A closer look at submacular haemorrhages

Submacular haemorrhage (SMH) is a vision-threatening complication most often seen in neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). Other causes include choroidal neovascular membranes secondary to pathological myopia; choroiditis; angioid streaks or choroidal rupture; retinal artery macro-aneurysm; and idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV).

SMHs are rare events, with incidence reported as 5 million/year in a Scottish population-based surveillance study1. A Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB) Registry study of those receiving anti-VEGF treatments for nAMD showed an incidence of SMH with vision loss to be 4.6 per 1,000 patients/year, making it relatively common in an advanced AMD popluation2. Risk factors include male sex, systemic hypertension and use of anticoagulant medications such as warfarin, dabigatran or rivaroxaban, plus anti-platelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel2,3. IPCV is particularly associated with larger or recurrent haemorrhage2.

Submacular haemorrhage is toxic to retinal photoreceptors via three mechanisms in an animal model3:

- Hypoxia: the haemorrhage physically separates photoreceptors from choriocapillaris, impairing diffusion of oxygen and nutrients.

- Mechanical traction: fibrin contraction within the clot can shear photoreceptor outer segments.

- Iron toxicity: iron in blood leads to free radical formation that induce oxidative damage.

The natural history of submacular haemorrhage is very poor, with almost 90% of patients having vision worse than 6/60 at 24 months follow up4 and optometrists are often the first point of contact for patients with sudden loss of vision.

Here we present guidelines for the assessment and management of patients with submacular haemorrhage.

Assessment

Most patients presenting to their optometrist or seeking medical attention would have noticed a change in vision. Assessment begins with a comprehensive history and examination. The focus of the history should be on the timing of onset of the visual loss to determine duration, with attention to medical and ocular history and systemic medications, particularly those affecting clotting.

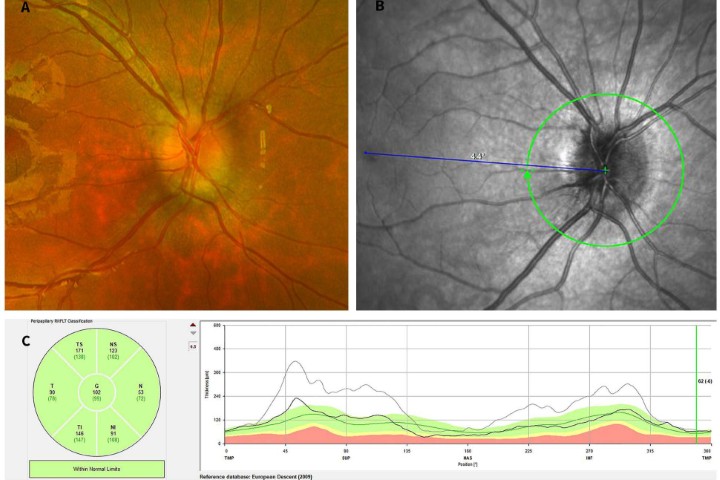

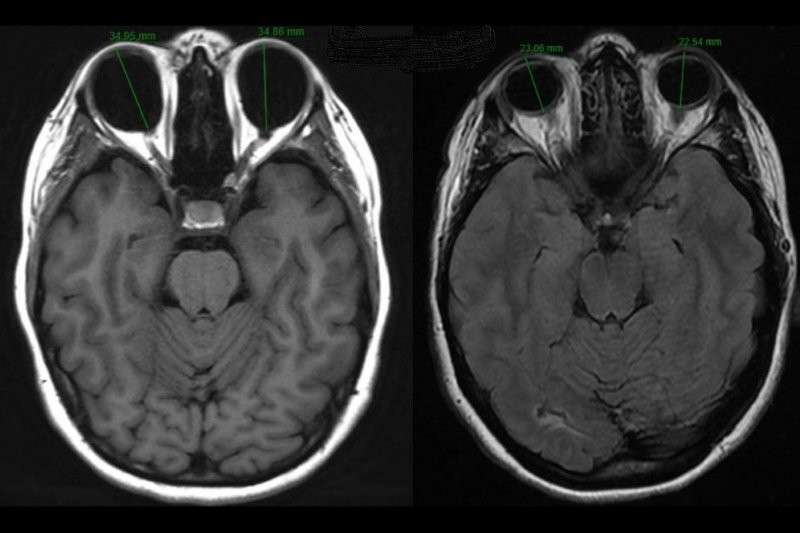

Examination should include visual acuity, intraocular pressure measurement, slit-lamp examination and fundoscopy to determine the extent and location of the haemorrhage (presence of vitreous, pre-retinal, intraretinal, subretinal, sub-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) haemorrhage). For imaging, optical coherence tomography (OCT) is mandatory to determine whether the bleed is subretinal or sub-RPE, which will affect management decisions. Colour fundus photos can also assist in differentiating the anatomical layers – pre-retinal haemorrhage will obscure retinal vasculature, whilst subretinal haemorrhage has a lighter colour than sub-RPE bleed.

Prompt referral to local ophthalmology services is essential.

Management

There is no single consensus on the best treatment for SMH and the management is guided by duration, location and the size of the haemorrhage, as well as patient factors. The heterogenous nature of SMH presentation makes well-designed randomised controlled trials difficult to conduct, so management recommendations are based on low-level evidence, consensus and individual professional opinion.

Management options range from conservative monitoring to clinic procedures and surgery. Acute referral to the closest ophthalmology service is recommended for further discussion and management and the following general treatments are normally recommended:

1. Observation

In certain circumstances, observation may be appropriate for incidental or chronic cases where SMH has already organised into a disciform macular scar. It may also be an option for very frail patients, those with advanced dementia in care settings, or those with low visual demand and long history of symptoms, after discussion with the patient and family.

2. Intravitreal anti-VEGF monotherapy

For a small or thin SMH, intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) medications such as bevacizumab (Avastin) might be sufficient. This represents current first-line therapy for choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) from nAMD in New Zealand.

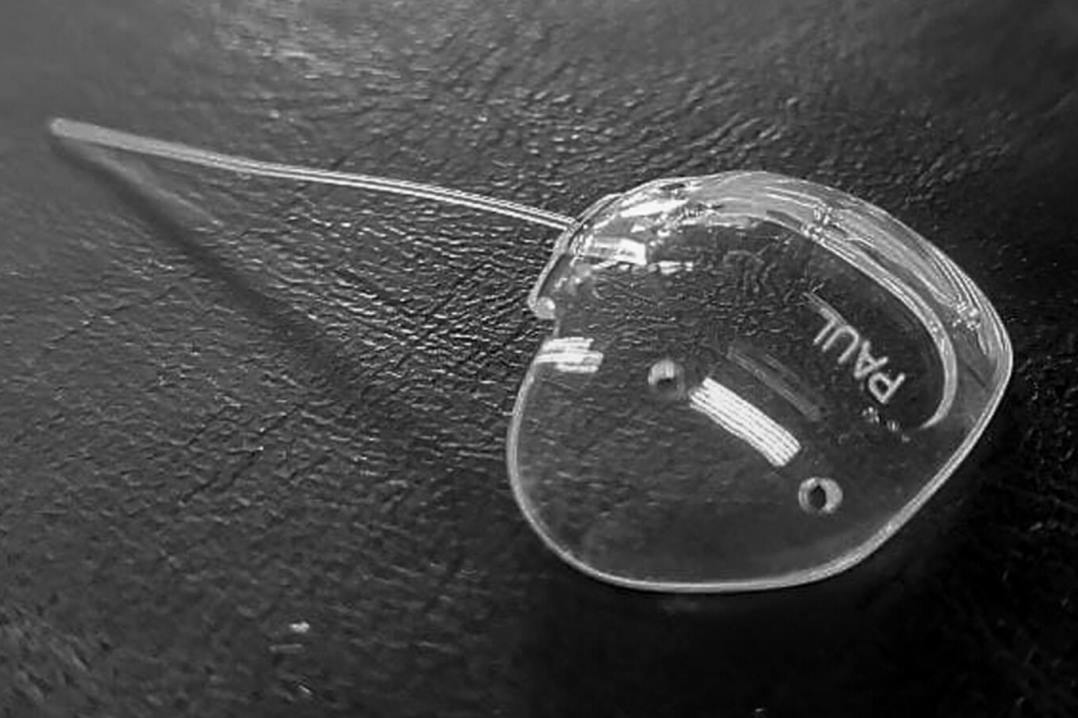

3. Pneumatic displacement using intravitreal anti-VEGF, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and gas

Pneumatic displacement of submacular haemorrhage away from the fovea was described by Heriot in 19965. It involves lysing the submacular haemorrhage clot with intravitreal injection of tPA (eg. alteplase) and 0.3-0.5ml of expansile gas (typically 100% SF6 or C3F8) to ‘push’ the haemorrhage away from fovea. Anti-VEGF is usually given at the same time to treat the underlying CNVM and, with the injection volume required, anterior chamber (AC) paracentesis is performed one or more times to maintain optic nerve head perfusion. Injection should be performed in a clean room using routine intravitreal injection protocol, with a dilated pupil to allow visualisation of the gas bubble and to check optic nerve head perfusion post-procedure. A rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) is expected but typically equilibrates over several hours. Non-contact IOP methods, such as iCare, can be inaccurate after AC paracentesis and with gas in the eye. Numerous combinations of doses, types of gas and addition of anti-VEGF have been made and these have shown various results3. Ideal candidates are those with recent onset (< 2 weeks) of mainly subretinal haemorrhage under the fovea or inferior macula, with the ability and willingness to posture following the procedure. SMH relatively superior to fovea may be a contraindication, as displacement could lead to haemorrhage being moved under the fovea. This technique is generally felt to be ineffective for pure sub-RPE haemorrhage. Posturing is either commenced immediately after the procedure or in the first 24 hours to allow dissolution of the clot. Strategies include partial or full face-down positioning.

4. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with subretinal tPA, anti-VEGF and gas

The principles of surgery are similar to clinic-based displacement methods but involve vitrectomy to allow direct access to the retina. A localised retinal detachment is induced in the superior macula by injecting balanced salt solution through the retina with a fine (eg. 39G) subretinal cannula, with subsequent subretinal injection of tPA +/- anti-VEGF to liquefy the clot, followed by gas tamponade. Multiple iterations of surgery have been described, with combinations of tPA, anti-VEGF, subretinal or intravitreal gas, as well as active evacuation of blood/clot by making a drainage retinotomy.

The Manchester group published their protocol for managing SMH, reporting a 77% success rate with pneumatic displacement alone and 87% overall when combined with surgery for those that failed pneumatic displacement6. Their patient cohort presented with a mean duration of four days (range 1-14 days) and visual acuities of 1.34 logMAR (Snellen 6/168). The successful group demonstrated improved visual acuity to 0.83 (Snellen 6/40.5). Three patients developed vitreous haemorrhage from pneumatic displacement and four had persistent subfoveal haemorrhage. One developed significant increase in IOP, requiring cyclodiode treatment, and ultimately had no perception of light. Complications in the vitrectomy group included retinal detachment and retinal incarceration.

In the Star study, 90 patients with nAMD-related SMH were studied7. The participants had predominantly sub-retinal haemorrhage with diameter more than two optic disc diameter (DD) and thickness of more than 100mm on OCT. One group underwent pars plana vitrectomy with subretinal tPA injection, intravitreal Ranibizumab and 20% SF6 gas and the other pneumatic displacement with intravitreal tPA, intravitreal ranibizumab, anterior chamber paracentesis then 0.3ml pure SF6. Both groups were asked to posture head upright, face forward 45⁰ for three days.

The surgery group gained 16.8 ETDRS letters and the pneumatic displacement group gained 16.4 letters. These were not statistically significant and there were no ocular safety concerns. In the Star study, those with small SMH (<2DD) and exclusive sub-RPE haemorrhage were excluded as they were good candidates for anti-VEGF monotherapy.

Hopefully there is high-quality evidence on the way with the Tiger study. This is a large, multi-site randomised controlled trial in Europe comparing vitrectomy, subretinal tPA, intravitreal aflibercept and pneumatic displacement to intravitreal aflibercept monotherapy8. It will add some much-needed high-quality evidence for treating this uncommon but devastating complication of nAMD.

A systematic review and meta-analysis compared the effectiveness of anti-VEGF injections and surgeries for SMH in AMD9. One of the key findings was that anti-VEGF monotherapy has a positive effect with a well-established safety profile and less variability in outcome, compared with surgical approaches8. This may be due to selection bias of the patient populations, however, as surgical intervention is more commonly offered to those with worse haemorrhages.

In summary, there is no strong evidence supporting vitrectomy with subretinal injection as the primary treatment for SMH. Clinic-based pneumatic displacement with combined intravitreal injection of tPA, anti-VEGF and gas is a technique that can be performed by any ophthalmologist with experience of intravitreal injections and should be considered in centres without immediate access to vitreoretinal surgeons.

Case study

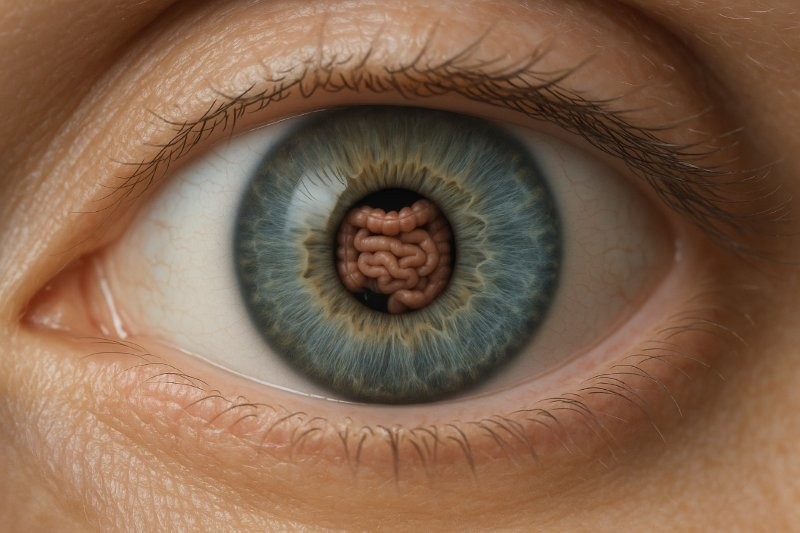

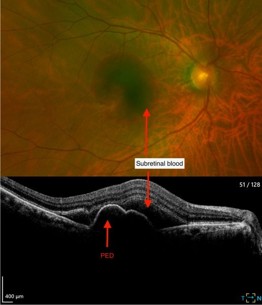

A 74-year-old fit and well Chinese man presented with a one-week history of right central blurring and visual acuity of 6/75. He was found to have submacular haemorrhage of around 6DDs with subretinal blood and coexisting pigment epithelial detachment confirmed on OCT (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Fundus image and OCT showing sub-macular

haemorrhage pigment epithelial detachment (PED)

Differential diagnosis for his submacular haemorrhage included nAMD and IPCV. He consented to pneumatic displacement with intravitreal alteplase, bevacizumab and 100% SF6 gas. This was performed under subconjunctival anaesthesia followed by face-down posturing until review the following day. Raised IOP was managed medically.

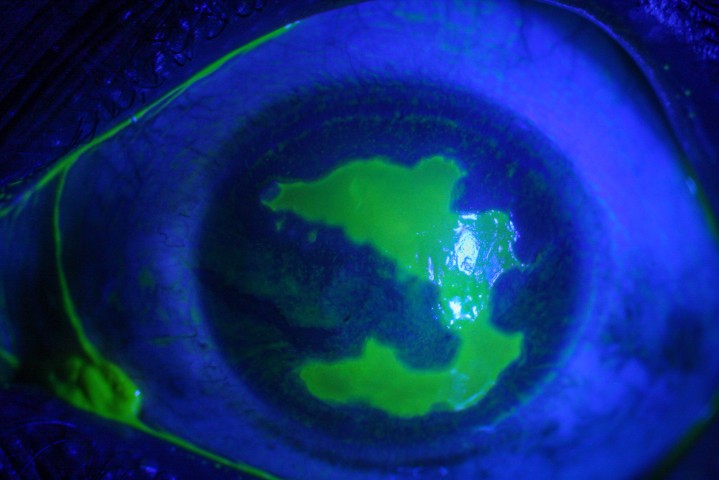

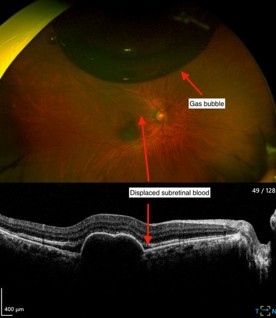

The following day, VA had improved to 6/24, and IOP was normal. Fig 2 shows inferior displacement of the submacular haemorrhage away from the fovea. The patient was instructed to continue face-down posturing for another two days. The patient subsequently continued monthly intravitreal bevacizumab injections, then moved to a treat-and-extend regimen.

Fig 2. Presence of gas bubble and

displaced subretinal blood

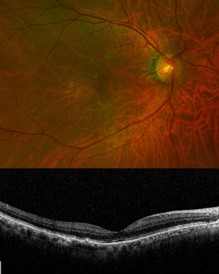

At his most recent review, seven months after initial presentation, visual acuity was 6/9.5 (6/7.5 with pinhole), without any recurrence of nAMD activity eight weeks after injection. His PED had also reduced, with subtle pigmentary changes only (see Fig 3).

Fig. 3 Final follow-up of the patient

showing good macular architecture

Take-away points for optometrists

- Recognise SMH promptly in patients with acute central vision loss.

- Urgently refer to the local ophthalmology service – pick up the phone!

References

- Al-Hity A, Steel DH, Yorston D, et al. Incidence of submacular haemorrhage (SMH) in Scotland: a Scottish Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit study. Eye. 2018;32:1890–1897.

- Gabrielle PH, Maitrias S, Nguyen V, et al. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of submacular haemorrhage with loss of vision in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in daily clinical practice: data from the FRB! registry. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100(8):e1569ee1578.

- Stanescu-Segall D, Balta F, Jackson TL. Submacular hemorrhage in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a synthesis of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61:18e32.

- Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Childs AL, et al. Surgery for hemorrhagic choroidal neovascular lesions of age-related macular degeneration: Ophthalmic findings: sst report no. 13. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1993-2006.

- Heriot W. Intravitreal gas and tPA: an outpatient procedure for subretinal haemorrhage. Vail Vitrectomy Meeting; March 10–15, 1996; Vail, CO.

- Chew GWM, Ivanova T, Patton N, et al. Stepwise approach to the management of submacular haemorrhage using pneumatic displacement and vitrectomy (Manchester Protocol). Retina. 2022;42(1):11–18.

- Gabrielle PH, Delyfer MN, Glacet-Bernard A, Conart JB, Uzzan J, Kodjikian L, et al. Surgery, tissue plasminogen activator, antiangiogenic agents and AMD study: a randomised controlled trial for submacular hemorrhage secondary to AMD. Ophthalmology. 2023 Sep;130(9):947-957.

- Jackson TL, Bunce C, Desai R, et al. Vitrectomy, subretinal tissue plasminogen activator and intravitreal gas for submacular haemorrhage secondary to exudative AMD (TIGER): study protocol for a phase 3, pan-European, two-group, non-commercial, active-control, observer-masked, superiority, randomised controlled surgical trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):99.

- Shaheen A, Mehra D, Ghalibafan S, Patel S, Buali F, Panneerselvam S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-VEGF injections and surgery for AMD-related submacular hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology Retina. 2024 Aug 3;9(1):4–12.

Dr Louis Han is the vitreoretinal fellow at Christchurch Hospital. He graduated from the University of Otago Medical School and was awarded the Postgraduate Diploma in Ophthalmic Basic Sciences with distinction in 2018. He was the recipient of the Gordon Sanderson Award for outstanding academic achievement in practical ophthalmic science.

Dr Oliver Comyn is a senior medical officer and vitreoretinal surgeon for Health New Zealand Christchurch. He chairs the New Zealand Save Sight Society and is an investigator on the Kriya Vision study of a novel gene therapy for geographic atrophy.