Case study: orbital cellulitis

Severe community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) orbital cellulitis causing permanent visual loss.

Orbital cellulitis is an uncommon but serious ophthalmic emergency that is potentially sight threatening.

In Australasia, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) associated orbital cellulitis was first noted in Brisbane in 20091. Ophthalmic MRSA-associated infection accounts for only 1.3% of all MRSA-associated infection2. One study showed that 89% of preseptal cellulitis Staphyloccous aureus isolates are MRSA3. MRSA-associated orbital cellulitis is clinically more severe and may progress rapidly causing severe ophthalmic sequelae.

Here, we highlight a recent case of MRSA-associated orbital cellulitis complicated with severe visual loss.

The case

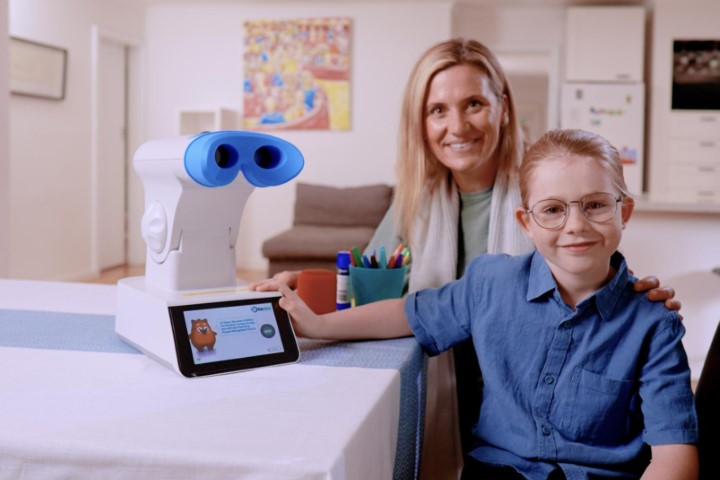

A 15-year-old Australian male was on a holiday cruise ship when he presented with a sudden onset of rapid left-sided periorbital swelling and erythema. On first consultation with the cruise ship doctor, the patient was treated with topical chloramphenicol. His symptoms worsened within four hours and the left eye was completely shut as a result of the periorbital tissue swelling. A provisional diagnosis of periorbital cellulitis was made. He was immediately given intravenous ceftriaxone 1g stat. He received a second dose of the same antibiotic 12 hours later, but his clinical status worsened (see Fig 1).

Fig 1. Left-sided peri-orbital swelling from underlying MRSA-associated orbital cellulitis in this case

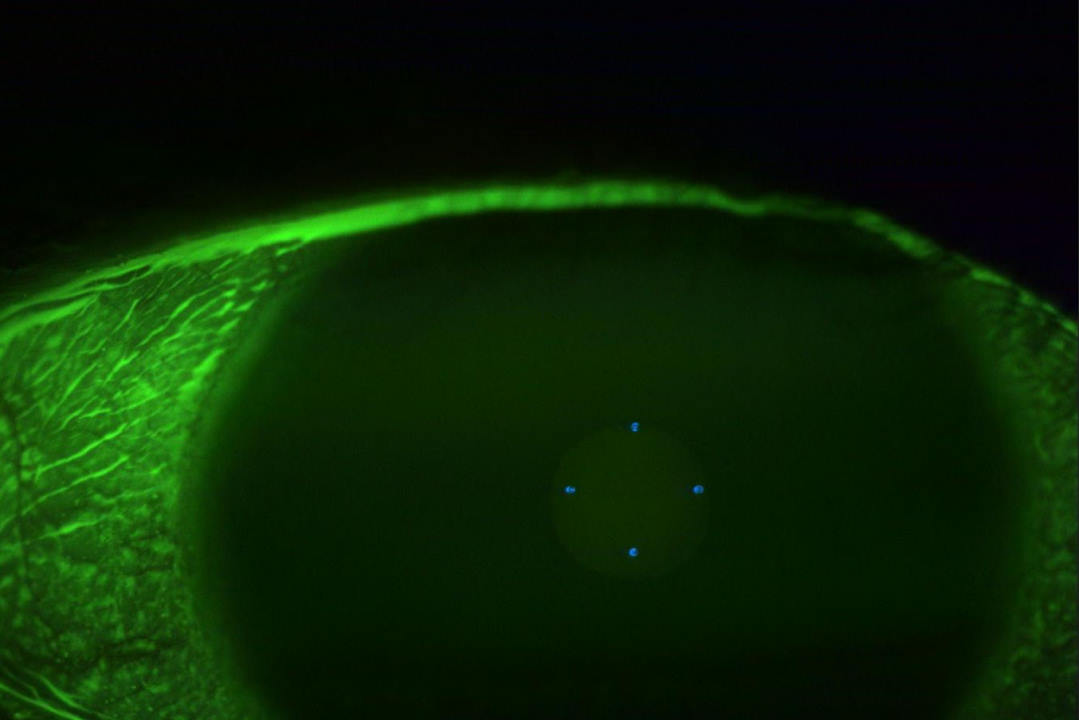

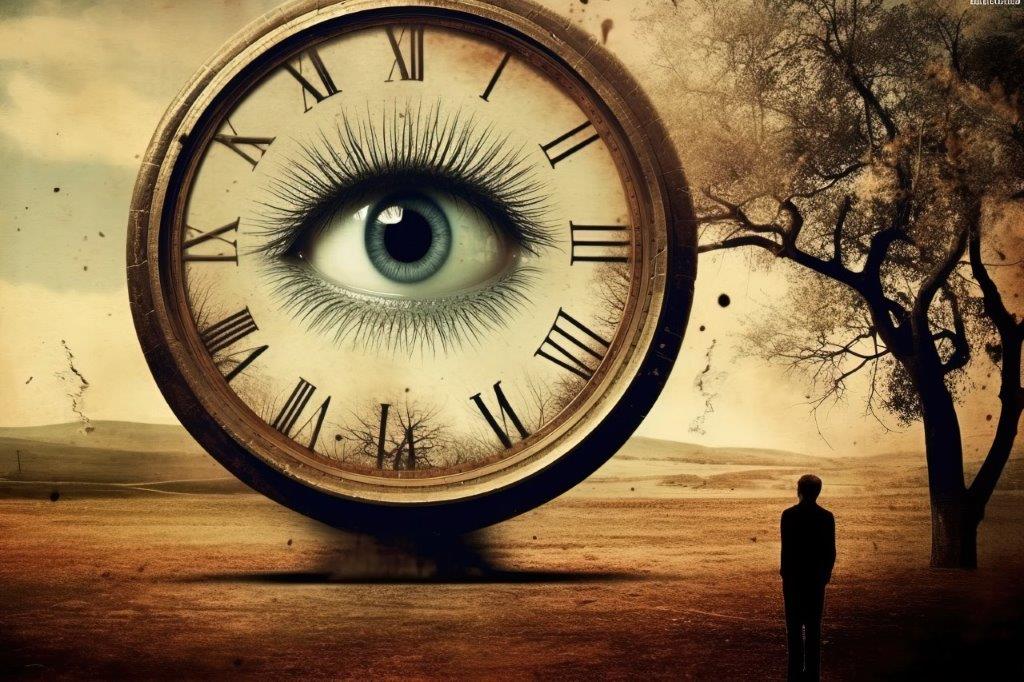

The cruise ship docked at a port in New Zealand the next morning and the patient was transferred to a tertiary hospital. Initial assessment showed he had no light perception in the affected eye and his pupil appeared dilated and not responsive to light stimuli. The hospital emergency department organised an urgent computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbit and head which showed a left-sided orbital cellulitis with sub-periosteal abscess on the medial wall of the orbit with significant obstructive sinus disease (see Fig 2).

Fig 2. Left-sided MRSA-associated orbital cellulitis in a 15-year-old male. CT scan of the orbit in (A) coronal section and (B) axial section, and (C) D) MRI scan of the orbit in coronal section

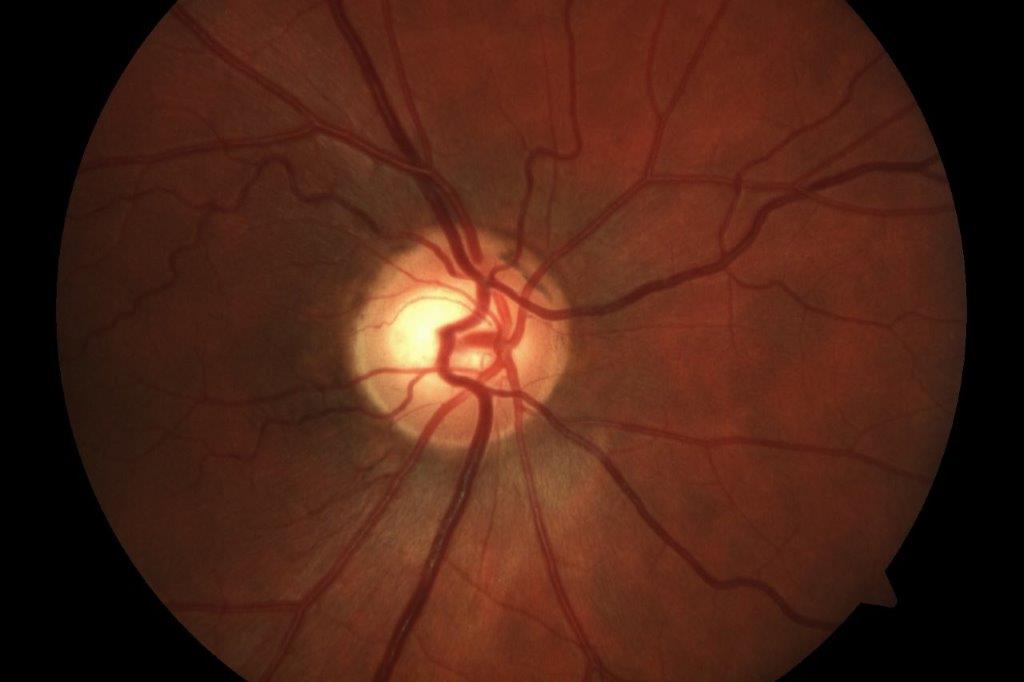

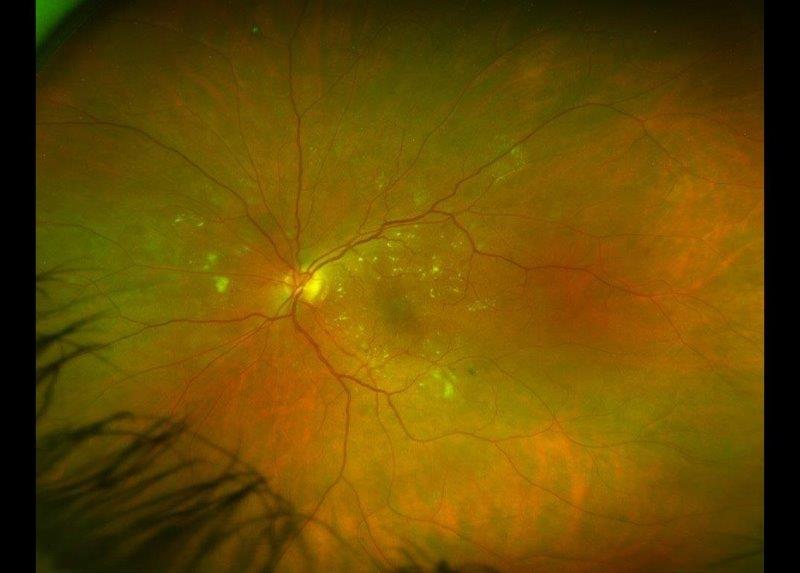

The ophthalmology on-call team was notified and an immediate lateral canthotomy and cantholysis was performed to relieve the orbital compartment syndrome. Despite the procedure, his vision remained at no light perception with an obvious relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). The otolaryngology team was consulted and performed an endoscopic anterior ethmoidectomy and drainage of abscess under general anaesthesia. An immediate relief of periorbital swelling was noticeable and the intraocular pressure came down from 29mmHg to 14mmHg. However, his vision remained at no light perception. He then commenced intravenous ceftriaxone and flucoxacillin but clinically deteriorated 48 hours later. He had a complete sinus washout and anterior ethmoid-frontal sinus trephine and drainage of abscess. The pus culture grew Queensland strain MRSA and his anti-microbial therapy was switched to linezolid orally with ongoing intravenous ceftriaxone. Despite the prompt surgical and medical treatment, the vision of the patient’s affected eye remained at no light perception.

Comment

Prior to the 1990s, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) was historically one of the pathogens most commonly associated with orbital cellulitis and periorbital cellulitis. The incidence of Haemophilus influenzae-associated infection declined significantly with the introduction of the Hib vaccine. Currently, Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis, and S. pyogenes account for approximately 75% of paediatric periorbital cellulitis4. A separate report from Houston, Texas, examining the microbiology of paediatric orbital cellulitis and sinusitis, found that MRSA represented 73% of all S. aureus isolates5.

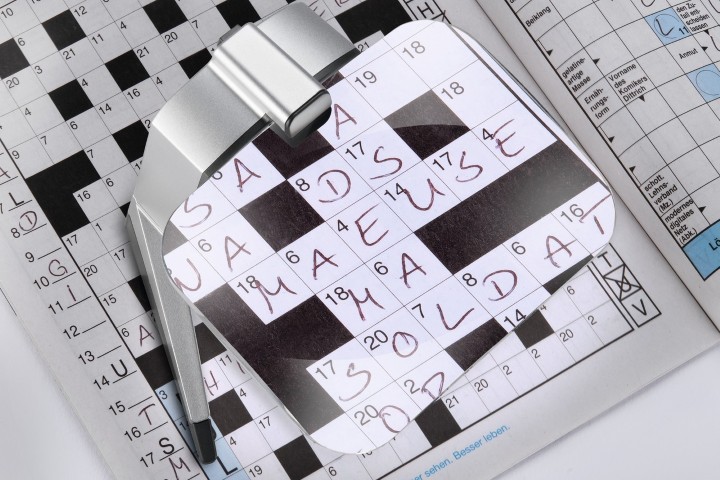

Evidence suggests that MRSA-associated periorbital and orbital cellulitis is on the rise. MRSA-associated orbital cellulitis is well-known for its rapid and severe progression. The severity of the clinical outcome of this reported case could have been reduced or avoided if a few clinical practices were introduced earlier. Firstly, visual acuity and pupillary examination are vital in differentiating a preseptal periorbital cellulitis from an orbital cellulitis. This was not documented in the initial care of the patient on the cruise ship. In the setting of an evident optic neuropathy or orbital compartment syndrome, an emergency lateral canthotomy and cantholysis should have been performed immediately. As the patient is from Queensland, Australia, where community-acquired MRSA is highly prevalent, early empirical treatment for MRSA-associated infection should have commenced sooner. Suspected MRSA orbital cellulitis should be promptly treated with intravenous vancomycin and a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as linezolid. Early surgical drainage of focal abscesses also plays an important part of the treatment regimen6. For community-acquired MRSA-associated preseptal periorbital cellulitis, oral antibiotic remains appropriate if the infection is considered mild to moderate. The recommended regimens include clindamycin 450mg TDS, minocycline 100mg BD, co-trimoxazole 960mg BD as loading dose then continuing with 960mg OD or Linezolid 600mg BD plus rifampicin 300mg BD for 5 days6. All cases of suspected retro-bulbar or orbital involvement will require prompt hospital admission and CT orbit imaging.

References

- Vaska VL, Grimwood K, Gole G, et al. Community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Causing Orbital Cellulitis in Australian Children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011; 30:11, 1003-1006

- Blomquist PH. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections of the eye and orbit (An American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Transactions of the American Ophthalmology Society. 2006;104, 322-345

- Witherspoon SR, Blomquist PH. The Changing Microbiologic Spectrum of Preseptal and Orbital Cellulitis: Emergence of Methicilin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47,3970

- Bottling AM, McIntosh D, Mahadevan M. Paediatric pre- and post-septal peri-orbtial infections are different diseases. A retrospective review of 262 cases. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2008; 72(30), 377 - 383

- McKinley SH, Yen MT, Miller AM, et al. Microbiology of pediatric orbital cellulitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;144(4), 497-501

- Weiner G. MRSA Ophthalmic Infection, Part 2: Focus on Orbital Cellulits. EyeNet Magazine, American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2013. Accessed 25th February 2018. Available from https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/mrsa-ophthalmic-infection-part-2-focus-on-orbital-

Dr Sheng Chiong Hong, MB BCh BAO, ophthalmology registrar, Dr Louisa Joyce Lim, MB BCh BAO, radiology registrar, and Dr Casey Ung, MBBS, consultant ophthalmologist, are based at Dunedin Public Hospital, New Zealand.