ARN a rare but important cause of uveitis

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) is a rare but serious form of infectious panuveitis. It is important to recognise it early since delays in diagnosis, which remain common, can lead to poorer visual outcomes. In this review we will cover typical clinical features and the current best management strategies.

Clinical features

The key clinical features of ARN are panuveitis with retinitis or retinal necrosis and vasculitis. The diagnostic criteria proposed by the Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group are summarised in Table 11. Most cases are caused either by varicella or herpes simplex viruses. There are several clues on clinical evaluation to help point towards the diagnosis of an infective retinitis.

History

Onset of symptoms is acute or subacute, most commonly including redness, pain or photophobia, blur and new-onset floaters. Between 70 and 90% of cases are unilateral at initial presentation, but second eye involvement can occur in up to 30% without treatment2.

Past medical history can include childhood encephalitis; incidence of ARN in these patients is reported to be 4–8% and can present decades later3. The patient may also report recent infection with either chicken pox or shingles, which can occur in any dermatome, ie. not necessarily V1 distribution. However, many patients have no known previous varicella or herpetic infection. Immunocompromise, including mild degrees, such as diabetes mellitus, also increases susceptibility to ARN, but most people who develop it are immunocompetent4.

Anterior segment signs

Anterior uveitis is typically present, ranging from mild to severe and may be granulomatous. Keratic precipitates may be pigmented due to ischaemic necrosis of the iris5. Iris intrastromal haemorrhage is a less common feature but, if seen, is highly suggestive of viral aetiology for the uveitis. Later, iris transillumination defects may develop. Raised intraocular pressure (IOP) at time of first presentation is common and likely represents a trabeculitis.

Posterior segment signs

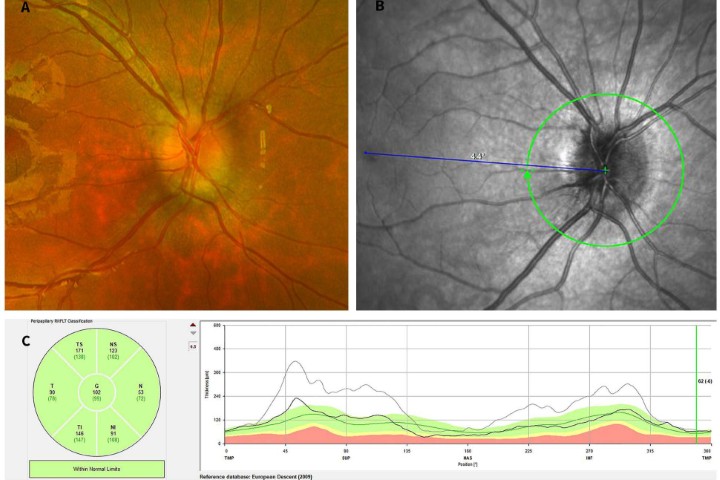

Vitritis is a feature of ARN and can vary from mild to severe. Dilated retinal examination may show patches of multifocal white infiltrates, most commonly in the retinal periphery. Initially, this may be subtle and these areas often evolve to become more confluent and sharply demarcated as necrosis develops. Lesions spread posteriorly without treatment and this can be a rapid process. Involvement of more than 25% of the retina is a poor prognostic sign (Fig 1)6.

Fig 1. Optos images of right (A) and left fundus (B) in a case of bilateral VZV acute retinal necrosis with vitritis, widespread multifocal retinitis, retinal haemorrhages and optic nerve swelling

Patients with ARN almost invariably have vasculitis – this is often occlusive, predominantly affects arteries and may have associated intraretinal haemorrhages (Figs 2 and 3). Any patient presenting acutely with signs of retinal vasculitis must have a careful dilated examination of the retinal periphery of both eyes. Optic nerve swelling may be present and may occur with or without optic nerve dysfunction.

Fig 2. Optos image of left fundus in VZV ARN showing

segmental occlusive vasculitis, predominantly affecting

arteries, with multifocal white retinal infiltrates

extending posteriorly

Fig 3. Optos image of right fundus in VZV acute

retinal necrosis with extensive haemorrhagic

occlusive vasculitis

Investigations

Anterior chamber tap

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for infective retinitis in any acute panuveitis cases or if there are any red flags on clinical examination (Table 1). The definitive diagnosis of ARN is made by a positive anterior chamber or vitreous sample, in a clinically compatible situation. Anterior chamber tap is usually recommended over vitreous sampling. The sensitivity of PCR testing on anterior chamber tap is very high for herpes viruses, with sensitivity between 84 and 100%7. This is a safer technique than vitreous sampling and is more comfortable for the patient.

Multimodal imaging

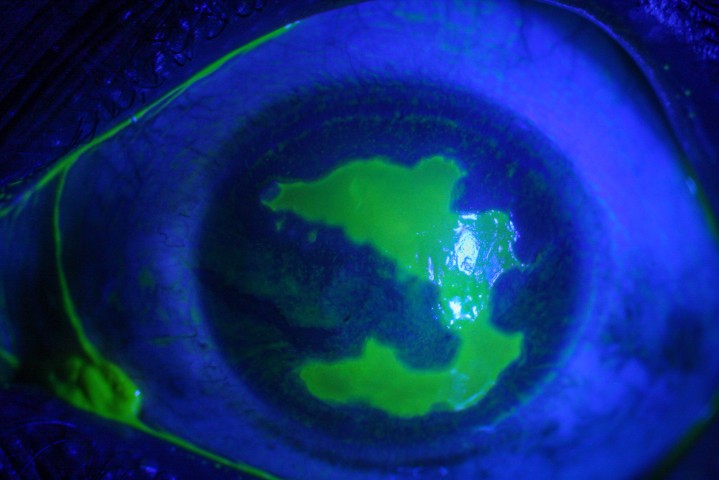

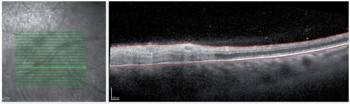

Diagnosis of ARN is clinical, supported by laboratory investigations, but multimodal imaging can aid diagnosis. Ultra-widefield photography can be useful to identify peripheral retinitis in ARN, particularly when the fundal view is obscured by vitritis or the patient is photophobic and difficult to examine. OCT imaging is not always possible through the retinitis as it is frequently too peripheral; when possible, we see hyperreflectivity and thickening of the inner plexiform layer early in presentation, followed by full thickness involvement of all retinal layers (Fig 4)5.

Fig 4. OCT imaging of patient in Fig 3, through retina (inferotemporal posterior pole) demonstrating full thickness hyperreflectivity and loss of retinal architecture ie. full thickness retinitis

Treatment

Antivirals

If ARN or any infective retinitis is suspected, treatment should be instituted promptly. This can be refined once results from investigations become available. We recommend starting oral valaciclovir 2g TDS (renal dose adjusted if needed)5. If the patient is immunocompromised, or the clinical appearance is not classic for ARN, consider also giving treatment to cover toxoplasmosis (cotrimoxazole 960mg BD) until lab results are available.

The initial intensive phase continues for at least six weeks (and until all active retinitis has healed). Intravenous aciclovir 10mg/kg/dose has enhanced bioavailability in the eye and this is still used in severe cases for up to 10 days before switching back to oral valaciclovir.

Intravitreal foscarnet (2.4mg/0.1ml) should be considered for severe cases or those with posterior lesions. This can be repeated once or twice weekly until the retinitis is healing.

Longer term, prophylactic antiviral treatment must continue for at least three months. This reduces recurrences in the affected eye and, importantly, decreases the risk of second-eye involvement from 75.3% to 35.1%.2. There is no consensus in the literature about optimal duration and prophylaxis should continue indefinitely if the patient is immunocompromised; it should be considered in an only-eye scenario or following recurrent ARN. Some uveitis specialists advocate for lifelong valaciclovir prophylaxis after ARN caused by Varicella zoster virus (VZV), due to the worse visual outcomes. Usual dose range is 500mg to 1g BD.

Topical and systemic corticosteroid

Topical steroid should be used to control anterior uveitis, in conjunction with systemic antivirals. Anterior segment inflammation can be severe and persistent.

Oral steroid may be added 24 to 48 hours after initiation of antiviral treatment if there is significant vitritis present, often in doses of 0.5mg/kg/day, then gradual tapering. The role of steroid has not been conclusively established and should not be given without systemic antiviral cover5.

Intravitreal steroid injections are generally considered contraindicated in the presence of any infectious uveitis, due to the risk of exacerbating viral replication and worsening necrosis.

Prophylactic laser or vitrectomy

There is high risk of retinal detachment following ARN (up to 70%) and some authors have suggested use of prophylactic barrier laser to reduce this risk. The literature around this is mixed and there may be selection bias in the published series, as more severe cases of ARN tend to have more vitritis and the retinal view may be too poor to allow for retinal laser8.

Similarly, while early pars plana vitrectomy has been suggested, at this stage the evidence does not fully support this surgery and there are no randomised controlled trials to date9.

Complications

Cystoid macular oedema (CMO)

CMO tends to be absent initially but can complicate visual rehabilitation later. Management is challenging if it does not respond well to topical steroid and NSAIDs. Intravitreal anti-VEGF agents can be trialled, but there is limited evidence for their efficacy in ARN. Care must be used with any long-acting steroid injections due to risk of reactivation of ARN, even with antiviral cover. Oral prednisone combined with oral antivirals can be effective; however, relapses are common as prednisone is tapered5.

Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is reported in 2% of cases at initial diagnosis and 47–70% will eventually develop a retinal detachment according to a meta-analysis (Fig 5)6,10.

Fig 5. Optos image of left fundus in VZV ARN with

rhegmatogenous retinal detachment several months

following initial presentation

Ischaemia, optic atrophy, glaucoma

Occlusive vasculitis can result in ischaemia and secondary neovascularisation. Vision loss can also be a result of optic atrophy or glaucoma due to uncontrolled IOP.

Prognosis

ARN still has a guarded prognosis, with around half of patients having final vision of 6/60 or worse in the affected eye. Age >80 years, immunocompromise, retinitis involving more than 25% of the retina and development of retinal detachment are all poor risk factors6. The main modifiable factor that impacts on prognosis is timely diagnosis4,6.

Take-home messages

ARN is a rare but important cause of uveitis that still carries a very guarded prognosis. Prompt diagnosis and initiation of treatment may improve visual outcomes and reduce risk of complications. Any patient with a clinical picture suspicious for infective retinitis should be referred for prompt assessment.

Table 1. SUN criteria for ARN diagnosis

References

- Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification criteria for acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthal 2021; 228: 237-44

- Palay D, Sternberg P et al. Decrease in the risk of bilateral acute retinal necrosis by acyclovir therapy. Am J Ophthal 1991; 112(3):250-5

- Todokoro D, Kamei S et al. Acute retinal necrosis following herpes simplex encephalitis: a nationwide survey in Japan. Jpn J Ophthal 2019; 63: 304-9

- Sims J, Yeoh J et al. Acute retinal necrosis: a case series with clinical features and treatment outcomes. Clin Exp Ophthal 2009; 37: 473-7

- Kalogeropoulos D, Afshar F et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in acute retinal necrosis; an update. Eye 2024; 38: 1816-1826

- Butler N, Moradi A et al. Acute Retinal Necrosis: presenting characteristics and clinical outcomes in a cohort of PCR-positive patients. Am J Ophthal 2017; 179:179-189

- Schoenberger S, Kim S et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Retinal Necrosis: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017 Mar;124(3):382-392

- Chen M, Zhang M, Chen H. Efficiency of laser photocoagulation on the prevention of retinal detachment in acute retinal necrosis: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Retina. 2022 Sep 1;42(9):1702-1708

- Risseeuw S, De Boer J et al. Risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in acute retinal necrosis with and without prophylactic intervention. Am J Ophthal 2019; 206: 140-148

- Zhao X, Meng L et al. Retinal detachment after acute retinal necrosis and the efficacy of different interventions: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Retina 2021; 41: 965-78

Dr Jo Sims is a medical retina and uveitis specialist at Eyes and Eyelids and Greenlane Clinical Centre, where she set up the uveitis service. She is a trustee for Macular Degeneration NZ and is on the Pharmac ophthalmology subcommittee.

Dr Haya Al-Ani is currently a fourth-year ophthalmology trainee based in Auckland and is starting subspecialty training in uveitis in 2026.