Finding your ikigai

Aiko lived in a small town in Japan and was known for her beautiful, handcrafted pottery. She spent hours each day at her pottery wheel, shaping clay with delicate precision. One day, a backpacker stumbled across her workshop. Intrigued by her focus and passion, he watched as she moulded the clay, lost in the rhythm of her hands. “What keeps you so devoted to this craft?” the backpacker asked. “Surely, the work is tiring and the days long.” Aiko smiled but didn’t stop her work. “This is my ikigai,” she said, “the reason I wake up each morning with joy. It’s not just about the pots I make; it’s about the meaning behind each creation. Every piece tells a story, connects me with those who will use it, and fills a need in the world. This is what makes my life meaningful.” The backpacker, reflecting on his own life, realised he had been going through the motions, working without a sense of purpose. Inspired by Aiko’s words, he left with a new question in his heart: "What is my ikigai?"

This story, passed down through generations, highlights the transformative power of finding our ikigai – the deep sense of purpose that fuels motivation. But let’s be real: motivating yourself can sometimes feel a bit like we are fictional 18th century German adventurer Baron Munchausen – pulling ourselves out of a swamp by our own hair! This is where finding our ikigai comes in: less hair pulling and more fulfilment in our daily work and rituals.

Motivation comes in three forms: biological, extrinsic or intrinsic. You may not consider yourself much of a running enthusiast but, I assure you, if a hungry tiger escaped from the zoo and made a beeline towards you, you’d be highly motivated to beat Bolt’s world record (or at least run a little faster than everyone else around you!). This is biological motivation: an innate desire to fulfil physiological needs – essentially, to stay alive. While this is helpful for the continuation of the species, it’s not likely to help us find fulfilment at work!

Extrinsic motivation, we may be more familiar with. This is the carrot in the old carrot-or-stick approach to motivation – if I achieve a certain target, I get a reward. Again, some of us enjoy this type of motivation, but for most it’s not what lights their fire. The most powerful form of motivation is intrinsic motivation: doing something for its inherent satisfaction rather than a separable consequence – our ikigai.

How do we find ikigai?

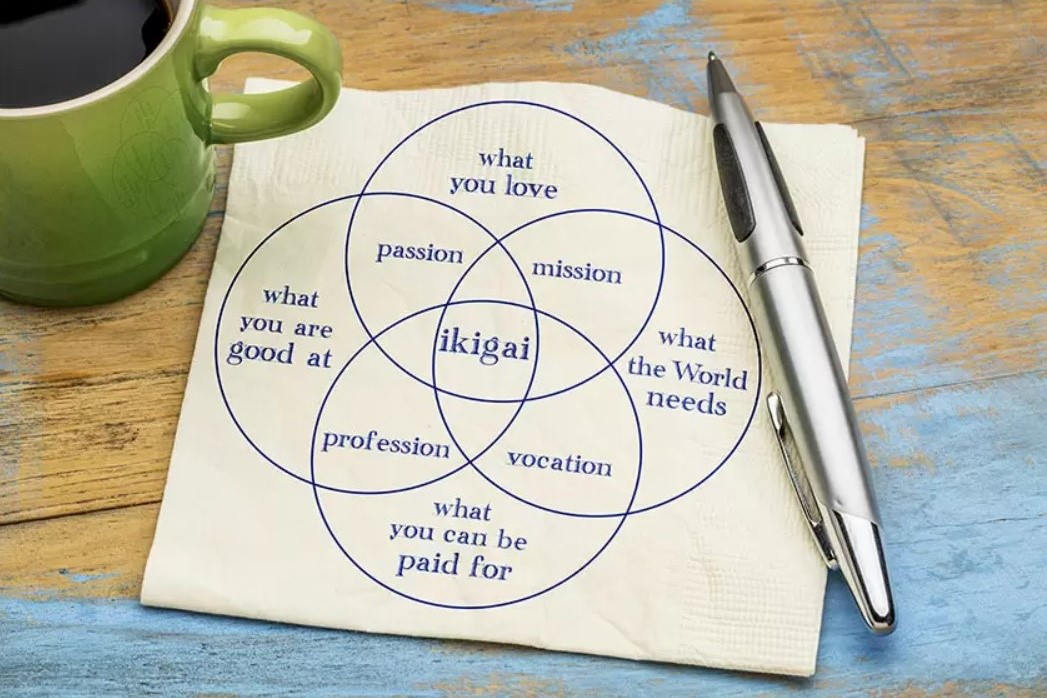

At its core, ikigai is our reason for being. It is found at the intersection of four key elements: what we love, what we are good at, what the world needs and what we can be paid for. When all four align, we experience a deep sense of purpose and joy in life.

In optometry, this could be the joy of helping someone see the world clearly for the first time, finding satisfaction in educating patients about eye health and preventing future vision loss, or the quiet satisfaction of knowing you’ve made a difference in someone’s life. Your ikigai doesn’t have to be grand or world-changing, it can be as simple as finding meaning in the patient interactions that fill your day.

Digging a little deeper into each of the elements can help us find our ikigai.

What you love (passion) – Which things are you are naturally drawn to, which energise you, things you would happily do even if there was no reward? What are you passionate about? What do you enjoy doing in your free time? What makes you lose track of time because you’re so engaged? This is the heart and soul of what gives your life meaning.

What you are good at (vocation) – Your skills, talents and strengths are things you’ve developed over time or for which you have a natural aptitude. What are yours? What do people often ask you for help with? What skills have you developed over the years?

What the world needs (mission) – This is about contributing to something larger than yourself – how your passions and talents can make a difference in the lives of others or address a need in the world. When your ikigai aligns with a meaningful mission, you feel a strong sense of purpose because you’re creating value beyond personal gain. How can you make a positive impact? What problems or needs in your community are you felt drawn to, to solve?

What you can be paid for (profession) – How can your passions, skills and contributions be turned into something practical and sustainable? What can you do that is valuable enough for others to pay you for? This is where your ikigai not only fulfils you but also allows you to make a living. When this element aligns with the others, you’re able to create a life of purpose while supporting yourself financially (and let’s face it, that’s important too!).

The sweet spot where all four of these elements overlap is your ikigai – a fulfiling purpose that brings satisfaction both personally and professionally. But discovering your ikigai is just the beginning. How do we stay connected to it in a fast-paced, demanding world filled with distractions? There are three more Japanese philosophies that can guide and support you.

Embracing imperfection: wabi-sabi

The Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi teaches us to appreciate the beauty in imperfection and transience. As a former – OK, recovering – perfectionist, I have been known to give up on things if I can’t do them perfectly (workouts, meal plans, articles…) but the story of the Japanese apprentice who was asked to tidy the Tea Master’s garden gave me a different perspective. He diligently worked all afternoon, clearing the weeds, the fallen cherry blossom, tidying the edges of the lawn, but when he stood back to admire his work he felt disappointed; although the garden was perfect, it was missing something. He walked over to the cherry tree and shook its branches until its remaining blossoms fell to the grass. Now the garden was beautiful. This philosophy has helped me stay motived, since striving for perfection, while noble, is never attainable and imperfection often brings with it a lesson and opportunity for growth (or at the very least a humorous anecdote!).

A practical way to apply wabi-sabi in your professional life is to embrace mistakes as opportunities to learn. When things go wrong, reflecting on ‘What did I learn from this experience?’ and ‘How can I grow from this mistake?’ takes me out of the ‘Well, that was a failure’ mindset and into more of a growth mindset. By embracing wabi-sabi, you’ll notice that it’s easier to stay motivated, even when the road gets bumpy. It encourages resilience, which leads nicely to gaman.

Gaman: the power of endurance

We face challenges in both our personal and professional worlds. Whether it's the stress of managing a busy clinic or the emotional weight of difficult patient cases, staying motivated during tough times requires a certain inner strength. This is where the Japanese concept of gaman comes in.

Gaman means enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity. It’s about pushing forward, even when things get tough, knowing that perseverance is part of the journey towards achieving something meaningful. That might be the quiet resilience to continue improving your skills, despite setbacks (blood in Schlemm’s canal with gonio, anyone?) or to find patience with difficult patients. Small daily practices that build resilience help build your gaman, such as taking a few moments to breathe deeply during stressful situations, choosing to respond rather than react to situations, or reflect on challenges you've overcome in the past and remind yourself of your ability to handle adversity. By practising gaman, you develop the mental strength to remain motivated, even on the tough days.

Embrace your ikigai

Just as Aiko found joy and purpose in her pottery, you too can find your ikigai. By embracing the imperfection of wabi-sabi and practising the resilience of gaman, you can sustain your motivation even through life’s challenges. Take a moment and ask yourself “What is my ikigai?” The answer may lead you to a deeper sense of purpose and a renewed drive in your personal and professional life.

Dr Emma Gillies, optometrist and PhD, runs a consultancy specialising in human dynamics, sales and leadership coaching and is director of professional services for Visioneering Technologies Australasia.