Above and beyond non-invasive breakup time

A central clinical measure in the diagnosis and evaluation of dry eye disease is the tear film breakup time (BUT). Traditionally, its measurement has relied on the instillation of sodium fluorescein and subjective evaluation of the tear film breakup time using the slit lamp biomicroscope. More recently, a shift towards a more noninvasive measure of BUT has enabled more reliable and repeatable measurement of tear film quality and ocular surface integrity. Automated measures of noninvasive breakup time (NIBUT), typically performed using a keratography-based device with infrared illumination, have now become the closest we have to a gold standard method of tear film breakup time measurement.

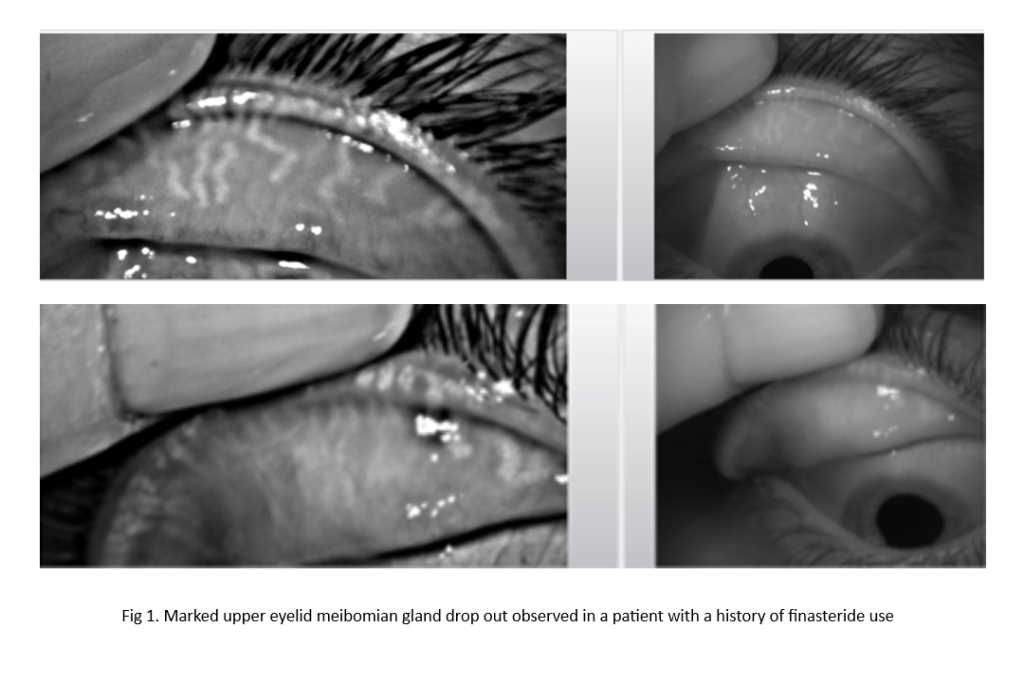

NIBUT is most commonly expressed as the ‘first’ breakup time in seconds, representing the time from the patient’s last blink to the first appearance of an area of localised breakdown of the tear film over the corneal surface. Considering sequential breakup across the ocular surface, this can also be expressed as an ‘average’ breakup time. A commonly used NIBUT measurement device, the Oculus Keratograph 5M, offers additional measures, such as the breakup gradient that represents the acceleration of breakup over time and the extent of the breakup surface area in mm2 (Fig 1). However, these measures are less commonly used and understood in clinical practice.

A new Ocular Surface Laboratory study found that all four values (first, average, gradient and area of breakup) had high diagnostic capability and discriminative ability for dry eye disease1. While all measures were comparable overall, the two most frequently used measures, first and average breakup, were found not to be interchangeable. Interestingly, of all the indices, maximum breakup area provided the highest diagnostic performance.

These findings suggest that dry eye disease is associated with both the extent and the speed of the tear film breakup, alerting clinicians dedicated to using validated measures for the diagnosis and assessment of dry eye disease (such as <10 second being a positive diagnostic marker, as recommended by TFOS DEWS II) to the possibility of other novel measures that might offer improved diagnostic accuracy and consistency in the monitoring of dry eye disease.

Reference

- Speakman S, Wang M, Muntz A, Vidal-Rohr M, Menduni F, Dhallu S, Ipek T, Acar D, Recchioni A, France A, Kingsnorth A, Craig J. Investigating the diagnostic utility of non-invasive tear film stability and breakup parameters: A prospective diagnostic accuracy study. Ocul Surf. 2022 Apr 26;25:72-4.

Dr Alex Müntz is a post-doctoral research fellow with a background in optometry and vision science, working in the Ocular Surface Laboratory at the University of Auckland.