Case study: epiretinal membranes and the Govetto classification

Epiretinal membranes (ERMs), also known as macular puckers or cellophane maculopathy, are a relatively common condition affecting the retina, particularly the macular region. These membranes can have a significant impact on a person's vision and quality of life. To better understand and manage ERMs, ophthalmologists and researchers have developed various classification systems, with the Govetto classification being one of the most recent and comprehensive. Such classification offers insight into ERMs’ significance in clinical practice.

Epiretinal membranes are thin, fibrous tissues that form on the inner surface of the retina, particularly over the macula. Since the macula is responsible for sharp, central vision, any disruption in this region is critical. ERMs can develop in one or both eyes and may be idiopathic or secondary to other ocular conditions, including ageing, inflammation, trauma and retinal vascular diseases.

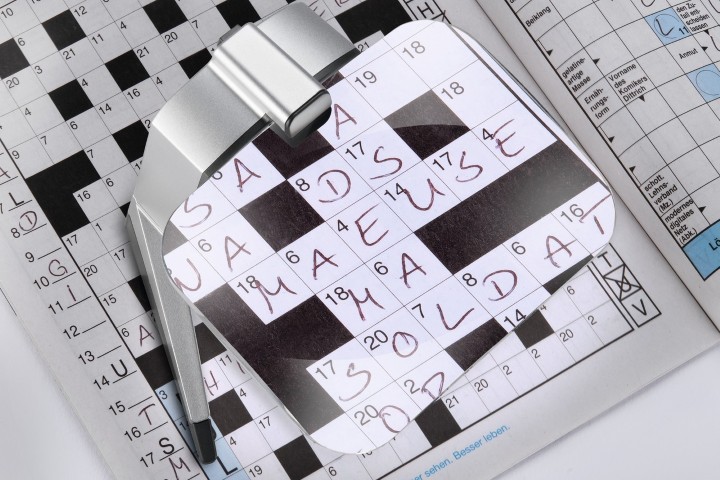

The majority of patients are asymptomatic or mildly troubled by this condition. ERMs do not often progress but if they do, they cause blurry or distorted vision and difficulty reading fine print. They can significantly impair visual function, impacting daily tasks.

Case study

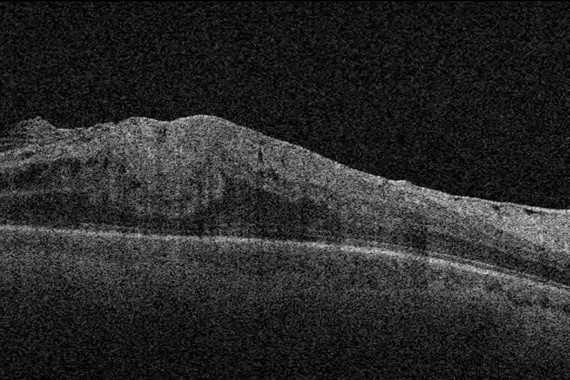

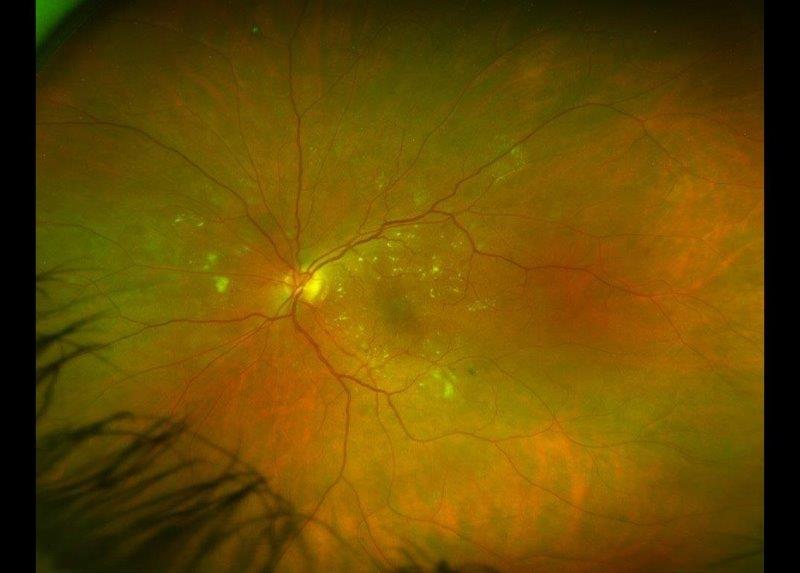

Mrs A, 50 years old, was referred to help improve her vision which had worsened three months after her macula-on retinal detachment repair. She had previously been a high myope who had laser corrective procedure many years ago and lens replacement surgeries nine months prior to presentation. Her best-corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/38 with significant metamorphopsia. The eye was free from any inflammation and her retina was secure. The macula showed a significant epiretinal membrane and macular traction that was highlighted on macular OCT (Fig 1).

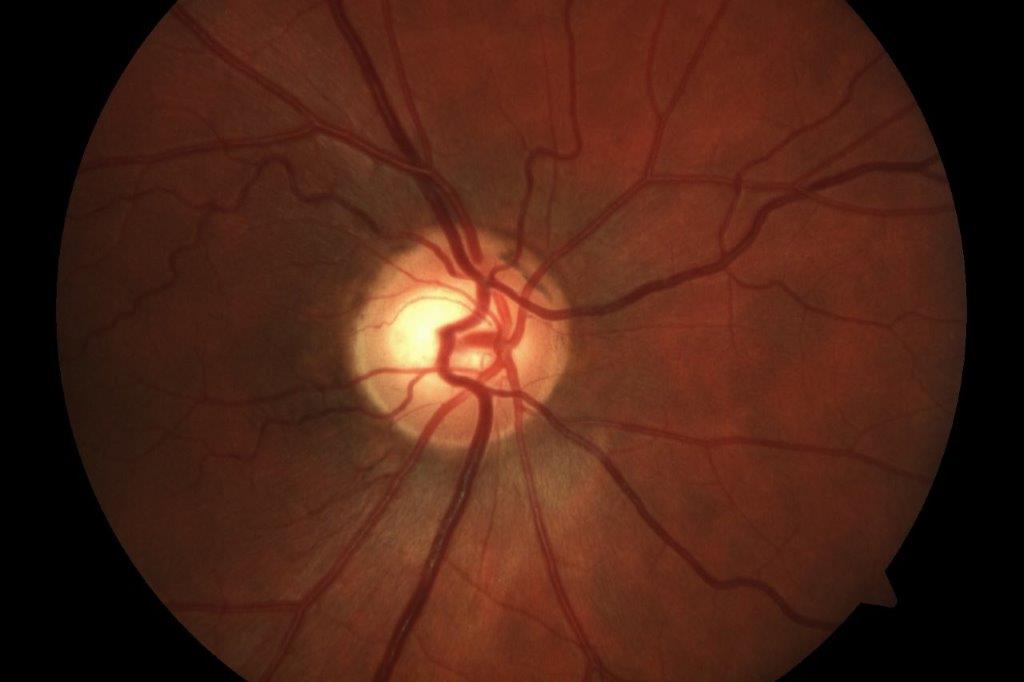

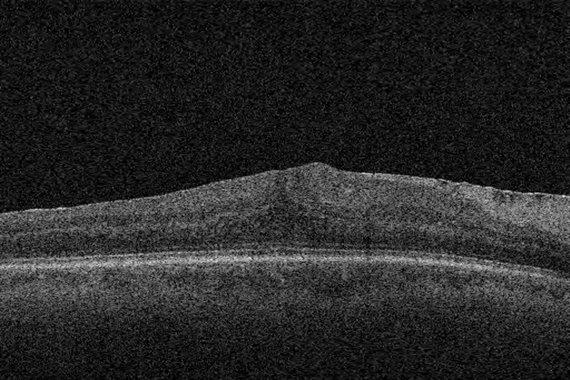

After a thorough discussion of the condition and visual prognosis, we decided to proceed with surgical intervention. She underwent pars plana vitrectomy and epiretinal membrane peel. Two weeks post-surgery, her vision had improved to 6/15, her visual distortion had improved significantly, as had her macular architecture (Fig 2). Further improvement to her visual function is expected, as recovery can take as long as six months.

Fig 2. Post-op OCT showing normalisation of macular layers

ERM classification

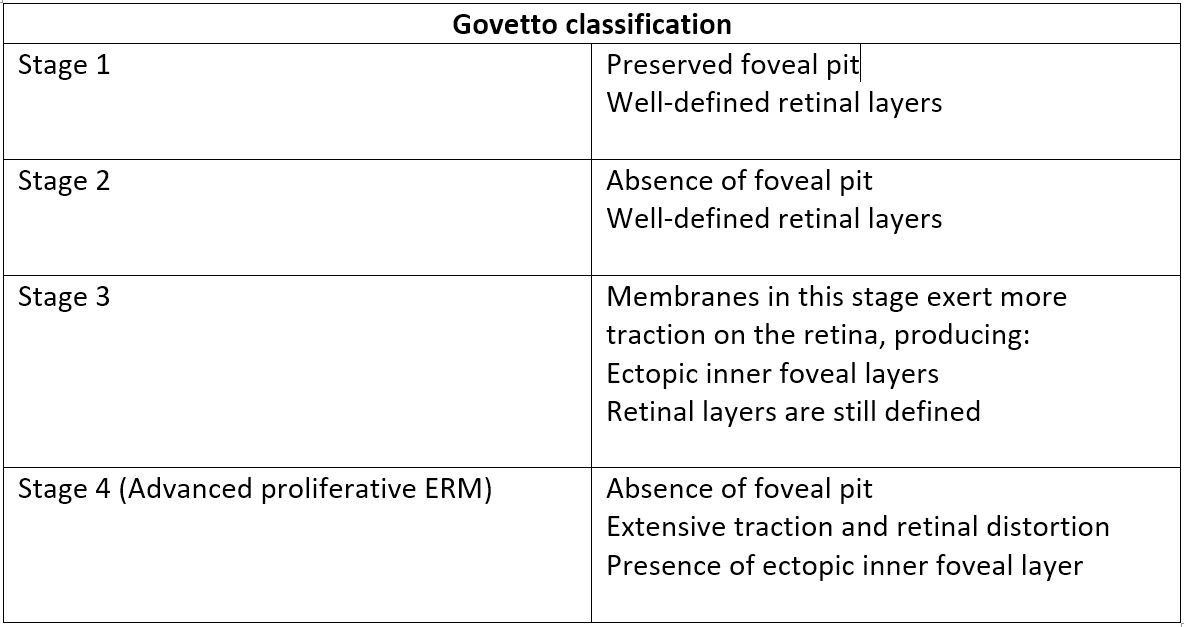

Govetto et al proposed a classification system to categorise ERMs into four distinct subtypes based on their OCT morphology, which aids clinical decision-making and surgical planning. This classification system is a valuable addition to the field of ophthalmology as it recognises the diversity of ERMs and allows treatment to be tailored accordingly.

Table 1. The Govetto ERM classification system

The Govetto classification system provides several advantages for both clinicians and patients. It helps in treatment planning by categorising ERMs into distinct stages, which helps to determine the appropriate treatment approach. Stage 1 and 2 ERMs may not require immediate surgical intervention, while stage 3 and 4 cases are more likely to benefit from surgery. The system also enhances communication between eyecare professionals, allowing them to describe the severity of the ERM in a standardised manner, ensuring clarity and consistency.

Understanding the stage of ERM can also help predict visual outcomes after surgical intervention. Patients with stage 4 ERMs, for instance, may have a less favourable prognosis than those with stage 1 or 2 ERMs. The Govetto classification also facilitates research on ERM management and outcomes, since researchers can analyse data from different stages to refine treatment techniques and improve patient outcomes.

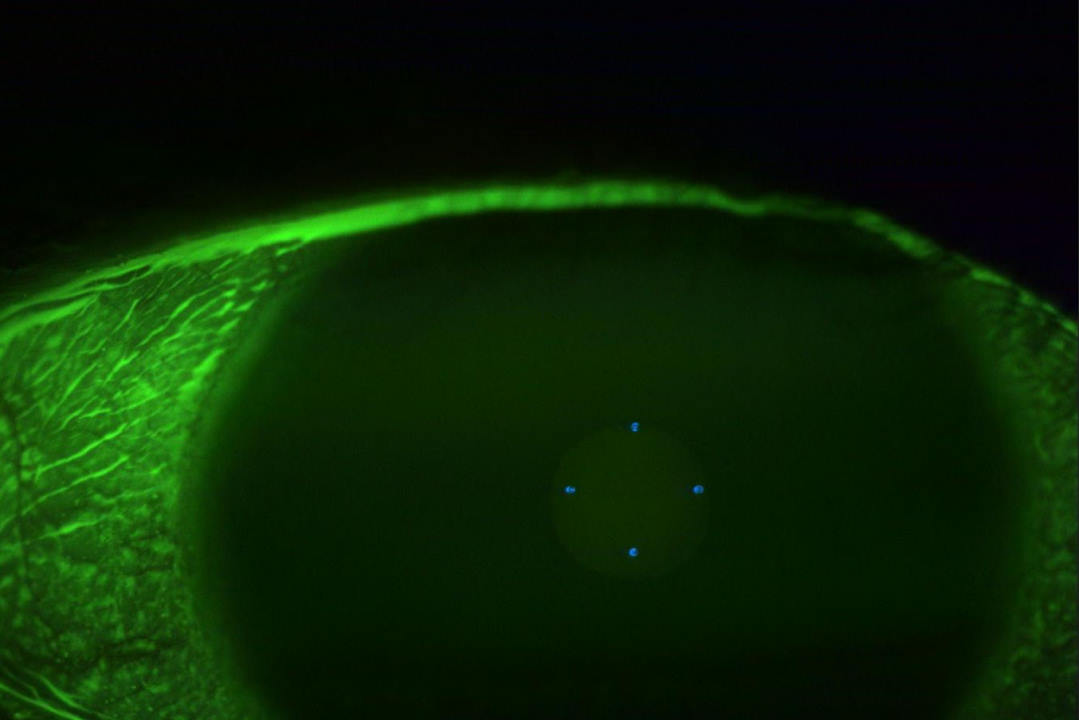

ERM management primarily depends on the severity of the condition and its impact on visual function. In mild cases (stage 1 and some stage 2s) management includes observation – close monitoring without intervention may be appropriate, as visual symptoms might not be significant. For more advanced ERMs (stages 3 and 4), vitrectomy surgery relieves traction on the retina and restores vision by removing the vitreous gel and the ERM. This procedure has evolved over the years with advancements in surgical techniques and instrumentation.

As our understanding of ERMs continues to evolve, ongoing research and innovations in treatment approaches promise improved outcomes for patients. Early detection, accurate classification, and appropriate management are key to preserving and restoring vision in those with ERMs.

Reading list

- Fraser-Bell S, Guzowski M, Rochtchina E, et al. Five-year cumulative incidence and progression of epiretinal membranes: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(1):34-40

- Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T. Wang J, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes. The Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1997; 104: 1033-1040

- Stevenson W, Prospero Ponce C, Agarwal D, Gelman R. Christoforidis J. Epiretinal membrane: optical coherence tomography-based diagnosis and classification. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016; 29: 527-534

- Govetto A, Lalane R, 3rd, Sarraf D, et al. Insights into epiretinal membranes: presence of ectopic inner foveal layers and a new optical coherence tomography staging scheme. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;175:99-113

- Govetto A, Virgili G, Rodriguez F, et al. Functional and anatomical significance of the ecoptic inner foveal layers in eyes with idiopathic epiretinal membranes: surgical results at 12 months. Retina. 2019;39(2):347-357.

Dr Ammar Binsadiq is a New Zealand-trained cataract and vitreoretinal surgeon at Eye Institute and Hamilton Eye Clinic. As a surgeon, he specialises in retinal detachment, epiretinal membranes, macular holes and diabetic retinopathy as well as complex cataract surgeries and secondary lens implantation.