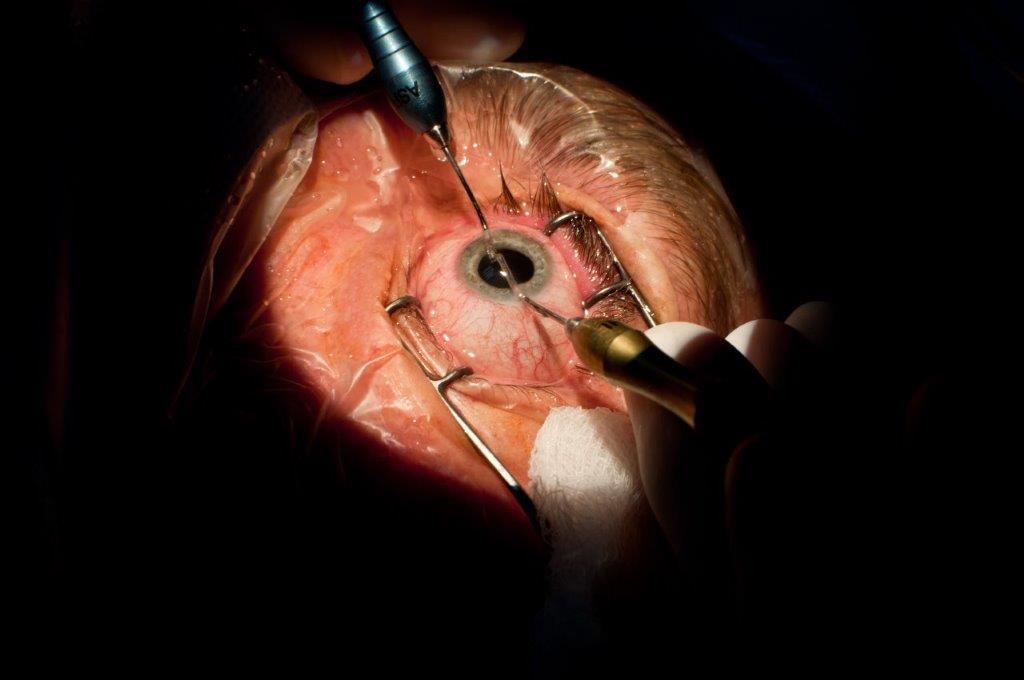

Importance of risk stratification in modern cataract surgery

Cataract surgery has transformed significantly over the decades, becoming one of the most performed and highly successful surgical procedures worldwide. It carries a small risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications, often quoted at around 2–5%; this varies across centres, as highlighted in Tables 1 and 21.

Fortunately, the majority of complications are mild and self-resolving; however, these can still increase operating resources and postoperative follow-ups and induce patient anxiety.

|

Complication |

Description |

|

Posterior capsular rupture |

Tear in the posterior capsule, potentially leading to vitreous loss and increased retinal detachment risk. |

|

Zonular dehiscence |

Detachment of zonular fibres, more commonly in pseudoexfoliation or trauma cases. |

|

Dropped nucleus or lens fragments |

Pieces of the lens falling into the vitreous cavity, often requiring subsequent pars plana vitrectomy. |

|

Corneal oedema |

Swelling from excessive phacoemulsification energy or endothelial damage. |

|

Incisional thermal burns |

Rare; caused by inadequate cooling of the phaco tip during ultrasonic lens removal. |

|

Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome |

Floppy iris prone to prolapse, commonly linked to alpha-blockers like tamsulosin. |

|

Iris trauma |

Accidental damage to the iris from instruments, manipulation or iris prolapse. |

|

Incorrect IOL placement |

Improper positioning or decentration of the lens implant. |

|

Inadequate capsular support for IOL |

Due to capsular or zonular complications – may require alternative lens fixation techniques (eg, scleral-fixated) |

|

Vitreous loss |

Often due to posterior capsular rupture, or zonular dehiscence – may require anterior vitrectomy. |

|

Suprachoroidal haemorrhage |

Rare but severe; blood collecting between choroid and sclera, often in high-risk cases (eg, hypertension). |

|

Phacoemulsification or IOL injector malfunction |

Issues with surgical instruments causing delays or complications. |

|

Incision issues cornea / sclera |

Poor wound construction can lead to leaks or instability. |

|

Retained lens material |

Residual lens fragments causing inflammation or secondary glaucoma. |

Table 1: Intraoperative complications of cataract surgery2

|

Complication |

Description |

|

Endophthalmitis |

Less than 1:1,000 cases but requires emergency treatment. Acute intraocular infection; symptoms can include pain, redness, and rapid vision loss typically in the first week post-op. |

|

Post-op inflammation |

Mild anterior chamber inflammation is common and treated with topical corticosteroids; severe or prolonged cases beyond 4–6 weeks need further investigation and intervention. |

|

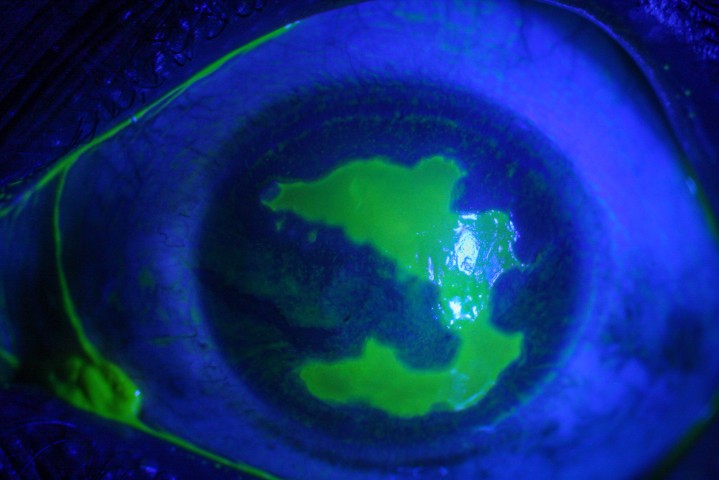

Corneal oedema |

Early post-op, mild/transient due to surgical trauma or Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. May also be gradual loss of corneal endothelial cells, potentially leading to decompensation. |

|

Raised intraocular pressure (IOP) |

Can occur due to retained viscoelastic material or in eyes with pre-existing glaucoma. |

|

Secondary glaucoma |

Uncommon; increased IOP due to chronic inflammation, debris, malpositioned IOL or retained lens fragments. |

|

Cystoid macular oedema (CMO) |

May affect 1:30. Swelling in the macula causing blurred or distorted central vision; treated with anti-inflammatory drops. |

|

Intraocular lens (IOL) dislocation |

Misplacement of the lens implant; may require repositioning. |

|

Dysphotopsias |

Visual disturbances (glare, halos, or shadows) due to IOL design. Typically settle with time in most cases. |

|

Posterior capsular opacification (PCO) |

Common over months to years. Clouding of the lens capsule, treated with YAG laser capsulotomy when vision is affected. |

|

Capsular phimosis |

Contraction of the capsular bag causing lens decentration, more common in pseudoexfoliation. |

|

Retinal detachment |

Uncommon; symptoms include floaters, flashes or shadows. More common in high myopes or complicated cases. |

|

Toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS) |

Uncommon; non-infectious inflammation from contaminants, mimics infection but resolves with anti-inflammatory treatment. |

Table 2: Postoperative ocular complications based on timing, adapted from Terveen et al 2022, based on Medicare claims in the United States post cataract procedures3

Risk factors of complications

It is generally accepted that as surgical precision increases, so does the complexity of managing diverse patient characteristics. A key summary of the common risk factors associated with cataract complications is found in Table 3. In an early study in the UK, approximately 40% of cataract cases contained one or more risk factors for cataract surgery, including diabetes, advanced cataracts and pseudoexfoliation syndrome. The incidence of surgical complications increases with the number of risk factors, from 4% with one risk factor to 32% with four or more risk factors4.

Patient systemic factors refer to the general health status, such as age, diabetes, medications and social requirements. In general, cataracts in the extremes of age necessitate more individualised and multi-disciplinary surgical approaches.

A large systematic review found that general health factors significantly increase the odd ratios of complications, such as hypertension (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 2.329, p < 0.001), diabetes mellitus (aOR = 2.818, p < 0.001), hyperlipidaemia (aOR = 1.702, p < 0.001), congestive heart failure (aOR = 2.891, p < 0.001), rheumatic disease (aOR = 1.965, p < 0.001) and kidney disease needing haemodialysis (aOR = 2.942, p < 0.001)5.

A tailored approach is required to mitigate the risks. For example, diabetic patients at high risk of maculopathy are often given concurrent intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) or steroids to reduce the risk of macular oedema after cataract surgery. Additionally, cognitive impairment, hearing impairment and physical frailty are also associated with worse complications, possibly due to noncompliance with intra- or post-operative instructions. Certain medications including tamsulosin (alpha-1 blocker) can cause intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, which creates intraoperative challenges6. The psychosocial history of the patient, including cultural biases, dependence needs and availability to travel, will also impact on the success of the surgery.

Patient ocular factors refer to specific ocular risk factors, such as the grading and type of cataracts, pupil size, previous ocular surgeries or comorbidities. Denser cataracts are associated with an increased risk of capsular rupture, zonular instability and dropped nucleus8. Small pupil, zonular weakness or iris abnormalities, such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome or synechiae, significantly increase the difficulty of surgery and may necessitate the intraoperative use of pupil expansion devices, resulting in increased postoperative inflammation, especially for junior trainees9. Patients with previous ocular surgeries have altered anatomy, complicating IOL power calculations and the choice of surgical approaches. Finally, concurrent ocular conditions such as advanced glaucoma, uveitis or retinal pathologies also influence visual outcomes by being unmasked by surgery, as well as influencing recovery.

Many anatomical ocular variations exist and some can affect surgical planning. Shallow anterior chamber is common in hyperopic eyes and increases the risk of intraoperative corneal endothelial damage if not addressed. The presence of extremely long or short axial length can pose challenges in IOL power calculation, increasing the risk of refractive surprises and the need for secondary IOLs8.

Amount of risk is increasing

With variations in demographics, expectations and technical complexities of cataract surgery, the amount of risk is increasing. First, there is an ageing patient demographic with associated comorbidities. Second, there are increased patient expectations regarding cataract surgery, placing additional emphasis on postoperative visual outcomes. Third, the complexity of procedures is increasing with the introduction of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery and premium IOLs, such as multifocal and extended depth of focus lenses9. This necessitates risk stratification for cataract surgery.

|

General health factors |

Ocular factors |

Anatomical factors |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

Advanced cataracts |

Deep set eyes or prominent brow |

|

Hypertension |

Ectopia lentis |

Small orbit or lid aperture |

|

Autoimmune diseases e.g. lupus, rheumatoid arthritis |

Small pupil size |

Long axial length or high myopia |

|

Immunosuppression |

Glaucoma |

Shallow anterior chamber |

|

Obesity |

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy |

Short axial length or microphthalmos |

|

Chronic respiratory diseases |

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome |

|

|

Age |

Previous ocular surgery |

|

|

Physical disability including posturing, hearing or cognitive impairment (affecting cooperation) |

Age-related macular degeneration/retinal disease |

|

|

Medications e.g. anticoagulants (minimal risk), alpha-1 blockers |

Corneal ectasia or high astigmatism |

Table 3: A summary of risk factors in cataract surgery

Risk stratification in cataract surgery

Risk stratification in cataract surgery is a process of categorising patients into groups based on their likelihood of experiencing negative health outcomes, using systemic, ocular and anatomical characteristics. The aim is to enhance patient safety, optimise surgical outcomes and ensure the efficient use of healthcare resources.

Many risk stratification scoring systems have been developed, such as the Muhtaseb and Buckinghamshire scoring systems, and different centres have developed implementations 4,12. The development of the New Zealand Cataract Risk Stratification System (NZCRS) follows a refinement of the Muhtaseb scoring system (M-score), with Table 4 showing the scoring template. The NZCRS differs from the M-score by the addition of oral alpha-receptor antagonists as a risk factor, and the allocation threshold of >3 or previous vitrectomy or only eye.

The NZCRS was developed from the four phases of the Auckland Cataract Study series from 2016–2020. Each phase utilised 500 consecutive cataract surgeries performed in the public hospital setting at Greenlane, Auckland. Phase 1 was a retrospective cohort study that compared the Buckinghamshire and Muhtaseb stratification systems and confirmed the increased risk of complications with risk factors12. Phase 2 was a prospective cohort study that used the M-score to stratify patients; if M>3, the case was allocated to senior eye surgeons. The intraoperative complication rate reduced from 8.4% to 5.0%13. A related observational study revealed a 2.6% rate of posterior capsular tear and 3.5% rate of cystoid macular oedema. Postoperatively, mean best-measured visual acuity was 6/9 and this was not significantly different between surgeon levels (p=0.234)14.

Phase 3 utilised the NZCRS prospectively, which identified 38% of cases as high-risk to be allocated to senior surgeons. Adherence was observed in n=448 and the intraoperative complication rate was 4.5%. In those where the NZCRS recommendation was not observed (n=52), the intraoperative complication rate was 9.6%15. Phase 4 was also a prospective cohort study where the NZCRS template was inserted into 621 consecutive case files without oversight of utilisation. NZCRS scores were calculated in n=500 cases and n=98 was scored as high risk. The recommendations for allocation were adhered to in 99% of 500 and resulted in overall intraoperative complications of 3.0% including iris prolapse of 1.6% and posterior capsule tear of 0.8%16.

These consecutive Auckland cataract studies showed a continued decreasing trend in frequency and severity of intraoperative complications with adherence to the NZCRS system. Furthermore, the NZCRS demonstrated lower complication rates to the M-score, and both scoring systems showed superiority over no risk stratification system.

|

Risk Factor |

Points |

Risk factor |

Points |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dense cataract (greater than grade 3) or total or white or no fundal view |

3 |

Shallow anterior chamber (<2.5mm) |

1 |

|

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome |

3 |

High ametropia (>6D myopia) |

1 |

|

Phacodonesis |

3 |

Posterior capsular plaque |

1 |

|

Oral alpha-receptor antagonist |

2 |

Posterior polar cataract |

1 |

|

Age more than 88 years |

1 |

Small pupil (<3mm with maximal dilation) |

1 |

|

Corneal scarring |

1 |

Miscellaneous risks e.g. poor positioning or cooperation |

1 |

|

Total points: |

|||

|

Previous vitrectomy |

Yes or No |

Only eye |

Yes or No |

|

Interpretation: |

If total points >3 OR Yes to Previous vitrectomy OR Yes to only eye, then allocation to fellow or SMO only |

||

Table 4: NZCRS template used in risk stratification prior to planned cataract surgery. Adapted from Auckland Cataract Study IV 16

Benefits of risk stratification

Risk stratification has been shown to improve patient safety, optimise visual outcomes, allow efficient resource utilisation and enhance overall patient satisfaction. By identifying and addressing risk factors preoperatively, surgeons can better anticipate challenges, personalise surgical plans and improve patient outcomes and satisfaction4. Risk stratification will also aid in prioritising patients and allocating resources effectively, ensuring high-risk cases receive greater attention. The application of a cataract surgery stratification system in surgery allocation, as shown by Tsinopoulos et al (2013), resulted in a reduction in complication rates (3.2% compared with 5.9%)10. By discussing realistic expectations, patients are better informed, leading to greater trust and satisfaction.

What challenges exist in risk stratification

As phase 4 of the Auckland cataract studies showed, despite the well-evidenced benefits of cataract risk stratification systems, the utilisation rate was still only about 80%. This may be due to logistical factors such as timing of patients’ attendance, being over-looked by clinical staff or being ignored by the surgical team. It is acknowledged that comprehensive assessment may be difficult in busy or resource-limited clinical settings. There is also inconsistent application of risk stratification protocols across centres, requiring ongoing education and training.

The future of cataract surgery will likely see greater integration of technology and tools such as artificial-intelligence-driven predictive models, where advanced algorithms trained on large data subsets can be used to predict outcomes and guide decision making.

Conclusions

Risk stratification is a cornerstone of modern cataract surgery, allowing ophthalmologists and trainees to navigate the complexities of diverse patient profiles while delivering excellent outcomes. By systematically identifying and addressing the potential risks, surgeons can enhance patient safety, optimise visual results and improve overall efficiency in surgical care, as demonstrated in New Zealand by the Auckland Cataract Study series. As cataract surgery continues to evolve, further refinements to the risk stratification system will ensure that this procedure remains at the forefront of precision medicine.

References:

1. Chan E, Mahroo OAR, Spalton DJ. Complications of cataract surgery. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2010;93(6):379-89.

2. Magyar M, Sándor GL, Ujváry L, Nagy ZZ, Tóth G. Intraoperative complication rates in cataract surgery performed by resident trainees and staff surgeons in a tertiary eyecare center in Hungary. International journal of ophthalmology. 2022;15(4):586-90.

3. Terveen D, Berdahl J, Dhariwal M, Meng Q. Real-World Cataract Surgery Complications and Secondary Interventions Incidence Rates: An Analysis of US Medicare Claims Database. J Ophthalmol. 2022;2022:8653476.

4. Muhtaseb M, Kalhoro A, Ionides A. A system for preoperative stratification of cataract patients according to risk of intraoperative complications: a prospective analysis of 1441 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(10):1242-6.

5. Lin IH, Lee CY, Chen JT, Chen YH, Chung CH, Sun CA, et al. Predisposing Factors for Severe Complications after Cataract Surgery: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(15).

6. Amin K, Fong K, Horgan SE. Incidence of intra-operative floppy iris syndrome in a U.K. district general hospital and implications for future workload. Surgeon. 2008;6(4):207-9.

7. Waghamare SR, Prasad S, Sankarananthan R, Venkatalakshmi S, Nagu K, Sundar B, Shekhar M. Nucleus drop following phacoemulsification surgery: Incidence, risk factors and clinical outcomes. Int Ophthalmol. 2024;44(1):247.

8. Kang C, Lee MJ, Chomsky A, Oetting TA, Greenberg PB. Risk factors for complications in resident-performed cataract surgery: A systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024;69(4):638-45.

9. Oustoglou E, Tzamalis A, Mamais I, Dermenoudi M, Tsaousis KT, Ziakas N, Tsinopoulos I. Reoperations After Cataract Surgery: Is the Incidence Predictable Through a Risk Factor Stratification System? Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10693.

10. Tsinopoulos IT, Lamprogiannis LP, Tsaousis KT, Mataftsi A, Symeonidis C, Chalvatzis NT, Dimitrakos SA. Surgical outcomes in phacoemulsification after application of a risk stratification system. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:895-9.

11. See CW, Iftikhar M, Woreta FA. Preoperative evaluation for cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30(1):3-8.

12. Kim BZ, Patel DV, Sherwin T, McGhee CN. The Auckland Cataract Study: Assessing Preoperative Risk Stratification Systems for Phacoemulsification Surgery in a Teaching Hospital. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;171:145-50.

13. Kim BZ, Patel DV, McKelvie J, Sherwin T, McGhee CNJ. The Auckland Cataract Study II: Reducing Complications by Preoperative Risk Stratification and Case Allocation in a Teaching Hospital. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;181:20-5.

14. Kim BZ, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Auckland cataract study 2: clinical outcomes of phacoemulsification cataract surgery in a public teaching hospital. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45(6):584-91.

15. Han JV, Patel DV, Wallace HB, Kim BZ, Sherwin T, McGhee CNJ. Auckland Cataract Study III: Refining Preoperative Assessment With Cataract Risk Stratification to Reduce Intraoperative Complications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:253-4.

16. Han JV, Patel DV, Liu K, Kim BZ, Sherwin T, McGhee CNJ. Auckland Cataract Study IV: Practical application of NZCRS cataract risk stratification to reduce phacoemulsification complications. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;48(3):311-8.

Dr Yuanzhang Jiao is a non-training ophthalmology registrar and has a strong research background in inherited retinal diseases, optic nerve drusen and retinoblastoma. Awarded for excellence in ophthalmic optics, he has extensive clinical experience and interests in teaching.

Associate Professor Jie Zhang is a vision scientist at the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Auckland, and the manager of the NZNEC microsurgical and cataract virtual reality training unit. She has specific research interests in both laboratory and clinical aspects of the cornea and anterior segment.

Professor Charles McGhee heads the Department of Ophthalmology and is director of the New Zealand National Eye Centre (NZNEC) at the University of Auckland. His interests include keratoconus, corneal diseases and corneal transplantation, complex cataract and anterior segment trauma, and complex anterior segment pathology, including iris and conjunctival melanoma and other rare anterior segment tumours, for which he receives nationwide referrals.