CASE STUDY: Spontaneous reattachment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments

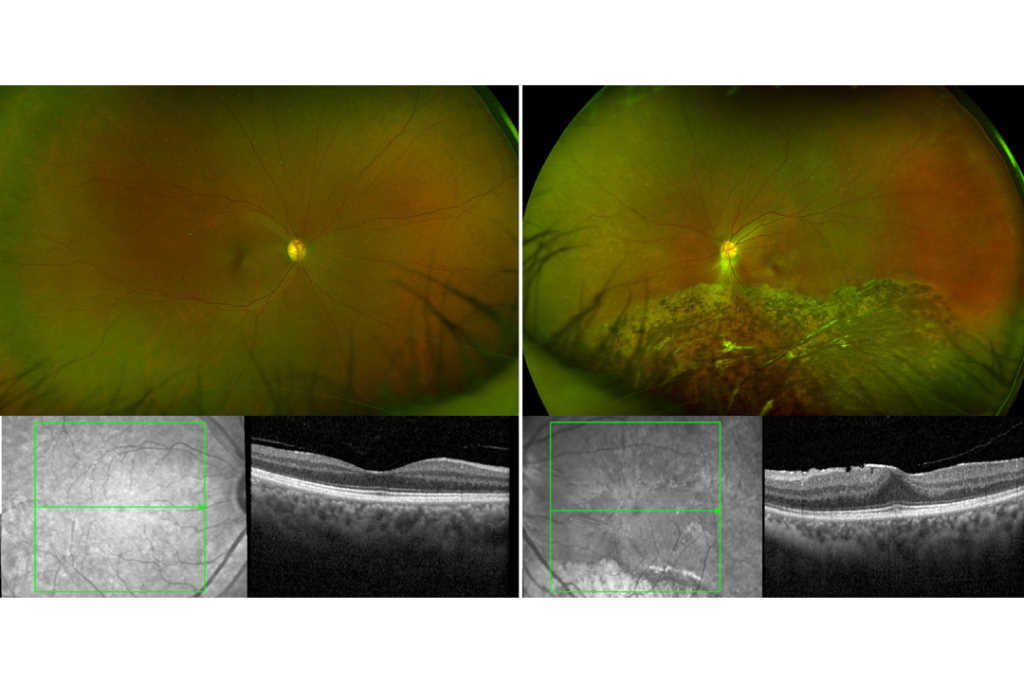

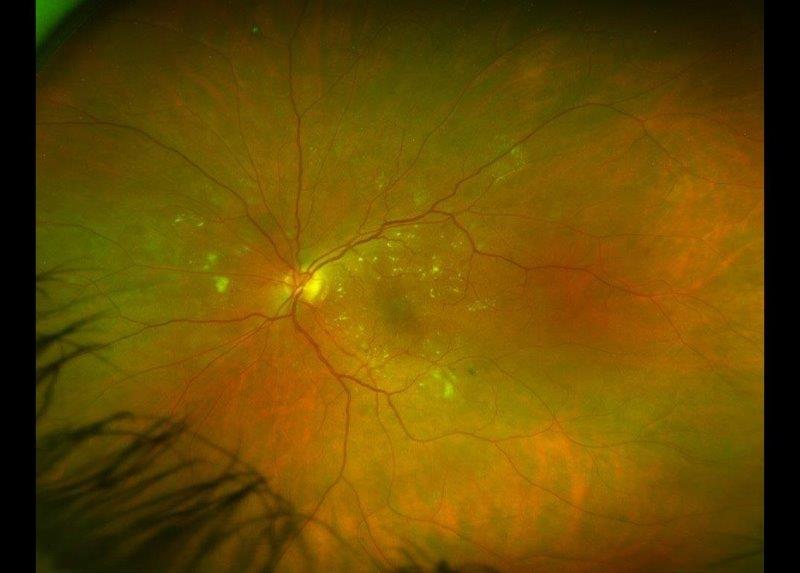

Case 1: Mrs B is a 55-year-old woman who was referred by her optometrist with suspected retinitis pigmentosa. She had no known ocular, systemic or family history of significance. On examination, her best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6/6 on the right (plano/-0.25x85) and 6/7.5 on the left (plano/-1.25x10). Her anterior segments appeared healthy and her intraocular pressures were normal. Her wide-field fundus photographs and macular OCT scans (Fig 1) showed inferior pigmentary changes, as well as a moderate epiretinal membrane in her left eye. Indented peripheral retinal examination showed trace inferior subretinal fluid but no signs of a retinal break.

Spontaneous reattachment of a left rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was suspected. She was observed over the next two years and her examination findings remained stable. Prophylactic barrier laser treatment was subsequently performed around the inferior subretinal fluid in her left eye.

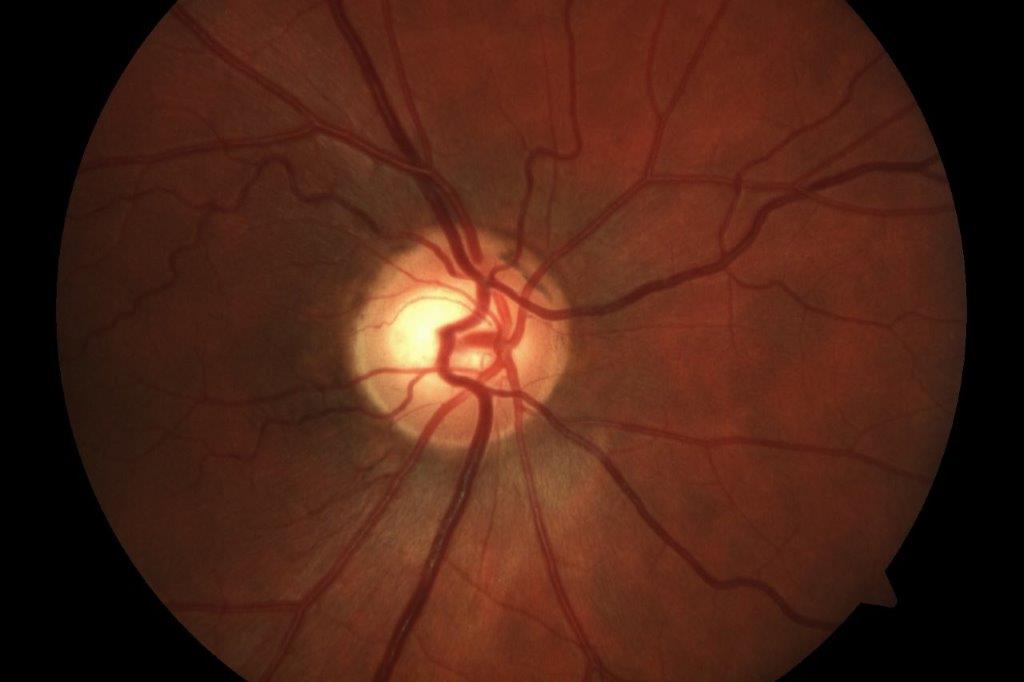

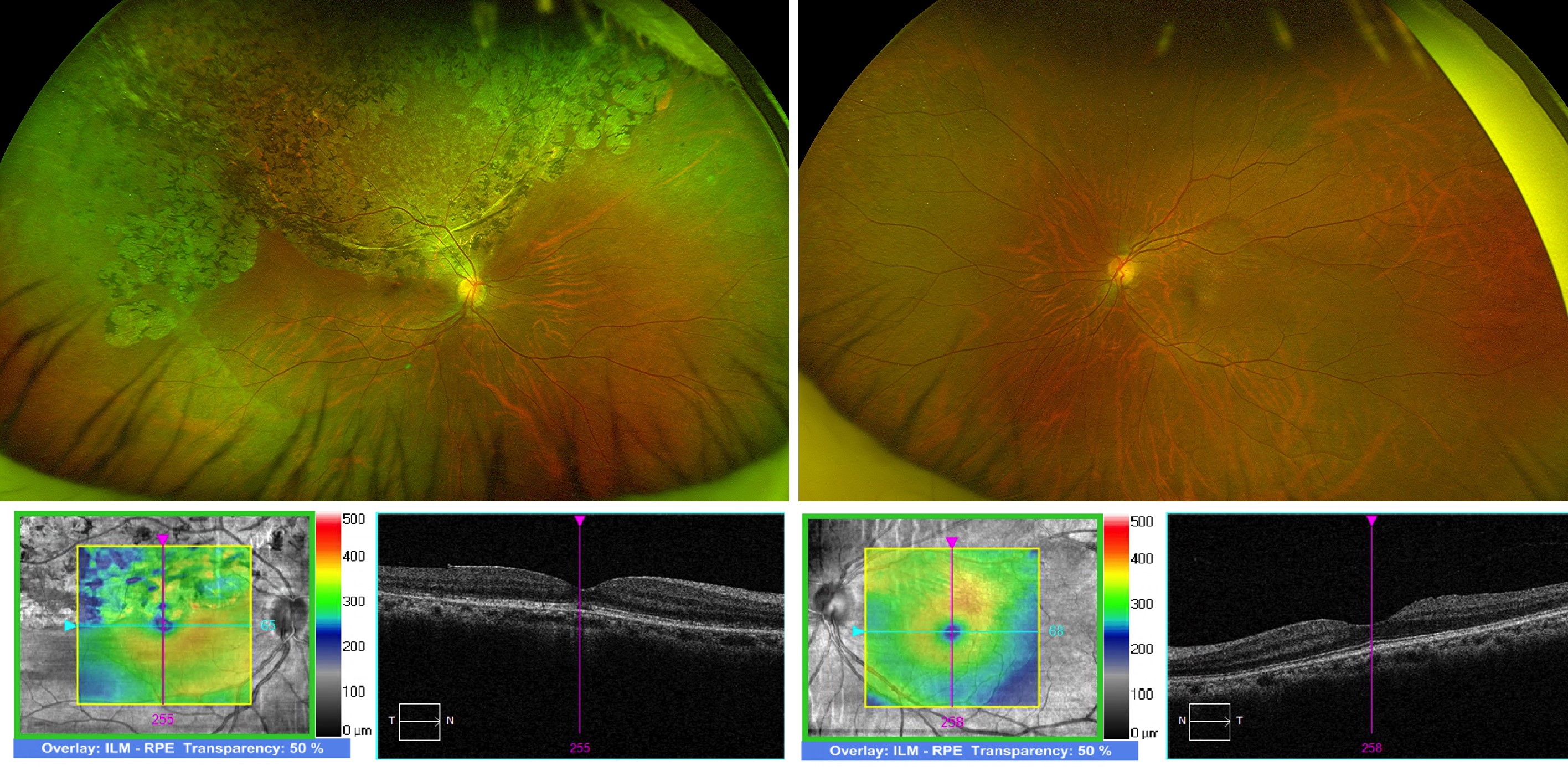

Case 2: Mrs Y, a 56-year-old woman, was referred by her general practitioner with loss of her right inferior visual field, which she noticed while playing with her children. She had no other ocular symptoms, nor any significant past medical or ocular history. On examination, her BCVA was 6/12 on the right (-3.75/-1.25x57) and 6/6 on the left (-5.75/-0.50x52). Her anterior segments and intraocular pressures were normal. There were no signs of any ocular inflammation. Funduscopy revealed right superior retinal pigmentary and atrophic changes (Fig 2). She had a right superotemporal peripheral retinal hole, without any accompanying subretinal fluid.

Fig 2. Bilateral, wide-field fundus photographs and macular OCT scans, documenting right superior retinal atrophic and pigmentary changes, extending to the fovea

Like case 1, spontaneous reattachment of a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was suspected and barrier laser treatment was performed around her right superotemporal retinal hole, following discussion of the associated risks and benefits. Mrs Y’s examination findings remained stable three months following her laser treatment.

Discussion

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments are caused by a hole or tear in the retina, which allows fluid to pass through and detach the retina. They are generally progressive and require surgical intervention. Spontaneous reattachment of a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (SRRRD) is a rare phenomenon and was initially described in 19811.

The largest case series to date analysed 15 consecutive patients with SRRRD2. Like Mrs B and Mrs Y, all 15 involved eyes had unilateral diffuse retinal pigmentary alterations within a sharply demarcated and convex margin. The mean age of their patients was 48 years and the inferior retina was affected in two thirds of cases. Interestingly, a retinal defect within an area of SRRRD was detected in only one of the 15 patients.

With these two cases, one has to assume that both Mrs B and Mrs Y had prior asymptomatic rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. One natural history study estimated that the prevalence of asymptomatic retinal breaks in the population (over the age of 10) was approximately 5.8% and, within this group, the prevalence of asymptomatic retinal detachments was 8.5%.3 This means that asymptomatic retinal detachments are found in approximately one in every 200 people (over 10 years old). Fortunately, they are not aware of its presence, not unless detected by routine funduscopy. The rate of progression to a symptomatic retinal detachment was found to be equal to the likelihood of spontaneous regression, 11%. Also, myopic females were found to be 4.7 times more likely than males to develop an asymptomatic retinal detachment.

Pigmentary changes of the retina can occur in many other retinal conditions, including resolved chronic exudative retinal detachments secondary to optic disc pits, colobomas, central serous chorioretinopathy or posterior uveitis. Hence, one should look closely for anatomical defects or signs of active ocular inflammation in these patients, such as retinal vascular sheathing, anterior chamber or vitreous cells, retinitis or retinal haemorrhages. Inherited retinal dystrophies should also be considered. However, the retinal pigmentary changes in these patients are commonly bilateral, diffuse and symmetrical. Resolved retinitis sclopetaria from high velocity ocular trauma can also cause sector retinal pigmentary changes.

Based on their case series with ophthalmic ultrasound imaging, one research group theorised the development mechanisms of SRRRD4. Initially, focal vitreoretinal adhesion and traction induce a peripheral retinal break in an eye without a complete posterior vitreous detachment. This is followed by an influx of liquefied vitreous into the retinal break, causing a localised retinal detachment. However, the attached posterior vitreous limits this detachment and the direction of vitreoretinal traction becomes parallel to the elevated retinal surface. Eventually, the vitreoretinal traction is relieved and the retinal break is closed by vitreous fibres running parallel to the retinal plane. A thin membrane proliferates over the retinal break from glial and retinal pigment epithelial cell hyperplasia and the fluid current through the retinal break is interrupted. Subretinal fluid is gradually resorbed, causing the clinical appearance of SRRRD.

In summary, SRRRD should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with unilateral sectoral retinal pigmentary changes within a sharply demarcated convex margin. The retinal abnormalities in these patients should remain stable and their fellow eye should be examined carefully.

References

1. Cantrill HL. Spontaneous retinal reattachment. Retina 1981; 1:216 –9.

2. Cho HY, Chung SE, Kim JI, et al. Spontaneous reattachment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Ophthalmology 2007;114:581-6.

3. Byer NE. Subclinical retinal detachment resulting from asymptomatic retinal breaks: prognosis for progression and regression. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1499–503.

4. Chung SE, Kang SW, Yi CH. A Developmental Mechanism of Spontaneous Reattachment in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Korean J Ophthalmol 2012;26(2):135-138

Dr Joel Yap is a consultant ophthalmologist specialising in retinal diseases and vitreoretinal surgery, with a particular interest in clinical research and secondary intraocular lens implantation. He’s based at Eye Institute, Eye Doctors, Auckland District Health Board and Counties Manukau District Health Board in Auckland.