More able canes

According to Perkins School for the Blind, the oldest school for the blind in the US, in 1921, having lost his sight in an accident, James Biggs painted his walking stick white to make it more visible to the cars driving near his home. The idea spread globally over the next decade or so. But, aside from making it from lighter materials such as aluminium, fibreglass or carbon fibre, that was the white cane’s last update for nearly a century.

However, a flurry of recent interest has led to researchers in the US, UK and India independently developing ‘smart canes’ that use GPS, light detection and ranging (lidar) and a host of sensors they all claim will increase independence for white-cane users.

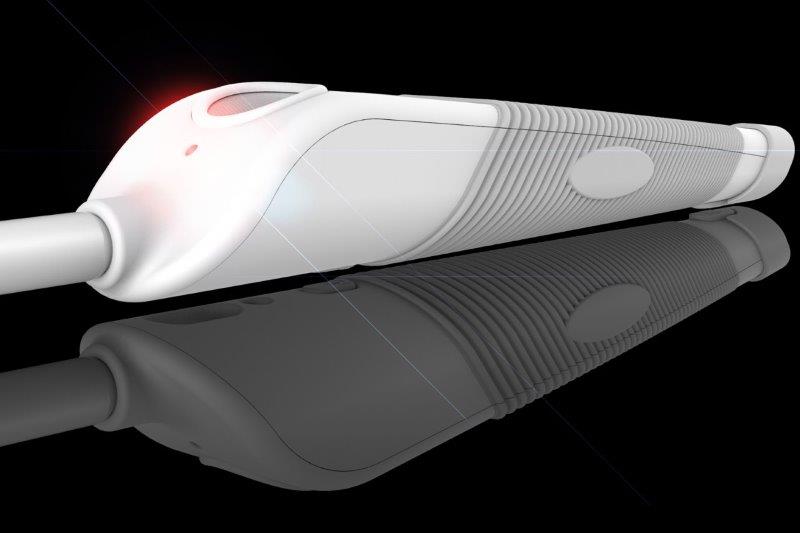

Already on the market is WeWalk, which boasts several awards, including Time Magazine’s Best Invention 2021. For about NZ$850, users can attach the WeWalk handle to the top of any cane to detect obstacles above waist height, which the company says will help the visually impaired maintain social distancing and avoid low tree branches, for example. A speaker on the handle delivers verbal directions in response to verbal commands from the user. When paired with a smartphone, WeWalk’s developers say it will guide the user to bus stops, restaurants and shops, while a touchpad on the cane means the user’s phone can stay in their pocket while navigating.

The WeWalk handle

Blind Low Vision New Zealand (BLVNZ) was sent a WeWalk cane to test, said BLVNZ’s national technology advisor Thomas Bryan. “Many people enjoy WeWalk but it is not everyone’s cup of tea, just like a guide dog isn’t everyone’s preferred mobility option. Many of the new smart canes require a smartphone, which many of our clients don’t have, and if they do, they may not be able to afford data or the cost of the cane.”

In the US, Stanford University’s Augmented Cane has a motorised wheel in contact with the ground, which tugs or nudges the user away from hazards and towards their destination. A study of the cane, published in Science Robotics in October 2021, showed users’ average walking speed increased by 18% compared with using a standard folding cane. Crucially, researchers made the cane’s software, parts list and assembly instructions free to download, keeping the total cost of the device to around $560.

The road ahead

Blind runner Thomas Panek ran 5km in Central Park, New York, with Project Guideline

Still under development, Project Guideline, Google’s cane-free guidance system for runners, teams a phone’s camera with a waist-mounted harness and bone-conduction headphones (which transmit sound via vibrations on the wearer’s cheekbones, leaving the ears free of obstruction). Although the system still requires a painted or tape line on the road for guidance, in November 2020 Guiding Eyes for the Blind president and CEO Thomas Panek used it to run independently for the first time in decades, completing 5km in New York City’s Central Park.

Virginia Commonwealth University’s Lingqiu Jin tests the university's prototype cane. Credit: A/Prof Cang Ye

Meanwhile, Virginia Commonwealth University researchers, led by Associate Professor Cang Ye, have developed a cane with a visual positioning system to aid navigation. The prototype’s tracker, floor detector, camera and inertial measurement unit (which measures an object’s movement and orientation in space) provide data for the active rolling tip (ART), which, like Stanford’s Augmented Cane, ‘steers’ the user, who also receives audio guidance through a Bluetooth headset. At present, however, the system has only been tested indoors as it relies on 2D floor plans and cannot deal with moving objects, A/Prof Ye told Healio. “While we have solved the problem of locating the robotic cane in an indoor space by processing the data from camera and motion sensor, if the environment is highly dynamic, the vision-based positioning system could fail.”

Face time

The XploR cane

Taking a different tack, researchers at Birmingham City University in the UK are addressing the social aspect of blindness with a cane that recognises faces from nearly 10m away. The XploR cane technology employs facial recognition software, GPS and a camera with a 270-degree lens just below the cane’s handle to capture a broad view of the environment. The cane’s software draws on a database of photos from services such as Gmail and Outlook or from a photo taken with the cane’s camera. When a face matches one in the database, the individual’s information will be relayed to the user via a Bluetooth bone-conduction earpiece.

But Chris Danielsen, a spokesperson for the Federation of the Blind in the US, said that while a basic cane is cheap, a high-tech one could be costly. “A smartphone app that performs the same function (such as facial recognition) might be more cost-effective,” he said.

Is this what blind people want?

NZ Optics columnist Trevor Plumbly has been living with retinitis pigmentosa for 20 or so years. After reading about these high-tech white canes, he told us, “Like most blindies, I'm always up for something that will make life easier; over the years I've played around with the odd ‘breakthrough device’ without much joy. The basic problem for me is that, like a lot of senior blindies, I find the status quo a preferable option to struggling with new technology.”

Plumbly said he loves the simplicity of his current ‘tennis ball’-tipped cane, which trundles along the ground, providing ample warning of any obstacles. “The thing about the white cane is its simplicity, and most blindies love simple! I’m sure younger, tech-savvy folk will be keen to give them a go, but do I really want to depend heavily on something soldered up at home, like the Augmented Cane? Do I need to get from A to B 18% faster? I've been down Queen Street at lunchtime and I don’t think I’m up for that one!”

Former Retina NZ president, Fraser Alexander, who’s also visually impaired, said, “The question of whether the extra functions offered by such devices are what users of conventional white canes want and need, of course, will have as many answers as responders but my short answer is ‘unlikely for me for the foreseeable.’ I’d be likely to remain with the white cane travelers who are comfortable with a conventional cane augmented by familiarity with daily environments and other technology.” For Alexander, that ‘other technology’ would be Aira, a service where ‘agents’ offer assistance with visual information over the phone.

“From my experience, most emerging adaptive technology does enable blind people to achieve levels of greater independence and confidence, and smart canes are no exception. The key is committing to exploring the capabilities of the technology and developing one’s skill level, such that you can interact with it effectively,” he said, adding that if he believed a smart cane would significantly enhance his independence, he’d happily part with NZ$560 and dedicate the time to decide if the device works for him. “But what I’ve read doesn’t convince me.”