AMD – sometimes it’s the simple things

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of blindness, contributing to about 50% of all blindness in New Zealand. It is estimated that 1 in 7 people over the age of 50 will be affected by macular degeneration. The disease can not only result in devastating visual loss for untreated patients but can also come with significant socioeconomic impact, with the total cost of vision loss from AMD in New Zealand estimated to be $391 million in 20161. With an increasingly ageing population, the burden of AMD is set to increase.

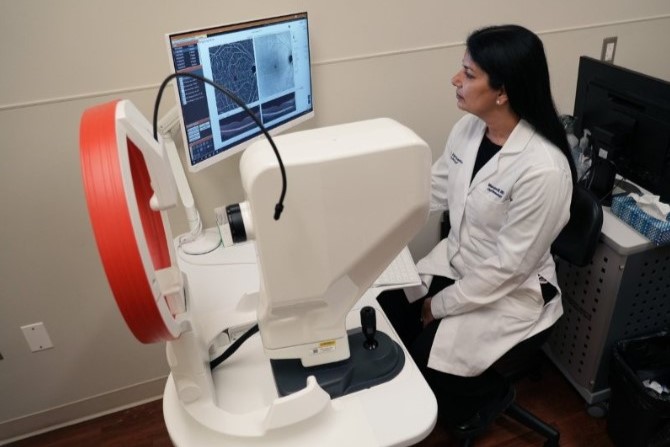

A degenerative process affecting the macula, AMD signs can often be found in the early stages during ophthalmic fundal screening procedures and as part of incidental posterior pole findings. Typically, patients remain asymptomatic until late AMD, which may begin to impair central vision.

Using the Beckman classification, one can define AMD’s stages.

Beckman classification2 of AMD

Normal ageing changes

- Only small drusen (<63µm) present

- No AMD pigmentary abnormalities (defined as any definite hyper- or hypopigmentary abnormalities associated with drusen)

Early AMD

- Medium-sized drusen (63-125µm)

- No AMD pigmentary abnormalities present. For reference, 125µm is the average width of the retinal veins at the optic disc margin

Intermediate AMD

- Large drusen (>125µm), or medium drusen in addition to AMD pigmentary changes

Late AMD

- Either geographic atrophy or choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM, also known as wet AMD) present

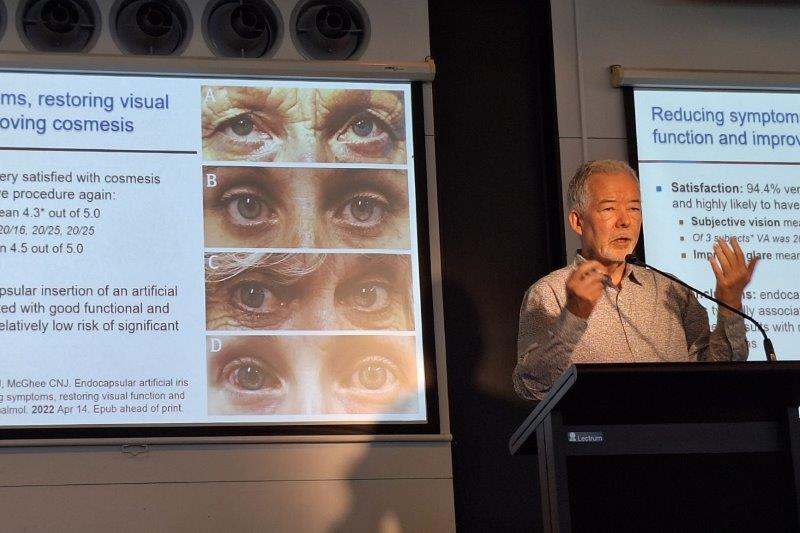

In the current age of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatments, good outcomes can be achieved for wet AMD with early diagnosis and treatment. With Pharmac funding, our current first-line treatment options remain bevacizumab (Avastin), with aflibercept (Eylea) and ranibizumab (Lucentis) available if certain criteria are met. There is certainly anticipation around the newly developed but as-yet-unavailable faricimab (Vabysmo), which is a dual-action monoclonal antibody inhibiting both the anti-VEGF and angiopoietin-2 pathways, which may be able to maintain treatment efficacy out to 16-week intervals.3

While the clinician keeps busy determining best injection treatment plans for our wet AMD patients – as well as the need for injection-only clinics to relieve health service demand – doctor-patient consultations can become fewer in between. When we do have the opportunity to see our patients, one must not forget the multilateral approaches we have to improve their ocular health. From an AMD perspective, it can be easy to focus on the treatment response of the fluctuating subretinal fluid above the CNVM of one eye and be glad the other eye ‘still only’ has dry AMD with some large drusen and pigment change. In such a scenario, it may be worthwhile to recall that established risk calculation tables3 are available that would give this patient the highest risk factor score of 4 and a five-year risk of progression to late AMD of around 53%.

Table 1. Calculation of AMD risk-factor scores

Can we do more?

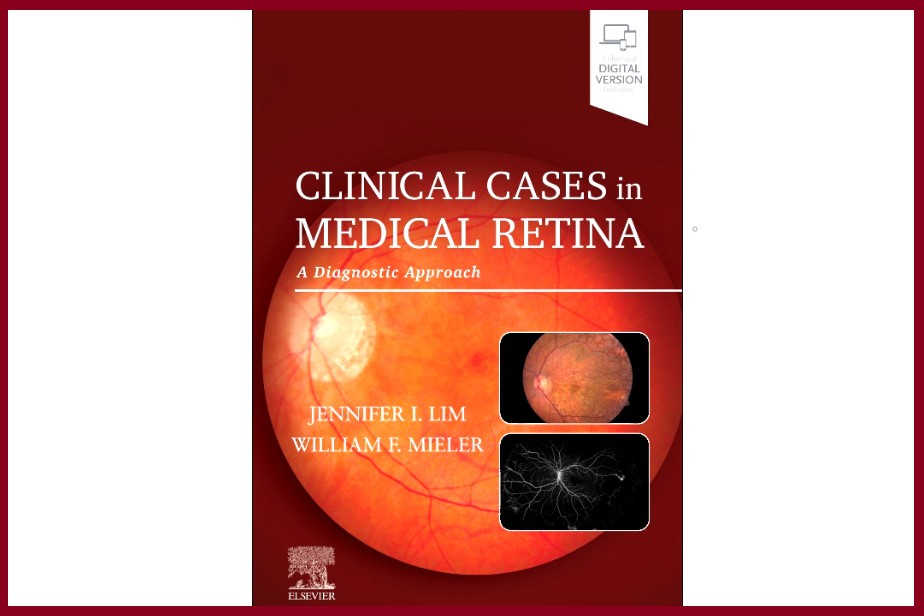

Armed with AMD progression risk data as well as the ability to classify AMD severity, the next logical step is to be familiar with the results of the Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS/AREDS2)5-6. These studies demonstrated those taking a particular group of supplements were able to reduce the risk of progression of intermediate AMD to late AMD by about 25% over the course of five years. Concern over the ingredient beta-carotene and the increased risk of lung cancer in smokers led to its replacement by similar carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin in subsequent AREDS2 testing. Now, with 10-year follow-up data, the latest findings reaffirm the benefits of the AREDS2 formula in reducing risk of AMD progression to late AMD as well as confirming the original 15mg daily dose of beta carotene conferred an almost doubling of lung cancer risk.

Table 2. AREDS2 supplement formula

Given the demonstrated benefits of AREDS2, any patient with a diagnosis of intermediate to late AMD should be provided the opportunity to discuss the benefits of AMD supplementation with their ocular health provider, which is certainly not limited to retinal clinicians. Before embarking on this, there are a few considerations which can aid the discussion. A trip to the local pharmacy reveals several supplementation brands are available off the shelf, but none have the exact AREDS2 formula concentrations.

The commonly recommended Blackmores Macu-Vision will give part of the AREDS2 formula only if specifically directed to take one tablet twice daily, rather than the label’s once-a-day recommendation. Completion of the formula is achieved by adding Blackmores Lutein Defence. This combination currently costs around $104 to $150 for a three-month supply from the cheapest pharmacies.

Clinicians-branded VisionCare with Lutein contains the complete AREDS2 formula, albeit with a lower daily zinc dose of 15mg. Notably, AREDS2 compared 25mg vs 80mg of daily zinc and did not find a statistical difference in benefit. This supplement will cost around $80 to $94 for a three-month supply, with an additional $15 for a three-month supply of 15mg daily zinc.

Several other brands are available, marketed under eye health supplements and all with varying combinations and concentrations ‘inspired’ by the AREDS formulation.

It appears that AREDS2 supplementation will cost patients around $100 for three months, which for some represents a significant financial burden. Where possible, encouragement of a varied diet with a range of coloured fruits and vegetables and regular fish intake is also likely to reduce the risk of development or progression of age-related macular degeneration.

Last but never the least, enquire about smoking status. Not only is this one of the biggest risk factors for AMD development and progression but many eye supplements also include small amounts of beta carotene.

The author has no conflict of interest to declare in the writing of this article

References

1. Socioeconomic cost of macular degeneration in New Zealand: Assessing the impact of visual impairment www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/socioeconomic-cost-macular-degeneration-in-nz.html#

2. Ferris, Frederick L 3rd et al. “Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration.” Ophthalmology vol. 120,4 (2013): 844-51.

3. Wykoff, Charles C et al. “Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in patients with diabetic macular oedema (YOSEMITE and RHINE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trials.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 399,10326 (2022): 741-755.

4. Ferris, Frederick L et al. “A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 18.” Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960) vol. 123,11 (2005): 1570-4.

5. National Eye Institute. AREDS/AREDS2 Clinical Trials. National Eye Institute (NEI) www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/age-related-eye-disease-studies-aredsareds2/about-areds-and-areds2 Accessed Feb 25, 2023.

6. Chew, Emily Y et al. “Long-term effects of vitamins C and E, β-carotene, and zinc on age-related macular degeneration: AREDS report no. 35.” Ophthalmology vol. 120,8 (2013): 1604-11.e4.

Dr Kevin Dunne is a consultant ophthalmologist specialising in medical retina and cataract surgery. He is based at Manukau SuperClinic and Eye Institute in Auckland.