Interventional glaucoma: the future is now

Welcome to the new era of interventional glaucoma (IG)!

Interventional glaucoma – what’s that, you say? These new buzzwords are fast reshaping the management of glaucoma. Having recently attended an international round table meeting with senior glaucoma surgeons to discuss IG, we thought we’d share some of its insights and how we can apply the concept to improve the management of our patients.

IG could easily be confused with minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), which certainly is an important arm of glaucoma management, but the concept of IG is far more encompassing. It is a mindset, an attitude and proactive approach to managing glaucoma that draws on the pillars of early predictive diagnostics, advanced active monitoring and early procedure intervention.

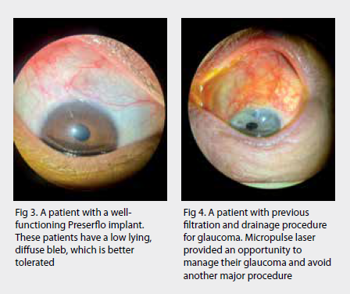

Being proactive means not waiting for significant disease progression before intervening. An IG attitude is not to hope and assume that a patient has fabulous compliance and adherence to their topical medications. Nor does it mean we accept significant ocular surface side effects (that a patient may be unaware of) in the hope of avoiding a procedural intervention.

Key aspects include:

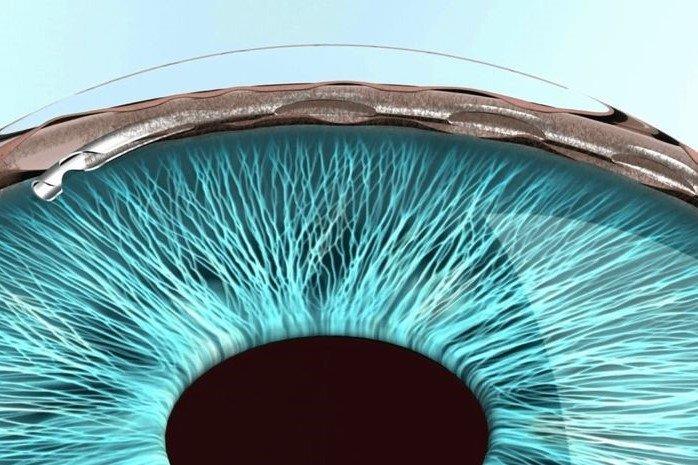

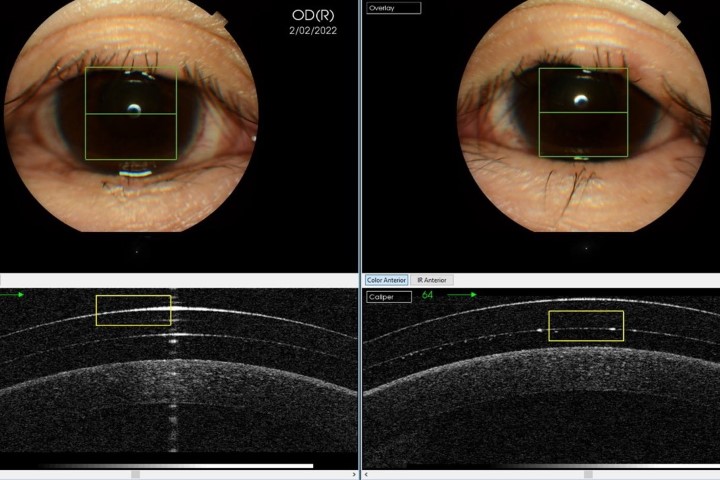

- Early predictive diagnostics – involving early and accurate initial diagnosis with the ability to predict prognosis through analysis of risk factors, ocular biomechanics – intraocular pressure (IOP), optical coherence tomography, accurate visual field (VF) strategies – and genetic testing

- Advanced active monitoring – building on regular, scheduled follow-up visits with robust structural and functional progression analysis, potential new markers for progression (such as detecting apoptotic retinal cells) and more precise data via home monitoring and intraocular sensors

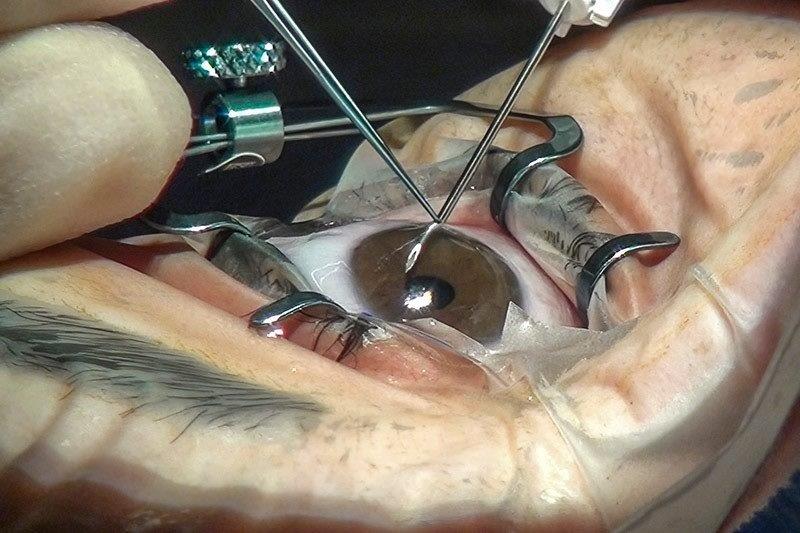

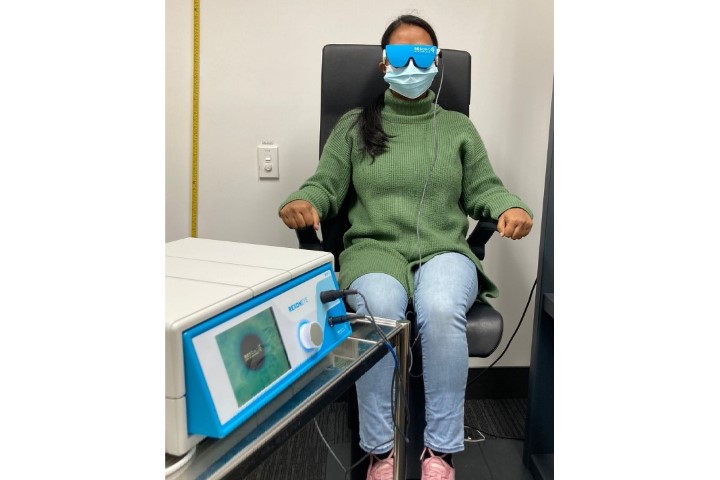

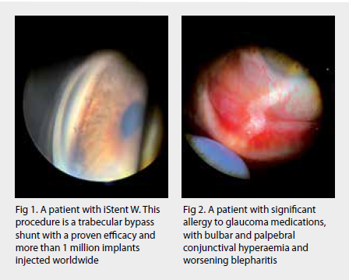

- Early procedural intervention – a mindset shift to eyedrops as a bridging therapy between potentially more definitive therapies including selective laser trabeculoplasty, MIGS (eg. trabecular bypass stents such as iStent), improved drug delivery systems (many are in development), micro-invasive bleb surgery (MIBS) (eg. Preserflo Microshunt) and traditional surgery (eg. trabeculectomy and tube-shunt). Artificial intelligence (AI) will presumably become over-arching in its ability to assimilate these three pillars and help customise our approach to individual patients

IG’s goals and why it’s necessary

Quite simply, IG aims to prevent blindness and improve the overall quality of life of our patients while being cost effective. IG challenges the conventional ‘medication first and always’ approach to achieving these goals.

Landmark studies indicate patients diagnosed and treated with topical medication regimen can suffer significant disease progression1 and that early surgical intervention can slow this more effectively than medical therapy2. Procedural intervention removes compliance issues and is better at smoothing any IOP fluctuations (shown to be associated with significant VF progression in the AGIS study3). Even in those who are compliant with their eyedrops, there is a significant reduction in IOP lowering with each additional class4, with an increase in negative side effects.

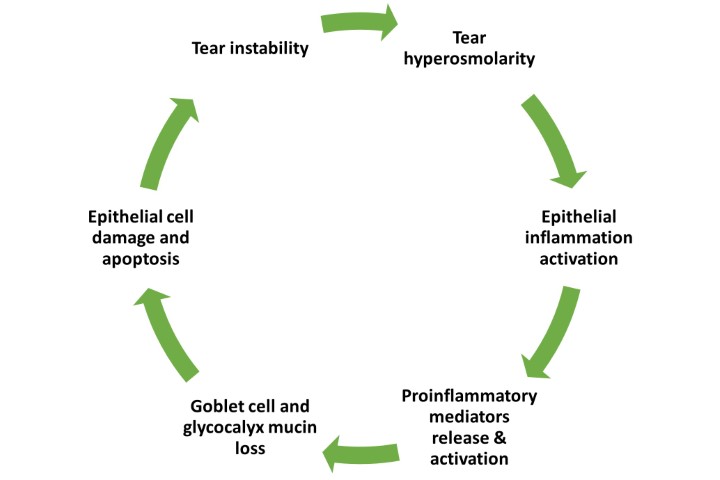

These side effects (including hyperaemia, orbital fat atrophy, ocular surface disease) drive non-compliance, as do forgetfulness, costs, inconvenience, inability to administer drops (arthritis, tremor) and lack of noticeable benefit. Up to 74% of glaucoma patients experience symptoms of ocular surface disease5. The incidence of dry eye disease among glaucoma patients also increases with the number of medications6,7 and is considered a predictor for non-compliance8,9.

In comparison, Schweitzer et al showed that patients at baseline and three months after iStent and iStent Inject implantation had less ocular surface disease10. Samuelson and Singh et al found improvement in both quality of life (VFQ-25 questionnaire) and OSD signs/symptoms in pivotal iStent Inject trial patients up to two years after surgery11. Lau et al showed that nocturnal IOP variability in laser trabeculoplasty is better compared to medication alone12. There is even histopathological evidence proposing increasing trabecular meshwork dysfunction with increasing chronicity of medically treated glaucoma, which suggests early intervention could increase success.

Where to from here?

Adjusting our mindset is the first step in preventing blindness and increasing quality of life for our glaucoma patients. We can use the IG framework to consider the risk profile of our patients to direct the frequency of monitoring. We need to be up to date with the literature to have confidence in the safety and efficacy of early procedural-based glaucoma interventions. We can look forward to technological advances, such as AI, to assist in our decision making and counselling. We should not be accepting of topical medication’s side effects, be suspicious of the utility of stacking multiple medications and consider pulling forward procedural interventions.

MIGS in New Zealand

After more than five years of negotiations, New Zealand’s largest private insurer, Southern Cross Health Society, has added MIGS devices to its members’ policies. MIGS is also funded by most other insurance companies and is available in public hospitals in major centres in New Zealand. The most commonly performed MIGS procedures in Auckland include iStent W, KDB goniotomy, Hydrus, Xen, micropulse and Preserflo. Our local experience with these devices is increasing and more general ophthalmologists are considering these procedures as part of their defence against glaucoma, especially when performed with cataract surgery.

With March marking Glaucoma Awareness Month, it is imperative that MIGS is discussed with all your glaucoma patients to reduce the challenges associated with treating this potentially blinding condition.

Disclosure: This article was independently written by Dr Divya Perumal and Dr Shenton Chew who were sponsored by Glaukos.

References

- Malihi M, Moura Filho E, Hodge D, Sit A. Long-term trends in glaucoma-related blindness in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jan;121(1):134-141. Epub 2013 Oct 25. PMID: 24823760; PMCID: PMC4038428.

- Lichter P, Musch D, Gillespie B, Guire K, Janz N, Wren P, Mills R; CIGTS Study Group. Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001 Nov;108(11):1943-53. PMID: 11713061.

- The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000 Oct;130(4):429-40. PMID: 11024415.

- Jampel H, Chon B, Stamper R, Packer M, Han Y, Nguyen Q, Ianchulev T. Effectiveness of intraocular pressure-lowering medication determined by washout. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr 1;132(4):390-5. PMID: 24481483.

- Mylla Boso A, Gasperi E, Fernandes L, Costa V, Alves M. Impact of ocular surface disease treatment in patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020 Jan 14;14:103-111. PMID: 32021074; PMCID: PMC6969675.

- Rossi G, Tinelli C, Pasinetti G, Milano G, Bianchi P. Dry eye syndrome-related quality of life in glaucoma patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009 Jul-Aug;19(4):572-9. PMID: 19551671.

- Erb C, Gast U, Schremmer D. German register for glaucoma patients with dry eye. I. Basic outcome with respect to dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008 Nov;246(11):1593-601. Epub 2008 Jul 22. PMID: 18648841.

- Baudouin C. Detrimental effect of preservatives in eyedrops: implications for the treatment of glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008 Nov;86(7):716-26. Epub 2008 Jun 3. PMID: 18537937.

- Stringham J, Ashkenazy N, Galor A, Wellik S. Barriers to glaucoma medication compliance among veterans: dry eye symptoms and anxiety disorders. Eye Contact Lens. 2018 Jan;44(1):50-54. PMID: 28181960; PMCID: PMC5500464.

- Schweitzer J, Hauser W, Ibach M, Baartman B, Gollamudi S, Crothers A, Linn J, Berdahl J. Prospective interventional cohort study of ocular surface disease changes in eyes after trabecular micro-bypass stent(s) implantation (iStent or iStent inject) with Phacoemulsification. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020 Dec;9(4):941-953. Epub 2020 Aug 13. PMID: 32789800; PMCID: PMC7708605.

- Samuelson T, Singh I, Williamson B, Falvey H, Lee W, Odom D, McSorley D, Katz L. Quality of life in primary open-angle glaucoma and cataract: an analysis of VFQ-25 and OSDI From the iStent inject pivotal trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Sep;229:220-229. Epub 2021 Mar 15. PMID: 33737036.

- Lau L, Liu C, Chen S, Ko Y, Lee F, Hsu W. Laser trabeculoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2007 Sep;114(9):1790. PMID: 17822985.

Dr Divya Perumal is a New Zealand- and UK-trained ophthalmologist and University of Auckland optometry graduate. Specialising in glaucoma, cataract and pterygium, she consults for Te Whatu Ora and Re:Vision in Auckland.

Dr Shenton Chew is a consultant ophthalmologist at Te Whatu Ora Auckland and Counties Manukau and Auckland Eye. He specialises in cataract surgery and complex glaucoma surgical techniques, including MIGS.