Macular oedema: new light on the horizon?

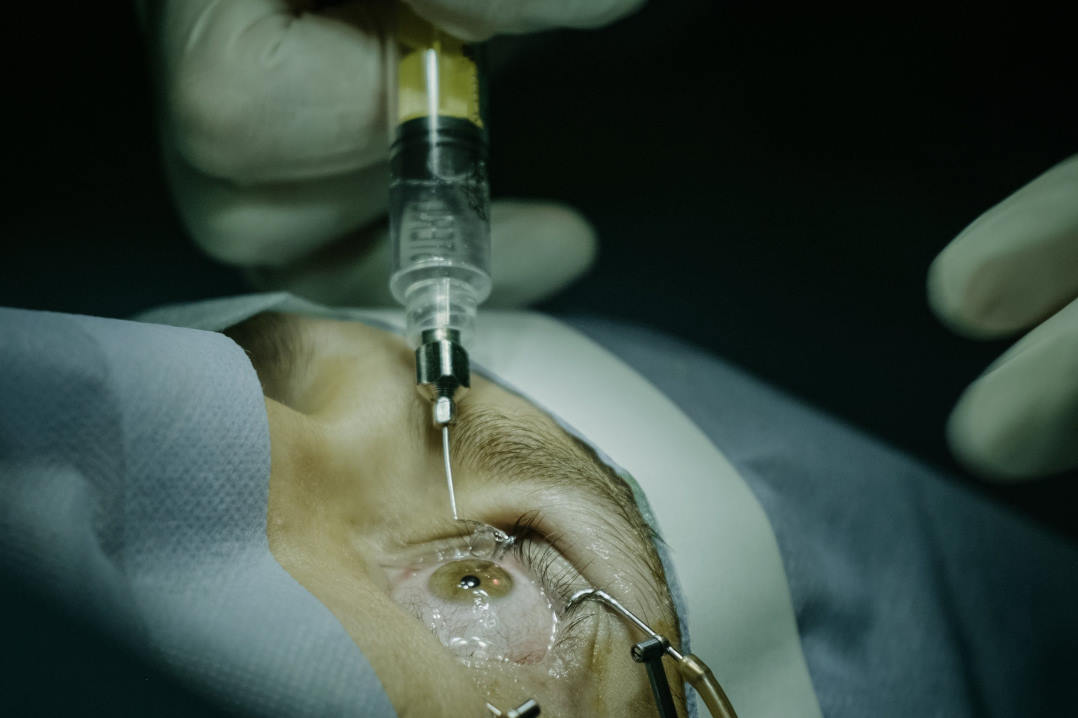

A Sydney Eye Hospital clinical trial is investigating the safety and efficacy of treating macular oedema with infrared light instead of the current mainstay eye injections.

“Eye injections work very well but most patients need to continue them for many years to maintain their vision because they only last for a month or two. A less invasive treatment may have many advantages and be better tolerated,” said a spokesperson from the Save Sight Institute’s (SSI) Macular Research Group (MRG), which is leading the study. “We are very excited to see what we will learn from this new potential treatment.”

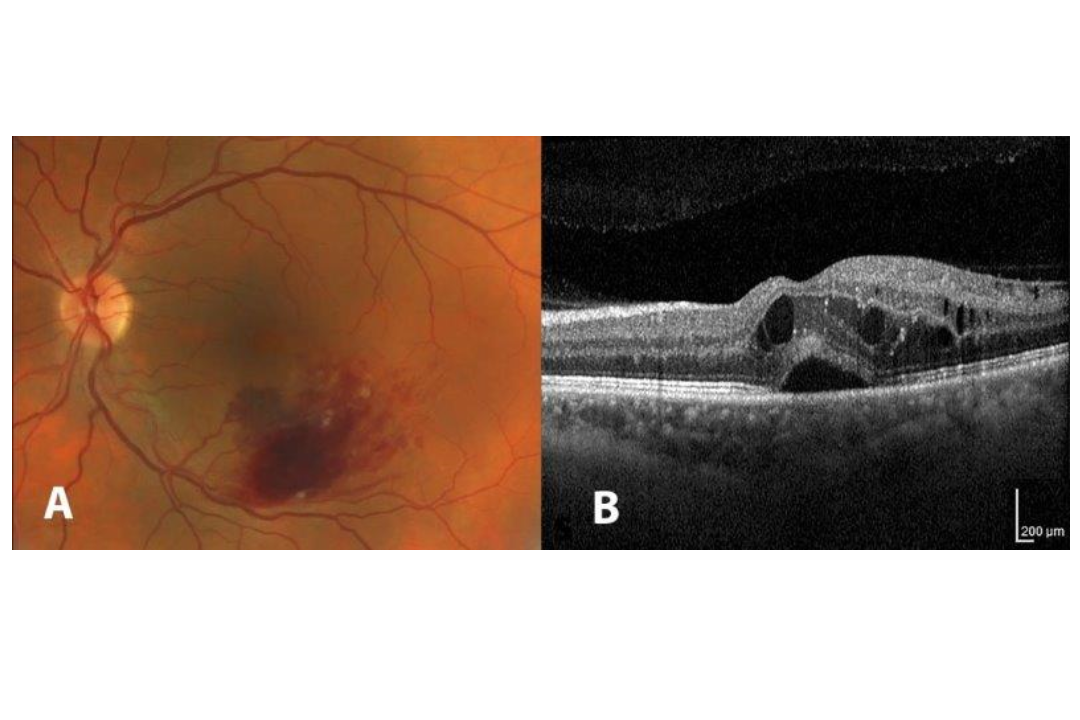

Retinal vein occlusions typically occur in patients over 50 years of age with cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, obesity and smoking, causing macular oedema and vision loss (Fig 1). Near infrared light treatment is thought to work by stimulating cellular metabolism and repair, researchers said.

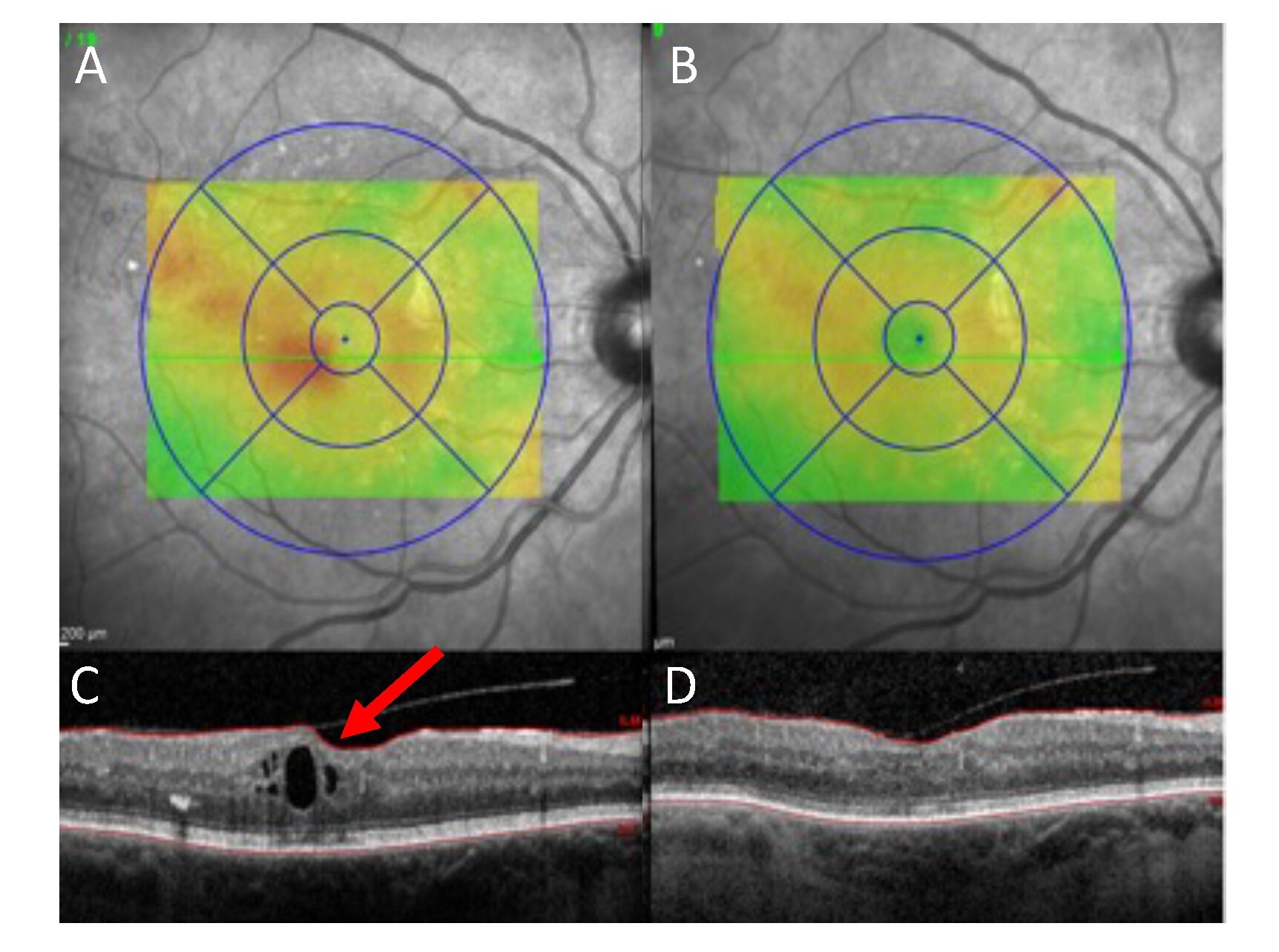

The MRG recently published results from a pilot study demonstrating that near infrared light was effective and safe when treating macular oedema due to diabetic retinopathy. Twelve 90-second treatment sessions with this light reduced the patients’ macular oedema (Fig 2) and the subsequent requirement for eye injections.

Fig 2. Pre- (A&C) and Post- (B&D) near infrared light treatment course for macular oedema due to diabetic retinopathy. A&B: Retinal images demonstrating thickening/swelling with the red shading. A is before treatment, B is following treatment with near infrared light. C&D: Cross section through the macula with macular oedema (red arrow, C) that resolves after near infrared light treatment (D). Credit: SSI

Meanwhile, The US Diabetic Retinopathy Research Collaboration is currently recruiting for a larger study with near infrared light, to confirm MRG’s findings.

The ‘Near infrared light for the treatment of macular oedema from retinal vein occlusions (NIRVO)’ study, which recently enrolled its third participant, may provide proof of principle for a definitive placebo-controlled clinical trial, which would be required before the treatment could be widely adopted, said SSI’s spokesperson.