Scope expansion in Australasia?

The Federal Government of Australia has deferred planned changes to private health insurance coverage for anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections (IVI) in private hospitals and day surgeries, pushing back the change for one year to 1 July 2026.

Originally announced in October 2024, the change would have forced an estimated 12,200 patients, as calculated by Services Australia, to pay for out-of-pocket expenses to access eye injections in private ophthalmology clinics. The move was one of several recommendations made by the Ophthalmology Clinical Committee, chaired by Dr Bradley Horsburgh, for the 2020 Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) Taskforce Review, to save costs.

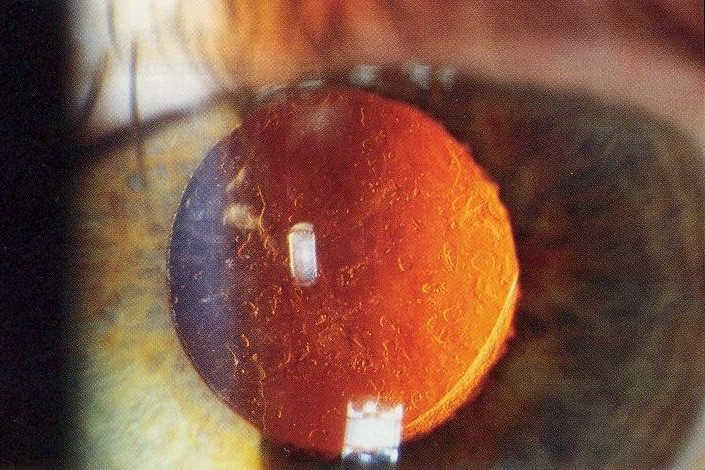

In-hospital IVIs for retinal disease should occur in fewer than 3% of patients but they currently occur in 18% of patients and this number is increasing, said the taskforce in its report. “The committee felt that this is largely unnecessary and may be due to financial incentives.”

The 2020 report noted a large variation in patient treatment frequency in Australia. “The Committee felt that the lowest and highest treatment frequencies may reflect low-value care. MBS data do not stipulate which eye is being treated, which makes it difficult to interpret clinician behaviour and identify low-value care.”

The taskforce also recommended the overall rebate cost for anti-VEGF injections in Australia be reduced and a review be undertaken of the broader ophthalmology workforce to expand the workforce qualified to deliver particular ophthalmology services. “The taskforce recommends a specific focus to assess the expansion of intravitreal injections to include appropriately trained nurse practitioners, optometrists and general practitioners, working to updated guidelines… The primary rationale for this (Recommendation 19) is to increase equitable and timely access to intravitreal injections across Australia, including rural and remote areas.”

Following the report’s publication, there ensued a fierce lobbying campaign by the Macular Disease Foundation of Australia (MDFA) – supported by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) and the Australian Society of Ophthalmologists (ASO) – against the taskforce’s recommendations, which were subsequently ignored until October last year.

When asked about the change of heart, the office of Mark Butler, the Australian minister for health and aged care, confirmed the Australian Government had agreed to the majority of the MBS Taskforce recommendations relating to ophthalmology in the 2024–25 Federal Budget and that these changes were due to take effect on 1 July 2025.

Mark Butler, Australian minister for health and aged care

“There are a number of recommendations that were noted by Government but fall outside the remit of the MBS. Consideration of these recommendations has not been progressed to date but may be considered in due course. This includes Recommendation 19 in relation to reviewing the broader workforce and considering the potential expansion of the registered health practitioner professions that can administer intravitreal eye injection services.”

However, following another bout of lobbying by MDFA, again supported by senior RANZCO and ASO members, the Federal Government said it would defer the reclassification to 1 July 2026 while it undertakes further consultation.

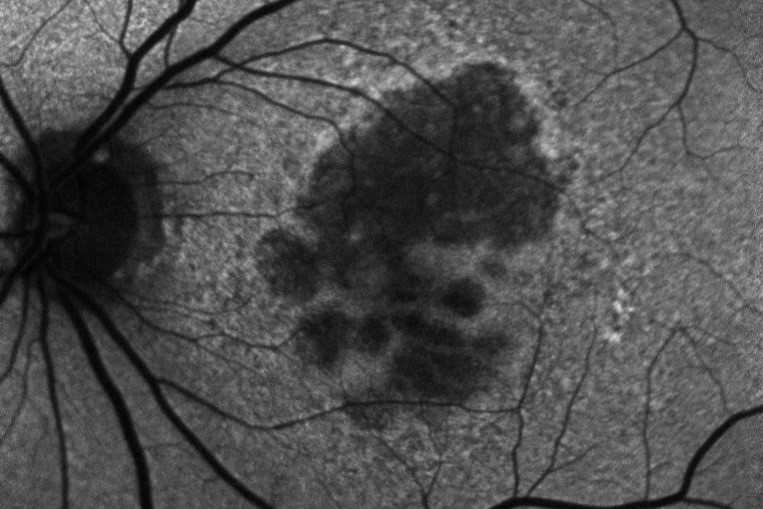

“While MDFA welcomes the Government’s decision to pause this reclassification, it is absolutely vital that the Government addresses the wider affordability issues that continue to be faced by the majority of people requiring sight-saving injections,” said MDFA chief executive Dr Kathy Chapman in a statement. “Importantly, the Government needs to consider that treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is usually frequent (typically every four to six weeks) and lifelong. It’s not a one-off like some other medical treatments, and public eye injection services are either not available or oversubscribed, so for most people the out-of-pocket costs are expensive and ongoing.”

The MDFA said it has been inundated with calls from distressed patients worried about how they’d continue to afford this sight-saving treatment and added that the 12-month deferral to 1 July 2026 is not a solution to the affordability crisis. MDFA research shows patients’ median annual cost for anti-VEGF treatments is NZ$3,955 – approximately 12% of the annual government pension payment – and accounts for 20% of the pension for the almost one in 10 patients who require more frequent treatment. If they’re unable to claim their anti-VEGF treatment under private health insurance, many patients will now have another expense, Dr Chapman told Insight. “MDFA is concerned this will force people to give up their treatment altogether,” she said. A Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee report found close to 50% of Australians reportedly discontinue anti-VEGF treatment within five years, citing cost as the primary barrier.

“Eye injections are primarily delivered in private ophthalmology clinics in Australia, with only around 20% of them offering bulk billing, meaning that more than 72,000 people having eye injections have no choice but to pay expensive out-of-pocket costs to receive their treatment to keep their sight, on top of other costs relating to living with macular disease, such as eye specialist appointments, vision aids and associated travel expenses,” said Dr Chapman.

“It is for these reasons that MDFA is recommending the next Federal Government acts to increase the access to bulk-billed sight-saving eye injections for pensioners… We strongly encourage the Government to make this a key consideration during their planned consultation on the affordability of eye injections.”

To improve access to eye injections for pensioners, the MDFA has proposed an nAMD treatment incentive programme to encourage ophthalmologists to bulk-bill pension-card holders with nAMD. With vision loss estimated to drain the economy of $18.1bn per year, MDFA said the nAMD programme’s $12.1m cost could save the government $153 million annually.

However, with regard to the move to train nurses and other allied health staff in the public system to provide anti-VEGF injections to reduce the cost burden and free-up funds for other serious eye treatments, in a further statement MDFA said, “Intravitreal injections are an important treatment for people with macular disease and should not be underestimated as a minor or simple eyecare procedure. These injections require great skill and experience to be delivered safely. They also need to be delivered in an appropriate clinical environment, with relevant expertise to manage any infection or other treatment-related adverse events.

“Macular Disease Foundation Australia welcomes discussions around models of care and greater industry collaboration that can support more people to access affordable eye injection treatment. Patient safety must be paramount in any new models of care involving non-ophthalmologists delivering eye injections. Learning from the experiences in other countries where the eye-injection workforce has been expanded to include nurses and other allied health professionals is very useful for Australia. The foundation understands that extensive training by, and the supervision from, experienced ophthalmologists have been key to the success of these models.”

When asked to comment on the Australian Government’s move to implement the 2020 taskforce recommendations and subsequent delay, RANZCO’s head of member support Alex Arancibia said the College had no comment.

Optometrists to the rescue?

In March 2025, the Australian Government published Unleashing the Potential of our Health Workforce – Scope of Practice Review, an independent review led by Professor Mark Cormack from the Australian National University College of Health and Medicine examining the barriers and opportunities health practitioners in Australia face working to their full scope of practice in primary care. “A commitment to a more balanced approach to regulating scope of practice, which does not rely solely on title protection, in future legislation and regulation, would help to address the high degree of rigidity within the legislative and regulatory environment,” said the review. “This would help to make the primary care system more responsive to innovation and new evidence which may arise in the future.

This is backed up by the MBS Taskforce report that said the current maldistribution of ophthalmologists affects access for rural and regional patients. “The primary rationale for (Recommendation 19) is to increase equitable and timely access to IVI across Australia, including rural and remote areas.”

Minister Butler said the 2025 review validates the frustrations of so many Australian health professionals. “It tells us that virtually all health professions are held back by restrictions and barriers that are unrelated to their skills, training and experience. Removing these barriers would make it easier for Australians to get high-quality healthcare, when and where they need it, without waiting weeks or driving long distances.”

Also supporting the review’s findings was the industry body Optometry Australia (OA), a long-term advocate for optometry scope expansion in the country. In a statement, it said the review marks a significant and welcome step towards realising OA’s vision of a healthcare system that fully utilises optometrists, working collaboratively with other health professionals, to make a genuine difference in providing timely eyecare for Australians.

An NZ Optics source confirmed at least one nurse, who has been trained to provide anti-VEGF injections in the UK and is now working in Queensland, was providing injections, but the Australian Ophthalmic Nurses Association did not respond to enquiries about this and RANZCO would not comment.

The view from New Zealand

New Zealand has led the way in scope change for nurses and optometrists in ophthalmology. Changes were made to optometrists' scope of practice in 2005 and 2014 to increase the range of therapeutic pharmaceutical agents they could prescribe and, still somewhat controversially, in 2022 to allow specially trained hospital-based optometrists to perform ophthalmic laser surgery. New Zealand nurses also now deliver the bulk of anti-VEGF injections in the public system, run crosslinking, glaucoma and macular degeneration clinics and deliver other minor ophthalmic interventions such as laser.

While more than three-quarters of Australian optometrists are endorsed to prescribe scheduled medicines, OA has struggled to expand their scope of practice further, said Hadyn Treanor, president of the New Zealand Association of Optometrists (NZAO). “Optometry in New Zealand continues to have a wider scope of practice than that in Australia,” he said, noting that the Australian Government is required to approve the recommendations of the Australian optometry regulatory body, the Optometry Board of Australia, which is not the case with the Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians Board (ODOB) in New Zealand.

Where Australia does have a clear advantage is its existing funding model for subsidised eye tests, something that does not exist in New Zealand, he said. “This gives it a significant advantage in using the highly skilled optometry workforce in a true primary healthcare capacity.”

Following the ODOB’s targeted consultation in 2023 on extending hospital optometrists’ scope of practice to include IVI, the NZAO is undertaking the work required to progress the scope expansion for hospital-based optometrists and develop a relevant training programme.

The ODOB is supportive of further expansion to allow New Zealand’s hospital-based optometrists to give anti-VEGF injections, said Suzanne Halpin, ODOB chief executive and registrar. Compared with their Australian counterparts, New Zealand optometrists’ scope of practice has broadened substantially over the past decade, she said. Optometrists in Aotearoa can prescribe any Medsafe-approved medication within their scope of practice; hospital- and ophthalmology clinic-based optometrists are involved in the therapeutic management of patients with systemic conditions including hypertension, diabetes and auto-immune conditions; they can apply for an endorsement to their scope of practice, allowing them to independently manage glaucoma cases (optometrists in Australia cannot do so without collaboration with an ophthalmologist); and suitably trained optometrists can perform minor surgeries, such as the removal of conjunctival concretions and certain types of laser surgeries, she said. “Any change to the regulatory settings in Australia that would make it simpler to align the practice of optometry between Australia and New Zealand would be welcomed by the ODOB,” she added.

With additional reporting by Lesley Springall