t consider yourself ‘old’ at 70 if you still have your physical and mental wellbeing, so you tend not to consider retirement. We have this huge number of older people coming through who can still contribute a lot to the workforce and, yes, there may be financial reasons for that, but it’s also a reflection of people's health and their attitudes to old age.”

Statistics back up Rose’s observations. In 2016 around 24% of New Zealanders aged 65 and over were working either full or part-time. And for those aged between 65 and 69 years, that figure rose to 43%.

David Boyle, general manager of education at the Commission for Financial Capability, says that latter figure is high relative to other countries and is perhaps influenced by the fact New Zealanders aged 65-plus can access NZ Super whether they’re working or not.

But ultimately, as Rose intimates, greater longevity is driving the changes we’re seeing around the ageing population’s increasing participation in the workforce.

“Personally I’m not a fan of the word ‘retirement’,” says Boyle. “When you look that up in the dictionary it basically says that’s when you stop; when you stop work, when you stop earning an income. And as those statistics show, New Zealanders increasingly aren’t doing that for a whole lot of reasons – and not just because they have to.”

Boyle points to the findings of a survey carried out by the Commission that canvassed around 3,500 people aged over 65 about their participation in the workforce, including what motivated them to work.

About 54% said they had to keep working for financial reasons, but the remaining 46% cited other reasons, such as gaining a sense of purpose, contributing to the community, being socially connected and passing on knowledge and expertise to the next working generation.

The survey also found, however, that older New Zealanders had some fears they wouldn’t be able to enjoy their later years if they had to keep working to the extent they had been.

“Something more and more New Zealanders are thinking about is how to have flexibility so they can enjoy their later years but also still contribute and make a little bit of money along the way. It can be a difficult transition, which is why it’s so crucial for people to start jotting down a plan about what’s important to them, both career-wise and personally.”

For many, striking that balance comes by taking an incremental approach to the transition into retirement.

Avoiding retirement “death”

Retired optometrist Hywel Bowen learnt some early lessons on how not to approach retirement when he began practising in Thames, the town he’s called home for 39 years.

“When I first came here I noticed that a lot of retired farmers would move into town and go from working 80 hours a week to nothing. Then six months later they’d be dead. That really struck me and I’ve always been aware of that danger.”

Bowen was 52 when he sold his busy practice, which typically saw him working 55-hour-plus weeks. He then worked as a locum for three years in different locations around the country, and a further three in Thames. Originally full-time, he dropped down to four days a week, then to three once working back in Thames, before retiring around 18 months ago.

“Mentally, working for someone else is not so exhausting. And working part-time gives you time to develop other interests and a broader social base in the community you live in.”

Bowen describes a life that’s always been active: he spent six years on the New Zealand Association of Optometrists (NZAO) Council, five years on the Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians Board (ODOB), lectured intermittently at university, and has done 19 trips with Volunteer Ophthalmic Services Overseas (VOSO) - his first in 1984. He’s also a former VOSO chair and secretary, and remains a trustee. In his local community, he’s been involved with schools and Scouts, and he’s been a Rotary member for the past 14 years and is currently secretary of his club.

So even in his retirement proper, there seems little inclination to put his feet up.

“In terms of interests, family is the main thing: I’ve got three kids and four grandkids now. I keep fit with tramping and cycling. Last year I did ‘Tour Aotearoa’, where you bikepack from Cape Reinga to Bluff, and I’m doing it again next year. It’s 3,200km, and over that distance I climbed the equivalent of Mt Everest 3.3 times – there are a lot of hills in New Zealand.”

Mike Firmston first ‘semi-retired’ more than 20 years ago, when he and his brother-in-law and business partner Bryan Matthews sold their Optique Eyewear chain to OPSM in 1995. In the ensuing five years, however, Firmston ended up working in the corporate world for OPSM, gaining experience and insights he likens to doing an MBA. So when Matthews came knocking with an idea for a new business, Specs Direct, he jumped at the chance to put that business experience to work in another venture, and any further retirement plans went on hold.

It was just over a year ago, at age 70, that Firmston really retired, when he and Matthews sold their business to a senior optometrist who’d been working in their firm for about 20 years.

Firmston too has had a busy professional life, including nine years on the board of ODOB and as a director of training organisation Opti-Blocks– a role he still holds. He also continues to be involved in optical wholesale company Tranz Optics, which he co-owns with Matthews.

“When I was young and the children were growing up it was my wife that carried the burden of bringing up the family. I’d arrive home in the evening and just be able to get them in the bath and read a story then you’re off fairly early in the morning again. All those years I felt like I wanted to invest more in family time,” explains Firmston.

“But I thought the looming challenge for me with retirement would be the balancing act, because I knew I wouldn’t just be able to put my feet up.”

David Boyle

Finding time for smaller joys

Firmston admits he’s thoroughly enjoying retirement: spending time and helping out with their five children and nine grandchildren, and doing a bit of domestic and international travel. He also does some volunteer work and has a long list of other groups he’d like to contribute to.

“There are all those things you’ve been associated with in a small way in your life, and I had this list of things I’d maybe like to do when I retired. But I thought to myself, the challenge is going to be having the time to be able to do all those things and still have the flexibility I want.”

Like Firmston, Rob Allan has had the transition towards retirement smoothed thanks to a business succession opportunity. In Allan’s case his son and daughter-in-law are now the owners of what was his Whangarei-based optometry practice, Lowes & Partners. But despite Allan receiving his official retirement send-off alongside last year’s annual Christmas party, he’s still working in the business. It’s a symptom of the perennial problem faced by many healthcare practice owners in provincial New Zealand – finding staff, he says.

“It was my intention to gradually reduce my hours, but really what dictates how much work I do is the staffing levels at any given time. At one point I was doing 60 hours a week. That’s not necessarily what I would wish or what the current owners would wish, but it’s what the business dictates.”

As with Bowen and Firmston, Allan is well accustomed to a busy professional life. During his first 20 years in practice in Scotland, he represented his fellow optometrists at local association level, the Scotland-wide level and nationally, as part of the Association of Optometrists’ Council. In New Zealand, where he’s practised for 30 years, he’s been a member of the NZAO Council.

Allan is currently working part-time until a replacement can be found for a staff member who left mid-year. Once that happens, however, he still anticipates continuing his work in the business mentoring staff on specialist contact lens work, although, he adds with a smile, “I have been playing a lot more golf”.

Plan for the unexpected

Stu Allan (no relation) is founder of practice support consultancy OpticsNZ and says some of the best examples he’s seen of successful transitions into retirement are when the practitioner continues to work in the business once they’ve sold it, either as an employee or consultant.

“A gradual departure from the business establishes a win-win outcome,” says Allan. “The new owner is able to leverage the goodwill and have a mentor to call upon; the retiree is able to slowly exit the profession with respect and dignity.”

However Allan says there are a range of factors that may make it more challenging for practice owners to sell their operations today than in the past. In particular, much greater competition in optometry makes it harder to realise financial returns, while advances in technology bring with them increased demands for capital investment, he says.

“There are some practice owners that are on the front foot and really well planned. They have all the financial information to take a practice to market, and the really switched-on ones realise they do want to step away from the emotional commitment and sell something they’ve built up, in some cases over 30 to 40 years.”

However, those who haven’t planned well can find themselves in a tight spot, for example if they have to sell fast due to poor health, he says, while another challenge of transitioning out of working life, is the potential emotional and social disconnection that can occur.

Allan’s not alone in his observation. Given eyecare professionals work so closely with people and make tangible differences to their lives, many spoken to for this story talked about the importance of maintaining that sense of social connection and contribution to the community during the transition into retirement and beyond.

Retiring when you’re ready

Esteemed ophthalmologist Associate Professor Bruce Hadden CNZM retired from surgery at age 67 and worked a further four years as a consultant. Then at the urging of University of Auckland ophthalmology chair, Professor Charles McGhee, A/Prof Hadden went on to write a book on the history of ophthalmology in New Zealand and complete a Doctorate in Medicine, alongside teaching optometry and medical students (the latter he still does as needed).

But A/Prof Hadden is about to depart for Europe when he chats to NZ Optics, with plans to spend a week walking in Ireland, then on to London and then to spend time with family in Switzerland. Hadden characterises himself as almost fully retired now, and says although he’s happy at this stage in his life he’s not as fulfilled as he was in the prime of his career.

“There’s no question that you miss the feeling of fulfilment that one gets from contributing to people, contributing to society, contributing to ophthalmology and its organisation, contributing to the College (RANZCO) and ensuring the next generation is adequately educated for their responsibilities. I would advise people to think long and hard about that and not to retire before they need to because once you’ve done it you can’t turn the clock back.”

Despite “not being able to hit a golf ball to save myself”, Hadden has jogged all his life and these days also catches up for coffee with a group of like-minded locals four days a week, who regularly gather for cycling expeditions as well.

“What becomes more and more important as you have less and less to do is to maintain your friendships with many people and keep active. If you don’t use it, you lose it – and that applies to your brain and your body.”