CASE STUDY: The importance of spotting microtremors

A 52-year-old South-East Asian female presented to clinic for a routine eye exam. She had been experiencing some near blur and a constant gritty sensation in both eyes; otherwise, she had no notable symptoms. Her last medical exam was six months prior and she had hypercholesterolaemia that was under control with Crestor. Otherwise, her general health was quite good.

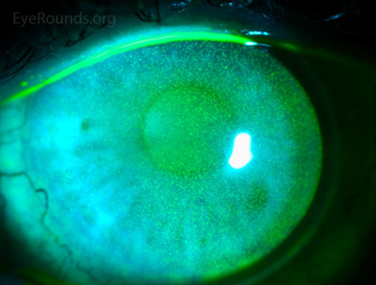

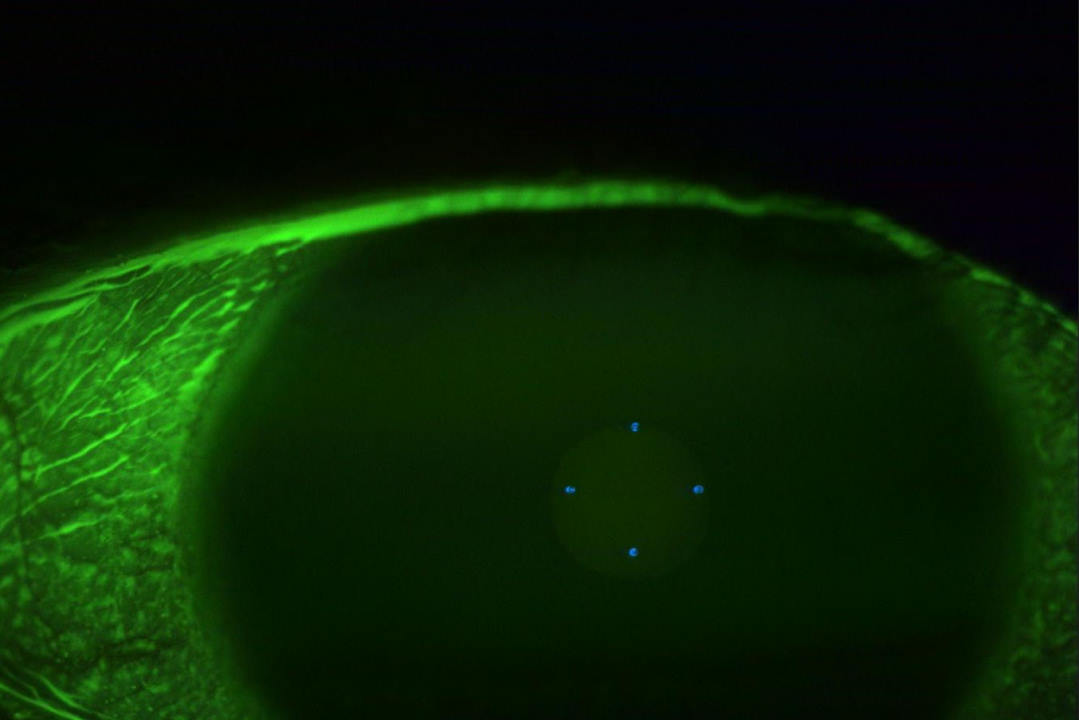

Her pupil reactions were unremarkable – confrontational fields were full in both eyes and her best corrected visual acuity was 6/7.5+1 in the right eye, 6/6-2 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination showed a similar presentation to Fig 1 in both eyes. There was some meibomian gland dysfunction with gland drop out, lid wiper epitheliopathy and a visibly incomplete blink.

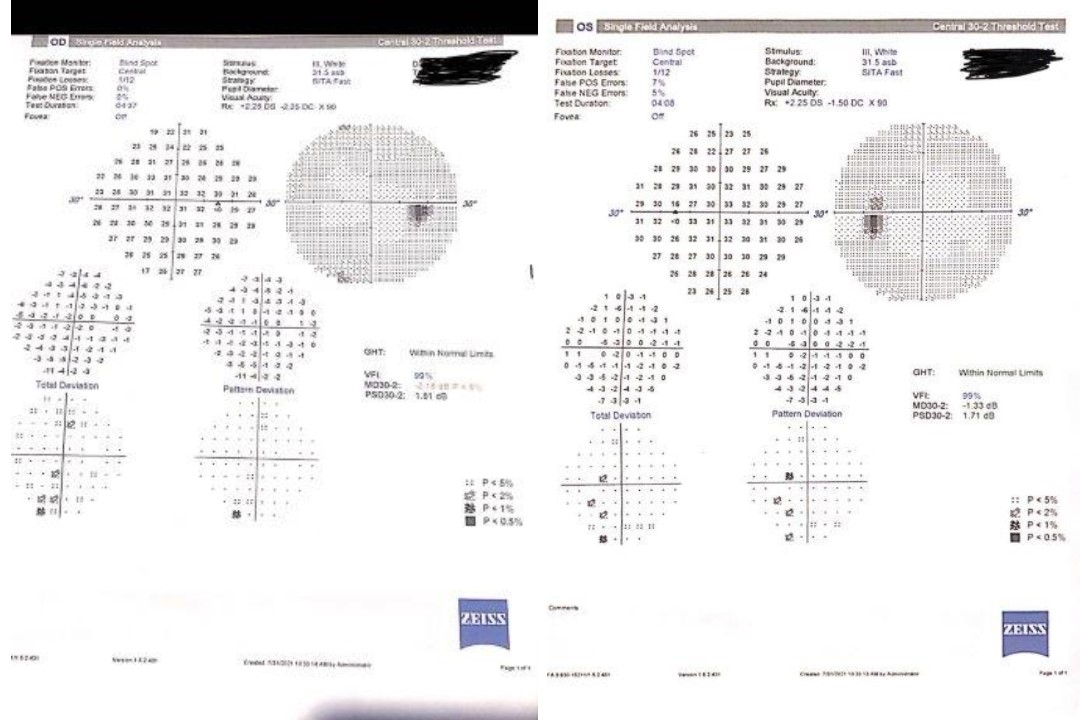

Anterior chamber was quiet, inferior van Herick was 0.2 in both eyes and there was early nuclear sclerosis in each eye. Dilated fundus examination showed healthy-looking macula, vasculature and unremarkable peripheral retina. Cup:disc ratio was 0.4, with neuroretinal rim intact in each eye; right optic nerve was slightly tilted. Red cap test was 100% in the right eye, 90% in the left. 30-2 results were as per Figs 2a and 2b below.

Fig 2a. 30-2 results and Fig 2b. 30-2 results

What’s the diagnosis?

A case like this requires an entrance test that is often skipped by optometrists: fixation and extraocular motilities testing.

- Clinical pearl 1: pay attention to motilities!

This patient had unstable fixation and an observable tremor with her extraocular motilities. A microtremor is not always observable to the naked eye (often it requires specialised eye tracking instrumentation) and is best seen when you slow down with your motilities testing and hold your fixation stick stable for a couple of seconds a few times throughout your ‘double H’ test. It is a high frequency, low amplitude physiological tremor of the eyes that is present even when the eye is at rest1.

Why is this relevant?

A microtremor has been demonstrated to have a very strong link to Parkinson’s disease (PD), a neurodegenerative disease where damage occurs to dopamine-producing neurons. Symptoms include dementia, depression, tremors, loss of small or fine hand movements, problems with balance or walking, and aches and pains.

The amplitude and the gaze direction of the microtremor observed are independent of the severity of Parkinson’s or duration of disease, which means that even in cases of early Parkinson’s there can be an observable or measurable microtremor2. Other potential ocular motility deficits include square-wave jerks – small saccades that affect fixation.

- Clinical pearl 2: PD patients often present with a triad of symptoms

Patients with Parkinson’s have been found to have a reduced blink amplitude, eyelid retraction and reduced blink rate. Reduced blink amplitude has also been linked to computer use, so make sure to get an idea of your patient’s estimated screen use to help with your differential diagnoses. The reduced blink rate in PD is hypothesised to be related to neurotrophic effects on the cornea, so you can include a cotton-bud test to screen for your patient’s corneal sensitivity. This screening is most effective when you perform it routinely on a wide sample of patients, improving your ability to gauge atypical or reduced corneal sensitivity.

Another finding we can anticipate to accompany significant ocular surface issues and resultant punctate epithelial erosions is a reduced visual acuity (VA) in patients with PD. Even more likely is a reporting of fluctuating vision by the patient. Sometimes they can find this quite debilitating, especially in the context of their existing mobility issues.

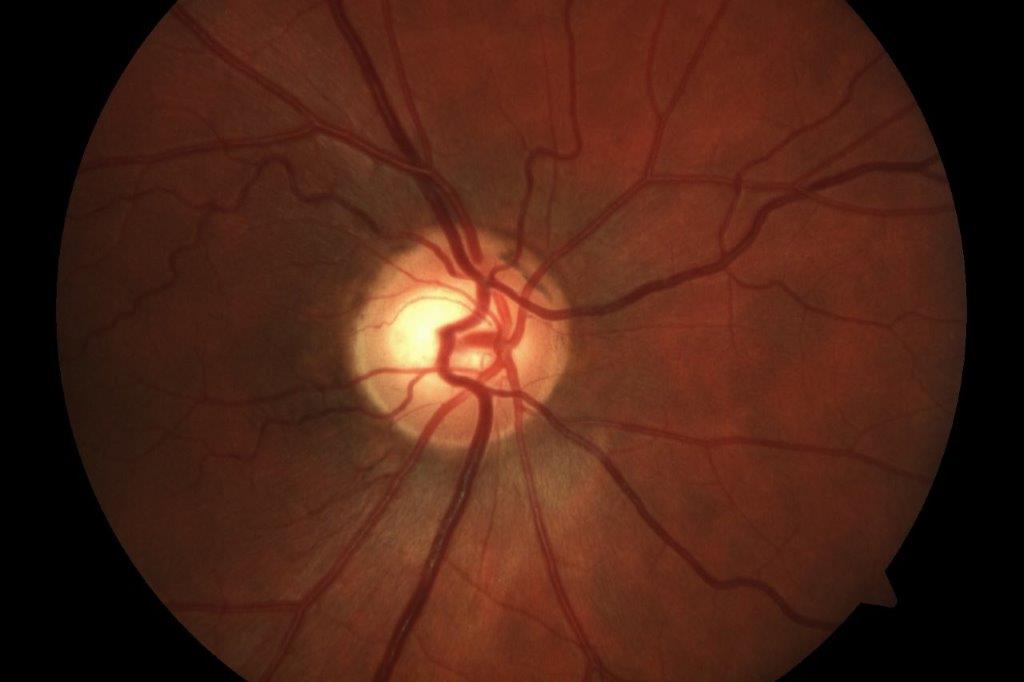

There has been a lot of discussion about retinal biomarkers with respect to PD. Studies have shown that reduced macular thickness is not as reliable a biomarker as evaluating the thickness of segmented OCT layers such as the inner nuclear, inner plexiform, outer nuclear and especially the ganglion cell layer. This thinning has been demonstrated to be related to loss of dopaminergic cells3,4, so enhanced depth imaging OCT has some utility. One study showed that ganglion cell layer thickness was inversely correlated with PD severity and duration5.

Other papers have shown retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) loss to be correlated with PD6. The take-home is that there is no consensus on OCT biomarkers and not to look at them in isolation7. When you see some unexplained RNFL or ganglion cell thinning, consider your differential diagnoses and remember the triad, paying attention to the motilities and ocular surface findings.

- Clinical pearl 3: PD is linked to glaucoma and convergence insufficiency

Contributing to the lack of consensus on retinal biomarkers is the fact that PD patients can have glaucoma concurrently. This means that your PD patient will require a thorough glaucoma work up (including central corneal thickness, gonioscopy, etc) and reliable OCT scans free of artefacts, especially because their visual field testing might not be a true reflection of what they see due to their resultant dexterity issues from PD. This leads us to our next pearl…

- Clinical pearl 4: patients often overlook their tremor

PD symptoms are exacerbated by stress and anxiousness, so often patients will dismiss their ‘nervous tremor’ as not noteworthy. So, as soon as you notice the aforementioned triad, make sure you ask about symptoms of tremor, including when your patient is upset. You can also consider a screening ‘paper test’ where you rest a paper on the back of your patient’s outstretched hand and observe for movement of the paper. The paper will make the tremors more visible; however, please note this is just a screening test and has many limitations.

Another idea is to ask about the general symptoms associated with PD. These include uncontrollable shaking and tremors, but also extend to speech changes, handwriting changes, postural and balance issues, slowed movement (bradykinesia), rigid muscles and autonomic dysfunction. This particular patient identified her handwriting changes and even noticed that she had begun typing her documentation at work more often as a subconscious adaptation.

- Clinical pearl 6: PD is a diagnosis by exclusion

Upon observing the triad, especially if your patient is symptomatic, it is a good idea to refer them to a GP or neurologist. PD is a diagnosis by exclusion – the healthcare practitioner will assess your patient’s symptoms and whether medications improve their symptoms. A neurologist can also perform a DaTscan to measure dopamine as part of the diagnostic process. In the case of my patient, she was prescribed Sinemet and her symptoms improved.

References

- Bolger C, Bojanic S, Sheahan N, et al Ocular microtremor (OMT): a new neurophysiological approach to multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2000;68:639-642

- Gitchel GT, Wetzel PA, Baron MS. Pervasive ocular tremor in patients with Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2012 Apr 9

- Chorostecki J, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Shah A, et al. Characterization of retinal architecture in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2015;355(1-2):44-8

- Ahn J, Lee JY, Kim TW, et al. Retinal thinning associates with nigral dopaminergic loss in de novo Parkinson disease. Neurology. August 15, 2018

- Garcia-Martin E, Larrosa JM, Polo V, Satue M, Marques ML, Alarcia R, Seral M, Fuertes I, Otin S, Pablo LE. Distribution of retinal layer atrophy in patients with Parkinson disease and association with disease severity and duration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Feb;157(2):470-478

- Inzelberg R, Ramirez JA, Nisipeanu P, Ophir A. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in Parkinson disease. Vision Research. 2004;44(24):2793-7

- Kaur M, Saxena R, Singh D, et al. Correlation between structural and functional retinal changes in Parkinson disease. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2015;35(3):254-8.

Bahija al Wandawi (left)

This article is dedicated to the loving memory of Layal's inspirational grandmother (bebe) Bahija al Wandawi who battled with Parkinson’s disease until her death in February this year.

Australia-based optometrist Layal Naji is a lecturer of optometry at the University of Canberra and co-founder of the outreach optometry clinic at the Asylum Seekers Centre in Newtown, Sydney.