Keratoconus care – past, present and future

Keratoconus appears both more common and more severe in Aotearoa than in many other countries and it has been the most common indication for corneal transplantation in New Zealand for several decades. Collagen corneal cross-linking (CXL) provides the opportunity to halt or slow the progression of keratoconus and has been available in Auckland since 2007.

Drew Jones' article in the December 2021 edition of NZ Optics highlighted a key aspect of keratoconus management, establishing the capacity to carry out CXL treatment in New Zealand, while discussing the possible need for allied health professionals to conduct the procedures. However, a discussion focusing on surgical capacity alone does not accurately encompass the entirety of the challenges faced in delivering appropriate care for those with keratoconus. Undoubtedly, the CXL procedure itself is a critical aspect of the contemporary management of keratoconus; however, inequity in the delivery of CXL and the upstream and downstream aspects of managing keratoconus are arguably more important to address, namely: early diagnosis, optical correction, referral of appropriate cases for ongoing management and visual rehabilitation.

In this article, as early leaders of this treatment modality in New Zealand, we wish to discuss the context of the past and present management of keratoconus in the University of Auckland (UoA) and the Auckland District Health Board (ADHB) clinics, and highlight approaches being used to both increase efficiency and produce a more equitable service.

Early detection, referral and intervention remains a challenge

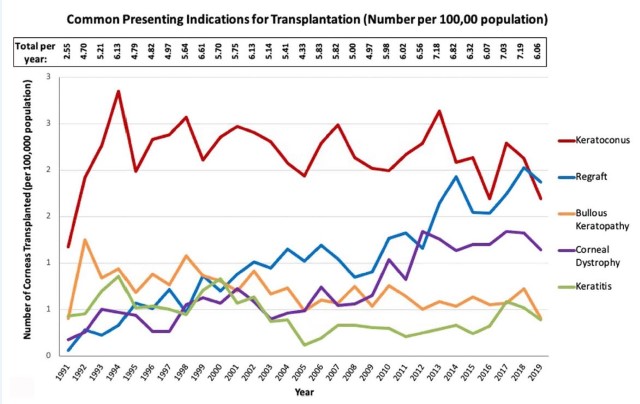

CXL is very effective for preventing disease progression. Long-term investigations demonstrate that disease stability is maintained for at least 10 years following intervention¹. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that after CXL is provided on a wider scale in a population, the proportion of corneal transplantations performed for keratoconus drops significantly². Research conducted by our team has demonstrated this trend is occurring in Aotearoa and in 2019 keratoconus became the second, rather than first, main indication for transplantation since indications have been recorded (Fig 1)³.

Fig 1. Total corneal transplants performed each year in New Zealand, grouped by primary indication for surgery, represented by common primary presenting indications per 100,000 population³

Studies in Aotearoa have demonstrated that keratoconus is both more common and severe in Māori and Pacific peoples – a phenomenon noted both in Auckland and nationwide⁴,⁵. Dr Lize Angelo is currently completing a doctorate focused on assessing inequity in access to keratoconus care in ADHB. Interestingly, preliminary results suggest that Māori and Pacific peoples are less likely to attend their first specialist assessment (FSA), with just 50% of appointments being attended (compared to 90% in European and Asian ethnicities). Furthermore, Māori and Pacific peoples have significantly more advanced, severe keratoconus in both groups when compared to all other ethnicities. Unfortunately, the delay in presentation to FSA appointments and the compounding effect of re-appointments, may result in delays in treatment and preventable disease progression.

Early detection and maintenance of functionally normal unaided or spectacle-corrected vision is possible with CXL. The current policy in ADHB is that patients under the age of 18 with definite keratoconus undergo CXL, with or without evidence of progression. Thus, optometrists are encouraged to refer these patients to the ADHB service upon diagnosis or suspicion of keratoconus. However, this policy does not necessarily represent the optimum allocation of resources in a cash-strapped hospital service, as although 77% in this age group progress, around a quarter may not progress⁶. Nonetheless, the significant issue of non-attendance becomes a factor to consider in this younger cohort and thus the benefit of conducting CXL on an eye with definite keratoconus perhaps outweighs the risk of delaying CXL to confirm keratoconus progression. Further research into predicting which patients will progress is a current project in our team and will allow for a more nuanced approach to monitoring keratoconus and prioritising the allocation of CXL procedures.

Are there significant waiting times for CXL in ADHB?

With a growing population and relative underfunding of health (plus a pandemic) there will never be a zero-waiting time for public healthcare in New Zealand, but for non-urgent conditions (such as keratoconus) this should typically be less than four months. Interestingly, waiting for outpatient attendance accounts for a significant proportion of the perceived issue around CXL capacity. However, keratoconus-specific FSA clinics in ADHB have substantially increased in capacity from 150 per year in 2019 to a projected 400 per year in 2022. There has been an accompanying increase in the number of CXL procedures performed, with capacity growing from around 100 in 2017 to a potential 350 per annum in 2022 (Fig 2).

Fig 2. CXL procedures performed in ADHB since the service began in 2014. Capacity and usage are presented for the years this was audited 2020-present. Planned capacity for 2022, also presented

Crucially, in 2019, it was noted that the number of crosslinking procedures being offered was significantly more than those taken up by patients! Subsequently, the CXL service has been prospectively audited, noting that approximately 15% of planned surgical procedures are not attended! A recent study by our team demonstrated that Māori and Pacific patients have longer wait times for CXL, which may result in disease progression. However, we did not specifically assess if these patients had failed to attend an earlier treatment offer⁷.

Assessing such equity in wait times led us to further investigate why there was a difference in wait times for CXL related to ethnicity. An audit of attendance for CXL procedures demonstrated that 90% of the procedures not attended were by patients who self-identified as Māori or Pacific peoples. This has led us to establish a broader, multi-disciplinary project involving Māori and Pasifika researchers to look into potential barriers, improved communication and improved uptake of corneal services in relation to keratoconus and CXL. We hope to launch this study in mid-2022.

Notably, at any one time, with referrals from six corneal subspecialty clinics and the keratoconus-CXL service, there are only 50-60 patients on the waitlist for CXL in ADHB. With a capacity for five to eight CXL procedures per week the average wait time is three to four months to the first offered procedure. Clearly, if attendance at FSA clinics and CXL theatre lists was improved, the waiting time would also be further reduced to an entirely manageable time of <12 weeks.

Allied health professionals’ contribution

The ADHB keratoconus and crosslinking service is a long-term collaboration between the DHB and the UoA. The service includes staff from a wide array of backgrounds, including nurses, optometrists, senior and trainee ophthalmologists and clinical research fellows. Ophthalmic nursing staff play a key role in providing technical and administrative support. Therapeutic optometrists are involved in clinical assessments pre- and post-CXL but also play vital roles in disease detection in the community and providing visual rehabilitation (spectacles or contact lenses) following CXL (a lifelong requirement in most cases).

Community optometrists are increasingly likely to play a key role in post-CXL care. Indeed, there is currently a pilot, HRC-funded investigation underway aimed at determining if, with the correct training and imaging technology, all post-CXL care can be conducted safely and effectively by optometrists in the community at the same time as the provision of visual rehabilitation. The goal is to provide care nearer the need and reduce the number of appointments to reduce the burden on the patient and the hospital system.

The UoA/ADHB model utilises medically trained personnel to conduct the CXL procedures. While we agree that allied health professionals, including optometrists and ophthalmic nurses, could conduct CXL procedures, at present the CXL treatment per se is not the roadblock and adding non-medical proceduralists is surplus to requirement, especially if current capacity and cross-discipline care can be utilised more effectively.

Conclusion

The focus of the keratoconus care in UoA/ADHB is shifting away from simply increasing capacity, as we have in the past, to addressing the underlying inequity in the system by addressing patient and practitioner education, involving community optometrists, improving efficiency by decreasing non-attendance and thus improving the overall effectiveness of the service. Simply increasing capacity to perform CXL by increasing proceduralists – without considering the underlying population needs and upstream effects – could prove costly while doing nothing to address inequity in the system.

While the issues around inequity in eyecare in Aotearoa are complex and the subject of ongoing studies, it is clear patients of Māori and Pacific ethnicities and those of higher socio-economic deprivation have poorer access to keratoconus care. Thus, our focus should be on improving access to address poorer outcomes. A key step in the process is to engage in a culturally appropriate manner with Māori and Pacific communities to understand the reasons behind non-attendance and to work with these communities to improve uptake of assessment and treatment. Ultimately, this may include targeted community- school-based screening programmes for earlier disease detection and same-day-as-clinic-appointment slit-lamp-based corneal cross-linking – both research projects scheduled to commence this year.

References

- Raiskup F, Theuring A, Pillunat LE, Spoerl E. Corneal collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in progressive keratoconus: 10-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015 Jan;41(1):41-46

- Sandvik GF, Thorsrud A, Raen M, Ostern AE, Saethre M, Drolsum L. Does corneal collagen cross-linking reduce the need for keratoplasties in patients with keratoconus? Cornea 2015 Sep;34(9):991-995

- Chilibeck CM, Brookes NH, Gokul A, Kim BZ, Twohill HC, Moffatt SL, et al. Changing trends in corneal transplantation in Aotearoa/New Zealand, 1991 to 2020: effects of population growth, cataract surgery, endothelial keratoplasty and corneal cross-linking for keratoconus. Cornea 2021 Jul 15

- Jordan CA, Zamri A, Wheeldon C, Patel DV, Johnson R, McGhee CN. Computerised corneal tomography and associated features in a large New Zealand keratoconic population. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2011;37(8):1493-1501

- Gokul A, Ziaei M, Mathan JJ, Han JV, Misra SL, Patel DV, et al. The Aotearoa research into keratoconus study: geographic distribution, demographics and clinical characteristics of keratoconus in New Zealand. Cornea 2022 Jan 1;41(1):16-22

- Meyer JJ, Gokul A, Vellara HR, McGhee CNJ. Progression of keratoconus in children and adolescents. Br J Ophthalmol 2021 Sep 3

- Goh YW, Gokul A, Yadegarfar ME, Vellara H, Shew W, Patel D, et al. Prospective clinical study of keratoconus progression in patients awaiting corneal cross-linking. Cornea 2020 June 01

Dr Akilesh Gokul is a therapeutically qualified optometrist working as post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Ophthalmology, UoA, and in clinical practice in the provision of crosslinking in ADHB and primary care optometry. His main clinical and research interests are keratoconus, crosslinking and inequity in healthcare.

Dr Lize Angelo is a junior research fellow currently working toward her PhD in the Department of Ophthalmology, UoA. Her PhD aims to assess health disparities and inequities spanning referral, diagnosis and treatment (including crosslinking) of subjects with keratoconus.

Professor Charles McGhee is an anterior segment sub-specialist ophthalmologist and head of the Department of Ophthalmology, UoA. His clinical and research interests include keratoconus, CXL, corneal transplantation, cataract, ocular/iris melanoma and equity in the provision of ophthalmic care.