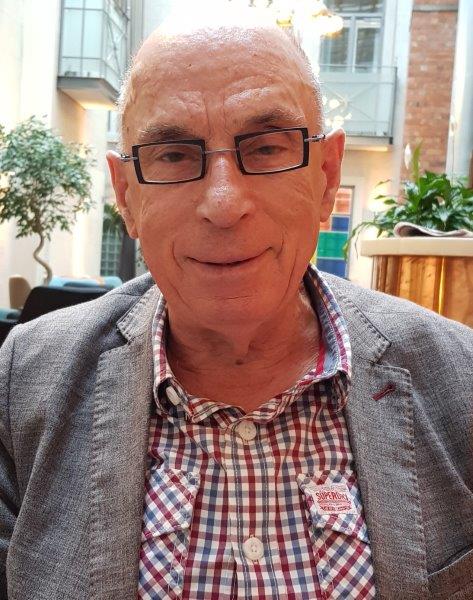

Roger Apperley: 50-plus years in focus

With a career spanning more than 50 years, including the move from senior partner at one of the biggest independent practices at the turn of century, Barry & Beale, to its corporate successor OPSM, optometrist Roger Apperley has experienced many optometry changes in New Zealand. A staunch defender of professional standards and continuing education, and a pioneer in behavioural optometry when it was at its most controversial, his former mentee and partner, low vision specialist optometrist Naomi Meltzer persuaded him to share some memories lest we forget how far optometry has come and the foundations that will always be important.

What advice would you give to a new graduate?

To be ready for change during your career, both in employment and in ownership opportunities. I have been fortunate that my career path has been in the same practice, albeit with different ownership. A career path for life is no longer the norm. With decreasing ownership prospects, a young person with a desire for self-determination is unlikely to be attracted to the profession. This is leading to a new generation seeing themselves as technicians rather than primary healthcare practitioners.

How did you manage the transition from a senior partner in an independent practice to an employee of a new, multinational chain?

Initially it was quite seamless as the management at the time allowed us to continue the mode of practice we were used to. So, other than some limitations on our ability to use our long-established preferred suppliers, the practice was relatively unchanged and we enjoyed concentrating on our professional responsibilities rather than practice management.

Over time – particularly when management changed and was led more by experienced businesspeople without much prior knowledge of optometry – it became more difficult, however, to always provide complete vision care relating to more complex contact lens patients, such as rigid gas permeable (RGP) wearers. We were no longer given the space, time or trained assistants to provide those services in-house. I have never been told what I can or can’t do, though, except for the need to have more compressed examination times and, if required, to reschedule a patient for additional diagnostic tests, though that is sometimes difficult, particularly for elderly patients who may have travelled a considerable distance for the appointment. Positively, however, has been the ability to use new technology as it’s become available, such as ultra-widefield digital retinal scanning and optical coherence tomography.

Roger Apperley

What is a highlight of your career…

I have enjoyed the stability and also the ability to travel to overseas conferences and participate in some of the changes, especially in education.

…and a low point?

The fact that although we were on a path of fee-for-service, now, regrettably, we have regressed to being purveyors of merchandise to earn an income.

What has been the biggest advance in eyecare over your career?

Several years after my graduation with a diploma of optometry, this was changed to a bachelor’s degree. That made a significant change to patients’ and our own perception of the profession as having improved standards of education and continuing professional development.

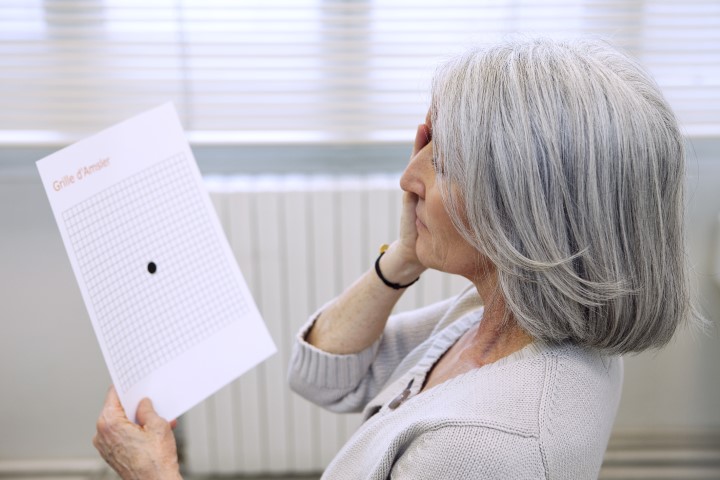

The use of diagnostic pharmaceutical agents, particularly for dilation, increased our ability to diagnose. That, combined with instrumentation such as tonometers, eased our measurement of intraocular pressures, while retinal photography and automated retinal field screening instruments augmented our ability to detect and monitor change. Multifocal lens designs and new lens materials and coatings also made a significant improvement in patient satisfaction. While another major advancement was the use of small-incision cataract surgery and intraocular lenses. Anyone old enough to recall the misery of fitting patients with lenticular lenses post-cataract surgery would surely agree.

What has changed between optometry and ophthalmology?

I recall as recently as the 50th annual NZAO conference (1980) being forcefully told by a highly respected speaker to not offer a prognosis, not to diagnose and certainly not to treat any ocular condition; treatment of any eye condition, such as dry eye, was frowned upon and repercussions could follow.

With therapeutics training and certification, optometrists can now manage many ocular conditions. Our ability to dilate has unfettered us from the constraints that ophthalmology had put on us and with this ability to detect pathology, we are now able to give more timely and appropriate referrals, which benefits everyone.

This is such a far cry from the time when optometrists were censured for even mentioning cataracts to patients. Now the relationship is generally good, and I have a number of colleagues working in conjunction with ophthalmologists. I do worry, however, that the drive towards optometrists taking on more of a trained technician role potentially leads to optometry no longer being a standalone profession.

As a long-term, active supporter of NZAO, how do you see its role now in the future of optometry?

It should be at the centre of advancing the influence of what optometry has to offer, especially relating to publicly funded vision care. Unfortunately, however, there is very little representation from those in corporate employment, which is now a large portion of the profession. Therefore NZAO is no longer a widely representative body. This is regrettable, in terms of optometry’s future professional standing.

You were my mentor, helping me to be accepted as a female partner in a traditionally male-dominated profession. Who was your mentor?

Peter Barry, a man of remarkable foresight. He introduced the succession plan whereby new graduates such as me could enter a collegially based practice with encouragement to develop subspecialities. He was ahead of his time in proposing ideas like joining international optometric bodies such as the World Council of Optometry and American Academy of Optometry.

Why is being a mentor so important?

To pass on experience, which is equally a two-way exercise since the mentor becomes more up to date on clinical knowledge. It also gives new graduates a better appreciation of real-world practice and enhances their professional development.

What is the skill set of today’s graduates compared with, say, 20 years ago?

Today’s grads are extremely knowledgeable, especially in the medical aspects of eyecare, which has significantly enhanced our professional standing and the scope of eyecare we provide. I do sense with alarm the lack of importance placed on accurate subjective refraction, especially including a proper binocular assessment. There is also a reluctance to fully appreciate the information that skills like retinoscopy can provide – instead of being reliant on auto-refraction – regrettably, this includes not recording these findings and the important correlation between objective and subjective results. Our raison d’etre is to provide clear, comfortable binocular vision and to view subjective refraction as the pathway to this, so this is where mentoring can be important.

How and why did you become involved in behavioural optometry?

I was encouraged to take an interest in children’s vision and being a new parent at the time, I felt a natural affinity with visual development in children. Much of the rationale of vision therapy was, for many in the profession and certainly in ophthalmology, highly questionable as were the outcomes claimed by these methods. It took some fortitude to recommend behavioural vision care to parents in the face of contrary advice from other professionals and resulted in my having to defend myself before a disciplinary hearing.

Thankfully this is now a recognised field of vision care and rehabilitation and, as a result, countless past and future generations of New Zealanders have and will have the ability to achieve their full potential.

You have always enjoyed a rather avant-garde choice in spectacle frames yourself, what do you think of current fashion trends?

How many cycles of fashion trends can one experience in one’s career! Although in later years I’ve been less involved in assisting patients in frame selections and procuring new styles, I find that providing patients with optimal functioning visual aids continues to be challenging and satisfying.

To paraphrase Dickens, my time in optometry has seen the best and the worst, some wisdom and much foolishness, but overall I can say that optometry has been immensely rewarding and fulfilling.