Conquering the diagnostic dilemma of Acanthamoeba keratitis

Acanthamoeba is a free-living protozoan mainly found in water and soil. Like other protozoa, it exists as a motile, feeding trophozoite which when in danger turns into a cyst (Fig 1). The cystic form is double walled and resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation and antimicrobial agents. Although Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) accounts for less than 1% of all infective keratitis overseas, the incidence in New Zealand has been on the rise. This is thought to be primarily due to the increasing use of contact lenses, which account for more than 95% of cases. Interestingly, in India, less than 1% of Acanthamoeba keratitis is contact lens related, which is explained by the low prevalence of contact lens wear and the widespread use of contaminated water in the country’s rural areas.

Since bacteria and viruses account for the majority of cases of infective keratitis, a diagnosis of AK is often made as a relation to a non-healing corneal ulcer. Given its relative rarity in New Zealand, considering Acanthamoeba as the causal agent of infective keratitis cases is often delayed, which leads to less favourable outcomes. A proactive approach is certainly needed to achieve better outcomes.

Fig 1. Acanthamoeba as visualised by direct microscopy;

A: Acanthamoeba cyst, B: Trophozoite. (Image adopted

from Boggild et al, J Clin Microbiol 2009)

Diagnosing AK

Following a systematic approach is critical in diagnosing AK. The process typically involves good history taking, careful examination, establishing differential diagnoses and ordering the correct investigations.

History

In taking a history from patients presenting with keratitis, it is important to ask about risk factors such as contact lens wear and contact lens hygiene. Poor contact lens hygiene specifically related to AK includes: cleaning contact lenses with tap water, washing eyes with contaminated water, or swimming with contact lenses in situ, particularly in hot pools. The typical patient is a young person who uses extended-wear contact lenses and does not maintain good lens hygiene. Although less common, we have also treated patients with AK in New Zealand who were not contact lens wearers.

AK patients often present with eye pain, redness and photophobia that has been present for a few weeks. The pain in advanced stages can be very severe and out of proportion to the examination findings. This is due to keratoneuritis, an inflammatory response of the corneal nerves.

AK is often misdiagnosed early on as viral keratitis or less commonly as bacterial or fungal keratitis. Therefore, it is important to consider Acanthamoeba in any patient whose keratitis is unresponsive to treatment.

Examination

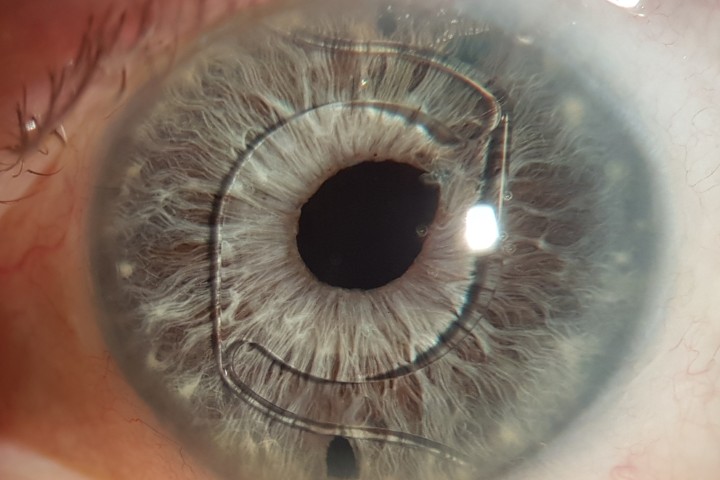

Acanthamoeba initially infects the epithelial layer and progressively invades the superficial and deep stroma. Very rarely, AK progresses to endothelial keratitis. The epithelial disease is characterised by granular whorls or cystic changes. Early appearances can take the shape of pseudodendrites (Fig 2), but lesions do not uniformly uptake fluorescein unless there is frank ulceration. AK epithelial disease makes the epithelium very fragile, which can slough off as a whole sheet, thus confusing the diagnosis with viral geographical ulcers or recurrent corneal erosion. Left untreated, Acanthamoeba will penetrate deeper into the stroma, giving rise to non-specific stromal opacification (Fig 3), multiple infiltrates or the more classical pictures of radial keratoneuritis (Fig 4) or a ring infiltrate (Fig 5). Once in the deep stroma, Acanthamoeba becomes challenging to eliminate. Endothelial disease is very rare but has been reported in the literature, which adds to the complexity of diagnosis.

Fig 2. A 35-year-old patient with a penetrating corneal

transplant and current contact lens wear. Note the

epithelial granularity, with epithelial microcysts in a

pseudodendrite pattern (arrow). Non-specific anterior

stromal opacification is also noted (arrowhead)

Fig 4. Acanthamoeba keratitis with marked radial

keratoneuritis (arrows)

Fig 5. Advanced corneal disease with ring infiltrate in

Acanthamoeba keratitis

Investigations

Investigations are used to support clinical suspicion and help differentiate diseases. There are several modalities available to diagnose AK. These are often used together to complement and support the diagnosis of AK.

- Microbiological testing: smear microscopy and cultures are still regarded by many as the gold standard definitive investigation for diagnosing AK. The Acanthamoeba cysts stain with calcofluor stain, Giemsa and KOH. Acanthamoeba is also cultured using a non-nutrient agar seeded with Coli. The trophozoites feed on the E. Coli leaving ‘snail tracks.’ Nevertheless, diagnosing AK through microbiological testing is very dependent on the volume and quality of the specimen that reaches the lab. Where possible, additional microbiological testing of the contact lens and case is advised.

- Molecular testing: PCR amplification of Acanthamoeba DNA has been utilised for many years to assist with diagnosing AK and has a sensitivity of more than 85%; however, PCR testing for Acanthamoeba is not available in all areas of New Zealand. Recent advances include immunofluorescent monoclonal antibodies to detect Acanthamoeba, the results of which are encouraging.

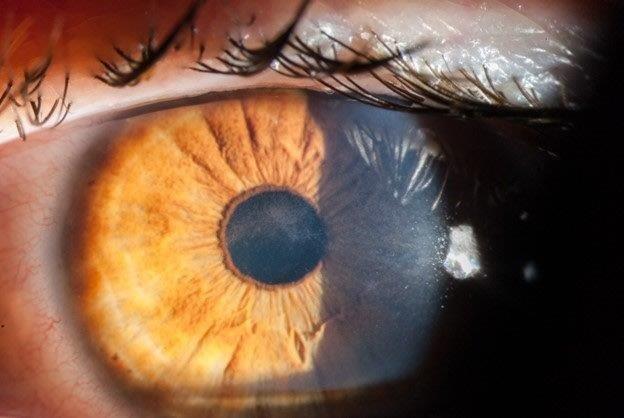

- In vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM): IVCM has revolutionised the diagnosis of AK. It is able to image histological sections of the cornea as thin as 2-4μm with sensitivity and specificity of more than 85% in a good operator’s hands. The IVCM principle is based on eliminating all out-of-focus images using a diffraction-limited spot or slit. In AK, IVCM can identify the amoebic cysts which appear as round hyperreflective bodies, occasionally even discerning the double-walled cysts (Fig 6). The trophozoites are more difficult to identify since they can appear similar to dendritic cells or keratocytes. Since cultures are low yield in AK, IVCM is emerging as a key investigation for AK for its accuracy and fast results.

Fig 6. In-vivo confocal microscopy image taken from a patient with Acanthamoeba keratitis showing numerous Acanthamoeba cysts, some of which show the classical double walled appearance (arrow)

Treatment

Hospital care is often required. The treatment involves intensive dual anti-amoebic therapy in the form of polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB 0.02%) or chlorhexidine 0.02% along with propamidine isetionate (Brolene). Topical treatment initially is intense (instilled hourly for 48-72h) and is then slowly tapered down over the course of several weeks to cessation over 6-12 months. Since Acanthamoeba can remain in the cystic form for months to years, AK can rebound while tapering or after cessation of treatment and thus patients require close monitoring. The prognosis is poor when the Acanthamoeba penetrates deep into the corneal stroma as eradication is often difficult with antimicrobials. Even if eradication is successful, the resultant corneal scarring may warrant corneal transplantation.

Conclusion

Due to the increasing popularity of using contact lenses for refractive or cosmetic purposes, the incidence of AK is increasing both in New Zealand and worldwide. Considering Acanthamoeba in the differential diagnosis of contact lens related keratitis is crucial. A proactive approach is needed and the diagnosis is reached through thorough history taking, careful examination and appropriate investigations. An early diagnosis is pertinent for a timely cure and a good visual outcome.

For more, see: https://eyeonoptics.co.nz/articles/archive/contact-lens-related-keratitis-in-new-zealand/

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Professor Charles McGhee for his support in writing this article and providing key images.

Bibliography

- McKelvie J, Alshiakhi M, Ziaei M, Patel DV, McGhee CN. The rising tide of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Auckland, New Zealand: a 7-year review of presentation, diagnosis and outcomes (2009-2016). Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018 Aug;46(6):600-607.

- Patel DV, Rayner S, McGhee CN. Resurgence of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Auckland, New Zealand: a 7-year review of presentation and outcomes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan;38(1):15-20;

- Niederer RL, McGhee CN. Clinical in vivo confocal microscopy of the human cornea in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010 Jan;29(1):30-58.

- Patel DV, McGhee CN. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a comprehensive photographic reference of common and uncommon signs. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009 Mar;37(2):232-8.

- Pandita A, Murphy C. Microbial keratitis in Waikato, New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Jul 2011;39(5):393-7.

- Vaddavalli PK, Garg P, Sharma S, Sangwan VS, Rao GN, Thomas R. Role of Confocal Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Fungal and Acanthamoeba Ophthalmology. 2011;118(1):29-35.

- Weber-Lima MM, Prado-Costa B, Becker-Finco A, et al. Acanthamoeba monoclonal antibody against a CPA2 transporter: a promising molecular tool for acanthamoebiasis diagnosis and encystment study. Parasitology. 2020;147(14):1678-1688.

- Lalitha P, Lin CC, Srinivasan M, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis in South India: a longitudinal analysis of epidemics. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. Apr 2012;19(2):111-5.

Dr Haitham Al Mahrouqi and Dr Corina Chilibeck are both based at the Department of Ophthalmology, which is headed by Professor Charles McGhee at the University of Auckland. Dr Al Mahrouqi is a senior fellow in cornea and anterior segment, with a keen interest in keratoconus, while Dr Chilibeck is the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel corneal and anterior segment clinical research fellow. Her doctoral studies focus on cataract surgery, surgical risk and surgical training, including the Eyesi Surgical simulator.