New tube designs a big step forward in glaucoma surgery

In choosing from the expanding list of options for glaucoma surgery, we should be seeking to optimise efficacy, safety and consider costs. An ideal glaucoma operation immediately results in: a stable pressure of 10mmHg without eye drops; no hypotony (pressures too low); should cost $10 and take 10 minutes. Of course, in reality, our surgical choices are far worse than this in every aspect and there are significant trade-offs between effectiveness and risk of complications.

Generally, tube implant surgery has been reserved for seriously challenging eyes, with both advanced glaucoma and risk factors that predict the failure from other operations, such as trabeculectomy.

The original Molteno tube and the longstanding Baerveldt and more recent Aurolab and ClearPath tubes all share a very similar design, with a 23G silicone tube, no valve and a plastic plate. The plate is important to prevent progressive fibrosis, which causes tubes to stop draining over time, but a large rigid plate can be slow to implant under extraocular muscles. For all of these designs, the 23G tube cannot be safely implanted without tying the tube off with a dissolving Vicryl tie1,2.

This tends to result in a month of unpredictable and potentially high pressures before the tie dissolves and, sometimes, the opening can be dramatic, with sudden hypotony after four weeks. Flow restrictors for this 23G tubing1,2 are 3-0 sutures, which do not provide very reliable flow regulation and are bulky under the conjunctiva and can become exposed and infected. Additionally, the most useful suture material, Supramid, is no longer available. All of these factors have made tube surgery somewhat daunting and therefore reserved for challenging eyes with few better options.

Looking back at my Molteno and Baerveldt tube surgery before 2023, in an audit of 54 consecutive public hospital tube implant cases from 2018–2023, all the eyes had significant risk factors for trabeculectomy failure or complications. Surgery would take 70–90 minutes, often needing general anaesthetic, described by registrars and nurses as the ‘paint dry’ technique. Around two-thirds of patients had undesirable high intraocular pressures (IOP) for the first month until the Vicryl tie dissolved and, for one-third of patients, the high pressure was a serious, difficult issue, despite the use of medications, such as Diamox.

I was also concerned to see a significant risk of exposure of the flow restrictor (16%), exposure of the tube or plate (11%) and a few cases of serious infection. There were also some cases with troublesome hypotony, which included cases led to corneal endothelial failure (9%). Notwithstanding the idea that these were difficult eyes with no better options, these outcomes concerned me.

The current landscape

In 2023, the ClearPath tube, with its smaller flexible plate, resulted in a much quicker technique, requiring just 30 minutes or so and usually requiring only local anaesthesia. However, the original ClearPath did not solve many of the short-term issues around 23G tubes with 3-0 flow restrictors, Vicryl ties and high pressures for the first month.

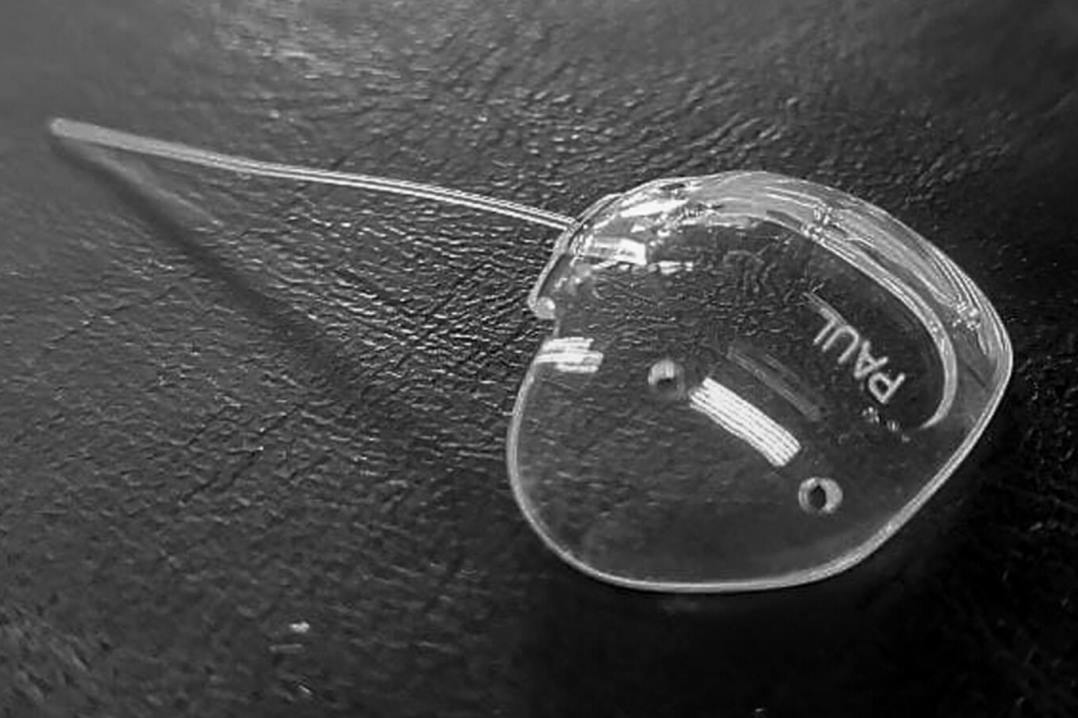

The innovation of the Paul tube (Fig 1) was the use of smaller tubing of around 26G3. This offers one big advantage: a predictable and gradual flow around a 6-0 Prolene suture flow restrictor, which means that the Paul tube does not need to be tied off with Vicryl (Fig 2).

Fig.2

The result is that the first postoperative month does not include nearly so many high pressures or glaucoma medications. With no tie, the flow restrictor can also be withdrawn in phases immediately, allowing persisting or uncontrollable high pressures to be addressed. The smaller tubing also has minor and theoretical advantages, in that it may be less likely to be exposed and less likely to damage the corneal endothelium in the longer term.

This has changed my experience significantly in the last 18 months – tube surgery is now a 30–45 minute procedure under local anaesthetic with the immediate IOP control and the quick visual recovery of a minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), but with the advantage of a robust, long-lasting design suited to complicated secondary glaucoma and low target pressures. The smaller 6-0 flow restrictor can be brought to the cornea for easy adjustment in clinic and has the minor and theoretical advantage that it’s less likely to be exposed through the conjunctiva and damage the corneal endothelium in the longer term.

The recent addition of the ClearPath ST (small tubing) seems to me to be fairly similar to the Paul tube, but potentially quicker to implant.

These changes in tube design have meant a big change for me, as I’ve also had a sevenfold increase in tube operations in 2024-2025, due to various factors. This means patients – such as a young vitrectomised myope or a patient who lives three hours away, or an only-eye needing rapid recovery – in whom previously I might have tried trabeculectomy, seem to be well suited to a tube. While my experience following-up patients with these new tube designs has not been as long as the established track record of Molteno and Baerveldt tubes, it seems to me that exposure of the plate or flow restrictor, troublesome high or low pressures, has been considerably less common. Time will tell whether the risks are indeed lower in the longer term.

Safer, cheaper, faster surgery is a rare thing – most technological advances increase costs and increase work for our eye departments one way or another. It has been striking to me how this change to skinnier tubes has had such an impact on our glaucoma service in Wellington.

References

- Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, Lim LS, Barton K, Goyal S, Ahmed IIK, Brandt JD. Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study (2020). Treatment Outcomes in the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study after 3 Years of Follow-up.Ophthalmology 127(3): 333-345.

- Gedde S, Schiffman JJC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL. Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study (2009). Three-year follow-up of the tube versus trabeculectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol 148(5): 670-684.

- Koh V, Chew P, Triolo G, Lim KS, Barton K and P. G. I. S. Group (2020). Treatment Outcomes Using the PAUL Glaucoma Implant to Control Intraocular Pressure in Eyes with Refractory Glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 3(5): 350-359.

Dr Jesse Gale is a Wellington glaucoma specialist and neuro-ophthalmologist, with roles in private and public hospitals and at the University of Otago Wellington. He is most famous as the 'celestial twin' of Beyoncé, sharing the same birthdate and powerful dance moves.