Diabetes care by ethnicity at Greelane Clinical Centre

Māori patients are disproportionately affected by diabetes in New Zealand1. The prevalence of diabetes among Māori is twice that of Pakeha1, and Māori have higher rates of diabetic complications, including hospitalisation due to end-stage renal disease, lower-limb amputations, reduced time to first major cardiovascular event, and sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (DR)2-4.

Inequities in healthcare provision to Māori patients have also been documented across a range of specialty services5,6.

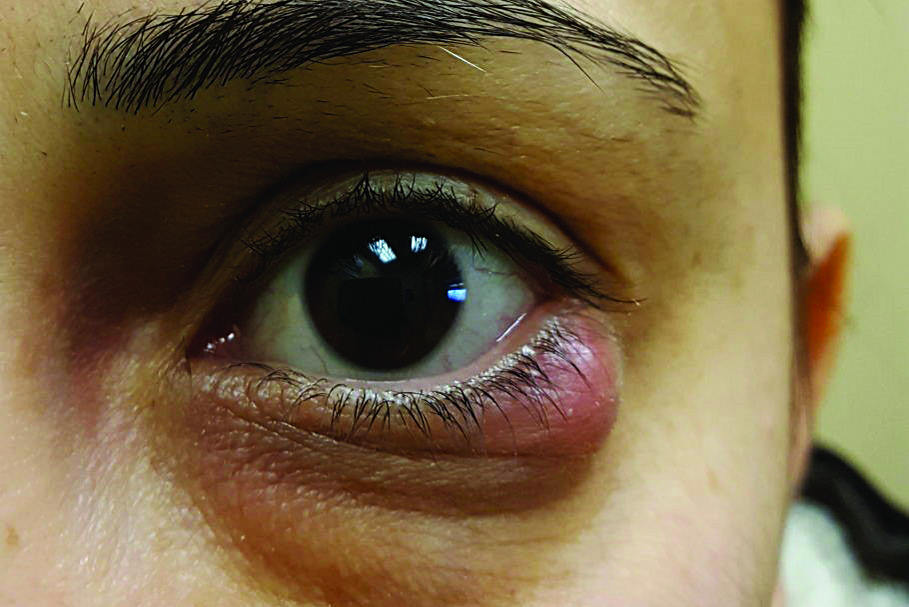

Although DR prevalence is increasing, and disproportionately affects Māori and Pasifika, the extent of inequity in the standards of DR care provided by ethnicity is largely unknown7-9. Our study aimed to evaluate the comprehensiveness of history taking, examination and treatment decisions in first specialist DR appointments by ethnicity at Greenlane Clinical Centre, Auckland.

Clinical records of all 388 patients seen in the DR clinic, referred between January 2021 to August 2022, were analysed. We found no difference in the quality of history taking, examination, investigations and treatment offered to patients by ethnicity. These are unique and promising findings – studies of general practice and cardiac revascularisation have found less time on history taking and fewer investigations and treatments offered to Māori patients, despite the same eligibility for treatment as Europeans5,6.

Fig 1. Māori patients had a significantly higher number of treatments they were eligible for at presentation (p=0.003)

Māori patients were under-represented in referrals to ophthalmology for their disease burden in the Auckland population and had a significantly higher number of treatments they were eligible for (see Fig 1). This represents more severe disease, delayed presentation and increased barriers to accessing DR screening and referral to tertiary care. Known barriers from previous literature include physical distance, cost, fewer GP referrals, poor diabetes education and previous experiences of culturally insensitive comments10-12. Marae-based diabetes education and cervical screening clinics in Auckland have improved participation in exercise and health screening among Māori13,14. Promoting such educational and DR screening clinics in marae may improve the uptake of screening and referral to ophthalmology.

Although referral numbers for Māori patients were low, the overall rates of attendance to initial and rescheduled ophthalmology appointments were comparable between Māori and other ethnicities in this study. Previous research has shown the non-attendance rate to ophthalmology specialist appointments among Māori is initially high but improves for follow-up appointments15. Common reasons for missing appointments include previous negative staff interactions and inability to contact clinic schedulers15. Our study highlights that, with significant effort by clinic schedulers and with culturally sensitive care, we are able to achieve equivalent eventual clinic attendance for Māori patients. Greenlane Clinical Centre staff must be commended for these efforts and this work should be continued.

The overall documentation of a complete assessment and treatment plan was suboptimal across all ethnicities. Common treatments missed were performing CPAC scores for significant cataract, referral to diabetic nurse clinic for an HbA1c of >100 mmol/mol, and commencing intravitreal Avastin (bevacizumab) for macula oedema with a visual acuity of 6/9 or worse. A proforma for DR consultations could improve quality of assessment and hence treatment for all patients.

References

1. Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand. Virtual Diabetes Register and web tool. 2021 [updated 2023 Mar 27; cited 2023 Apr 2]. https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/our-health-system/data-and-statistics/virtual-diabetes-tool

2. Ministry of Health. Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2015 (3rd Edition). [updated 2018 Aug 2; cited 2023 Apr 2]. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/tatau-kahukura-maori-health-statistics/nga-mana-hauora-tutohu-health-status-indicators/diabetes

3. Kenealy T, Elley CR, Robinson E, et al. An association between ethnicity and cardiovascular outcomes for people with Type 2 diabetes in New Zealand. Diabet Med. 2008 Nov;25(11):1302-8

4. Yu D, Zhao Z, Osuagwu UL, et al. Ethnic differences in mortality and hospital admission rates between Māori, Pacific, and European New Zealanders with type 2 diabetes between 1994 and 2018: a retrospective, population-based, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Feb;9(2):e209-217

5. Sandiford P, Bramley DM, El-Jack SS, Scott AG. Ethnic differences in coronary artery revascularisation in New Zealand: does the inverse care law still apply? Heart Lung Circ. 2015 Oct;24(10):969-74

6. Crengle S, Lay-Yee R, Davis P, Pearson J. A Comparison of Māori and Non-Māori Patient Visits to Doctors: The National Primary Medical Care Survey (NatMedCa). Wellington (NZ): Ministry of Health; 2005

7. Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012 Mar;35(3):556-64

8. Rogers JT, Black J, Harwood M, Wilkinson B, Gordon I, Ramke J. Vision impairment and differential access to eye health services in Aotearoa New Zealand: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 13;11(9):e048215

9. PwC New Zealand. The Economic and Social Cost of Type 2 Diabetes. 2021 Mar [cited 2023 Apr 3] https://healthierlives.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/Economic-and-Social-Cost-of-Type-2-Diabetes-FINAL-REPORT.pdf

10. Simmons D, Weblemoe T, Voyle J, et al. Personal barriers to diabetes care: lessons from a multi-ethnic community in New Zealand. Diabet Med. 1998 Nov;15(11):958-64

11. Harbers A, Davidson S, Eggleton K. Understanding barriers to diabetes eye screening in a large rural general practice: an audit of patients not reached by screening services. J Prim Health Care. 2022 Sep;14(3):273-79

12. Low J, Cunningham WJ, Niederer RL, Danesh-Meyer HV. Patient factors associated with appointment non-attendance at an ophthalmology department in Aotearoa New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2023 Apr 14;136(1573):77-87

13. Ormandy J, Phillips S, Campbell M, et al. ‘I was able to make a better decision about my health.’ Wāhine experiences of colposcopy at a marae-based health clinic: A qualitative study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2024 Feb 29. Epub ahead of print

14. Simmons D, Voyle JA. Reaching hard-to-reach, high-risk populations: piloting a health promotion and diabetes disease prevention programme on an urban marae in New Zealand. Health Promot Int. 2003 Mar;18(1):41-50

15. Low J, Cunningham WJ, Niederer RL, Danesh-Meyer HV. Patient factors associated with appointment non-attendance at an ophthalmology department in Aotearoa New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2023 Apr 14;136(1573):77-87

Jahnvee Solanki is a non-vocational ophthalmology registrar at Greenlane Clinical Centre. She completed her Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery at Auckland University in 2020 and a Postgraduate Diploma in Ophthalmic Basic Sciences with the University of Sydney in 2024.

Dr Rachael Niederer is a RANCZO ophthalmologist and researcher. She is a member of the RANZCO Māori and Pasifika Committee and has been involved in previous research exploring health disparities in eye health in New Zealand.

Dr Sarah Welch is a consultant ophthalmologist and the clinical director of the ophthalmology department at Greenlane Clinical Centre.