New non-contact corneal device, new study

Kiwi ophthalmologist, Dr Simon Dean has taken a novel approach to designing a state-of-the-art, non-contact corneal aesthesiometer (NCCA). Here he shares his thoughts on the device and its use in a new study investigating cold-sensitive nerve fibre pathways in ocular surface health and disease.

Corneal innervation is an interesting and somewhat complicated research area, as not all neural pathways are fully understood. What is known is that there is more than one type of sensory nerve supplying the cornea and they appear to have different roles. Cold thermoceptors (about 10% of corneal nerves), for example, not only detect cold but also wetness, and are thought to be sensitive to osmolarity as well - as tears evaporate they leave the salts behind, increasing osmolarity and resulting in discomfort. Therefore, their role in regulating basal tear production can be affected by pathological states such as dry eye where hyperosmolarity causes inflammation and damages the nerve endings.

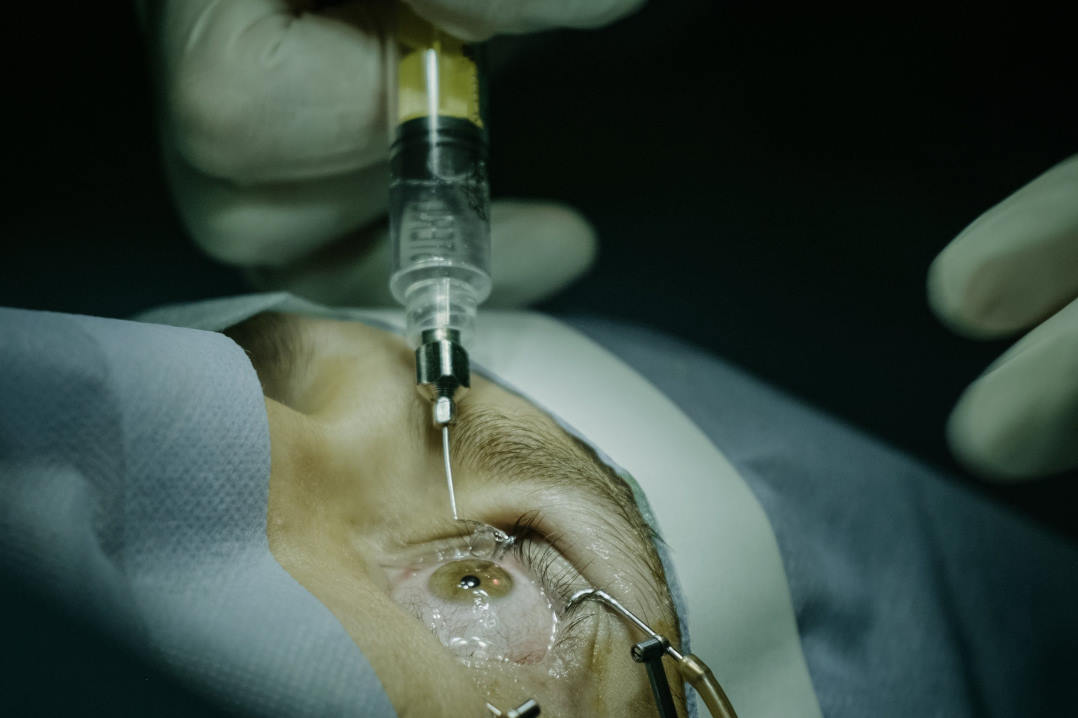

It is well known that HSV keratitis causes decreased corneal sensation and an anaesthetic cornea can succumb to ulceration in neurotrophic keratitis due to interruption of normal tear production and inadequate corneal wetting. Measuring the threshold of corneal sensitivity as objectively as possible is thus important and so it is valuable to have a tool to evaluate the normal and pathological ocular surface environment. While pain is subjective and can be scored quantitatively with a validated questionnaire, the status of corneal nerves can be observed with in vivo confocal microscopy and quantified by aesthesiometry.

Measuring corneal sensitivity objectively (by aesthesiometry) can be useful in a range of pathologies where corneal sensitivity may be altered. Traditionally, corneal sensitivity has been measured using a contact method, but this risks discomfort for the patient and damage to the, sometimes fragile, corneal epithelium. The earliest corneal sensitivity measuring tools were made of horsehair, which early eye health practitioners used to stimulate sensation from the patient’s cornea. Today the most common sensitivity tool is the handheld Cochet-Bonnet aesthesiometer. This uses a thin, retractable, nylon monofilament of constant diameter and variable length that extends up to 6cm. The length is progressively reduced, increasing the force required to bend, until the subject reports sensing the nylon.

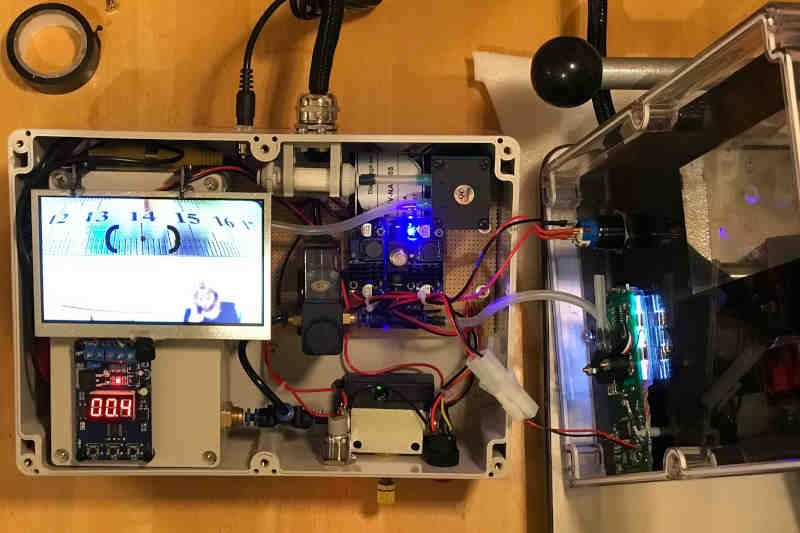

This new aesthesiometer is less invasive than the traditional contact method and also reduces the risk of transferring infection to the patient. It uses a gentle 0.9 second puff of air, the pressure of which can be increased incrementally until the patient detects the puff and reports some sensation. The air puff emerges from a 0.5mm diameter nozzle, 1 cm from the target and can be varied from 0.1 to about 20 millibars in pressure. The device can be used to test the sensitivity not only of the cornea, but of the conjunctiva, as well, including the tarsal (lid) conjunctiva, adjacent to the eyelid margin.

We have found normal corneal sensitivity falls in the range of 0.5 to 0.7 mbar. The device has a camera at the nozzle tip and a built-in video monitor to allow accurate alignment of the air puff tip. The latest version also has a wireless remote control to trigger the puff. Additionally, the air is able to be cooled, which may stimulate different nerve pathways thereby adding another dimension to investigations of corneal innervation in health and disease.

Corneal sensation generally reduces with increasing age and is affected by many different pathologies including multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular events, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, cocaine abuse, leprosy and tumours. Dry eye or tear film instability can also alter corneal sensation, with increased sensitivity sometimes resulting in excessive tear production in intermittent bursts with intervening episodes of stinging and burning sensations.

So in dry eye studies where reported discomfort is a common outcome measure, it is useful to be able to measure corneal sensitivity objectively as this helps to minimise the variability associated with patient reported outcomes. So I’m pleased to report that the new NCCA is being used in a joint New Zealand-Australia study being conducted by my partner Associate Professor Jennifer Craig from The University of Auckland and Dr Laura Downie from The University of Melbourne. The study is designed to investigate variations in corneal sensitivity with temperature and to further investigate thermally sensitive pathways to improve understanding of tear film homeostasis with a view to enabling eye care practitioners to better diagnose and manage dry eye disease.

Dr Simon Dean is a specialist cataract and refractive surgeon at the Manukau Superclinic and the Eye Institute in Auckland. He is active in teaching and research, is a well-known speaker and has designed and built several ophthalmic instruments, including a corneal collagen crosslinking device and, now, the new NCCA.