Meet the… Low-vision co-ordinator

Sandy Grant is one of only a handful of low-vision co-ordinators in New Zealand. Susanne Bradley caught up with her to find out more.

Sandy Grant began her journey in low vision as a volunteer for the Canadian National Institute for the Blind’s (CNIB) recreational camps, working predominantly with blind but also with a few low-vision kids in Toronto. “Being a sighted guide is second nature for me; I’ve been doing it since I was 14. Getting on the bus with those kids was great; it made me realise that it is all about the people, not about the disability. The disability is part of them, but they are people first.”

After spending some time in Europe, Grant completed two programmes with CNIB, Rehabilitation Teaching and Orientation in Mobility Training. She emigrated to New Zealand in 1992 to work for the then Blind Foundation (now Blind Low Vision New Zealand). “One of my former teachers had always spoken very highly of New Zealand and one day someone put an ad on my desk. I applied and got the job, long distance.”

While her initial role involved working in community living with people with multiple disabilities, Grant soon moved into orientation mobility and rehab teaching. As a part of the new role, Grant took on rehab at the low-vision clinic, which was then run jointly by the Auckland District Health Board (ADHB) and the Blind Foundation, which evolved into her current role of Low Vision Clinic coordinator and therapist, at the Greenlane Clinical Centre.

Grant describes her role as being on the people-side of low vision – the ‘non-optical side’, focusing on the patient’s needs with the goal being the patient making the most of what vision they have. “Normally, when I see a patient, I don’t even test their visual acuity until the end of the interview. I assess how they get on at home, if they are living alone, if there are any safety issues and ask questions to find out if vision is indeed the sole culprit or if there are other co-morbidities coming into play.

“I try and hammer out what their needs are, from a vision point of view. Coming from a mobility background is quite helpful, coaxing people to overcome their pride and accepting help. I sometimes use the analogy of ‘Do you think people are going to remember the person who used the cane successfully or the person who fell down the stairs?’ It sounds harsh, but they take it on board and will often have a rethink later.”

The biggest challenge is getting people in early so they can adopt good low vision strategies, said Grant. “I’m somebody they can talk to about their diagnosis. I can show them the positives, show them what they can do and what services are available. If people leave here with a boost in their confidence and some positivity, then that’s great, we’ve done our job.”

The Covid lockdowns were particularly challenging in several ways for low-vision patients, especially those in hospital wards who didn’t receive their usual visits from BLVNZ staff, she said. “I felt like I was cramming things in, but I tried to cover the gap and visit those people, so they didn’t return home to nothing.”

If there was one positive of the lockdowns, however, it was the rise of telehealth, said Grant. “I’m now phoning all low-vision patients first and it works really well. Talking to the patient reassures them that we haven’t forgotten about them. There’s information I can pass on, like how to apply for a total mobility card. If they need to link up with BLVNZ, I can do that and save them from having to wait three or four months. At least they have a phone number and somebody they can ring if they need anything. I’m not a lifesaving kind of service but I can help chase something down if need be.”

For Grant, the patients are the highlights of her job. In 2020, she received the ADHB Local Hero Award, after being nominated by a patient and his wife. “To get that kind of feedback from patients is why I’m here; I love what I do and I’m very passionate about my job.”

Being a good listener is very important in her role, she said, to really listen to what people have to say. “You need to be able to go in whatever direction the patient is going and not have a set pattern; you need to be flexible and empathetic.” She also finds having a sense of humour helps, “Not making fun of anything, just being realistic in a lighter manner.”

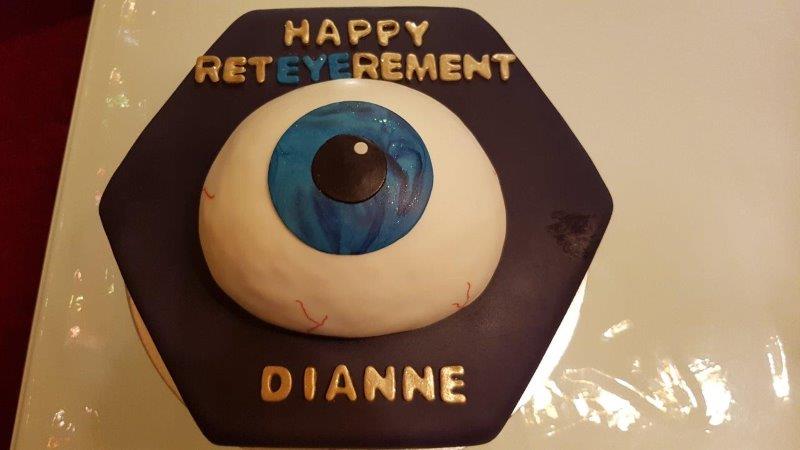

Grant also keeps busy with her second passion – cake making. “One of my all-time favourite cakes was the eyeball cake I made for Dr Dianne Sharp’s retirement party. My cakes aren’t huge like the ones on the British TV shows, but I think they taste better!” she laughs. Coming a close second to the cake making is Muriwai beach walks with springer spaniel Monty and her partner, and spending time with her first grandchild, 10-month-old Shiloh.

Sandy Grant's cake for Dr Dianne Sharp's retirement party