Dry eye and autologous serum?

The tear film and ocular surface are extremely complex, with tear film playing a vital role in maintaining ocular surface health. Not only does it provide lubrication but also many neuropeptides, vitamins and growth factors essential for the health of the corneal epithelium. Given the complexity of the tear film, it seems a small miracle that it functions normally in anyone.

Meanwhile dry eye disease (DED) is encountered on a daily basis by eye health professionals and accounts for a range of mild to severe discomfort symptoms (pain, burning sensations, eye fatigue, light sensitivity, redness etc.) made worse by virtually all types of ocular surgery. The worsening of this condition post-surgery is fortunately present for only a finite period for most people and will eventually return to its preoperative level. As ophthalmologists, we see this regularly after refractive laser procedures, but also after cataract and retinal surgery. Less commonly, surgery exacerbates severe ocular surface disease following chemical trauma, or associated with neurotrophic epithelial defects, or conjunctival cicatrising conditions like Stevens Johnston syndrome.

Traditionally when treating DED, we focus on optimising the lipid layer on the surface of the tear film to reduce the evaporation of tears and facilitate spreading of the tear film on the ocular surface; maintaining or supplementing the aqueous layer to normalise the osmolarity of the tear film; and treating any concurrent ocular inflammation, typically with steroids.

Although it is recognised that the neuropeptides and growth factors in the tear film are vital to the health of the ocular surface, supplementing these proteins has not, to date, been an integral component of DED treatment. This has, in part, been because the actions of these factors have not been well understood, but it has also been difficult to isolate and produce these proteins. With the increasing recognition of the prevalence and significant socioeconomic costs of this condition, however, there has been renewed interest in DED.

In the 1970s, doctors recognised that many of the proteins and growth factors present in the tear film were also present in serum.

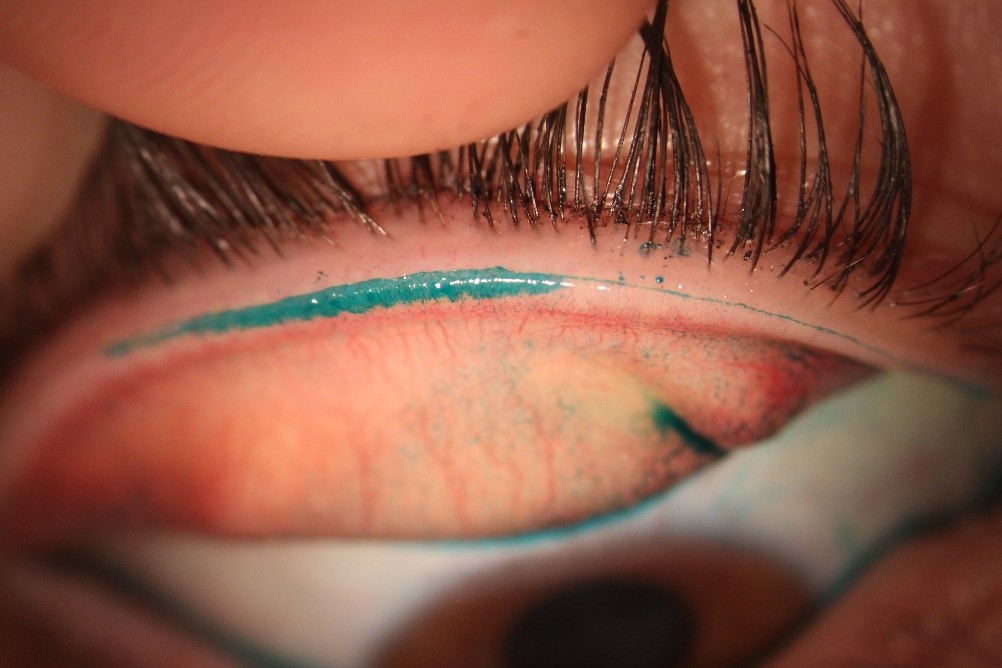

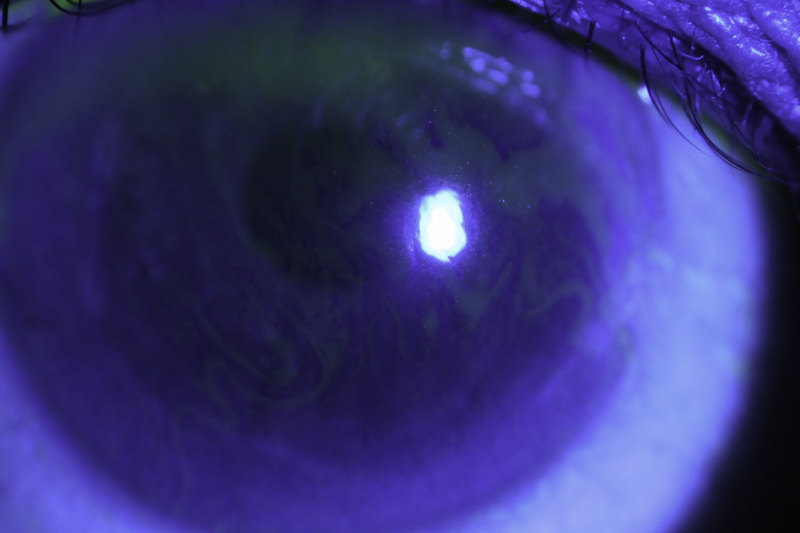

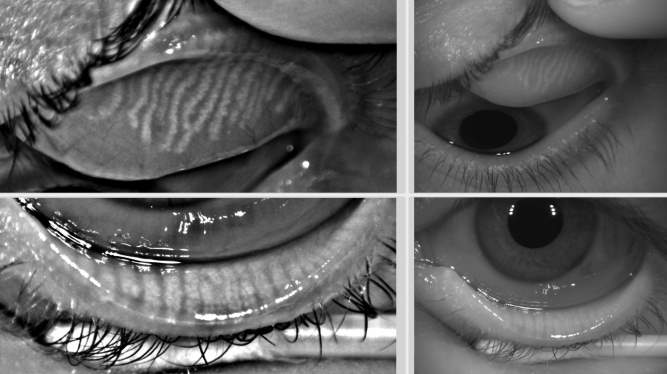

Autologous serum eye drops have been used with considerable success in patients with severe chemical burns. Then, in the 1980s, the application of serum eye drops was extended to the treatment of other forms of severe ocular surface disease and non-healing neurotrophic corneal ulcers, resulting in significant clinical evidence for the benefit of serum in these conditions (Fig 1 and Fig 2).

Fig 1. Neurotrophic ocular surface disease, due to presumed HSV, prior to treatment with SEDs

Fig 2. The same case showing dramatic improvement four weeks after commencing SEDs

In 1984, Fox et al published a paper showing autologous serum eye drops (SEDs) were helpful in treating severe DED, leading to increasing interest in this area. However, it is still not considered a mainstream therapy for this condition. This is partly because of the logistics of generating SEDs, but also because clinical trials have demonstrated variable benefits with respect to treating dry eye.

A recent Cochrane review, based on a limited number of randomised clinical trials, demonstrated that SEDs alleviate dry eye symptoms better than artificial eye drops for the first couple of weeks, but data still remains inconclusive regarding clinical efficacy over long-term periods.

SEDs are essentially prepared by taking a patient’s blood, allowing it to clot, then spinning it in a centrifuge to separate the red blood cells from serum. The serum is then removed and mixed in varying proportions with normal saline, before being separated into bottles, each with enough serum to provide up to a week’s treatment. These are then frozen and, at the beginning each week’s treatment, a single bottle is defrosted.

Preparing SEDs involves a considerable amount of resource and there is a small risk of contamination if not handled appropriately, so it’s important the patient is fully informed about the need for careful handling. There are also strict protocols regarding drop preparation. These may vary from one service to another, although my understanding is that this is standardised across the New Zealand blood service, where the drops are 25% serum and 75% saline. In other countries 50% or 100% serum mixtures may be used. Unfortunately, there isn’t consensus in the literature regarding the most effective serum concentration.

If a patient is unable to give blood due to concurrent medical conditions, it is also possible to prescribe allogenic serum eye drops. These are prepared in the same way as autologous serum eye drops, except the blood is sourced from another patient.

As medical professionals, we like our practices to be guided by sound scientific evidence regarding clinical efficacy. The clinical evidence for treating chemical ocular burns, severe ocular surface disease (Stevens Johnston Syndrome) and non-healing neurotrophic ulcers is relatively strong, however a similar level of evidence does not yet exist for DED. Despite this, SEDs are recognised by most ophthalmologists as an important option for some DED patients who have not responded to other treatments. It is generally accepted that not all, but many patients show clinical improvement on this treatment, when other traditional treatments fail.

The lack of evidence highlights the difficulties in running clinical trials on conditions that have, until recently with TFOS DEWS II, been relatively ill-defined, and where clinical signs often show very little relationship to the patient’s symptoms.

Serum drops remain an evolving therapeutic option. Some groups are now using other blood-derived products which may offer superior therapeutic benefits over standard SEDs. The first is Eye PRP which uses a process to create platelet enriched plasma with a reportedly higher concentration of growth factors. The second is ‘plasma rich in growth factors’ PRGF which uses a different process again to increase the concentration of growth factors. Preliminary trials involving both preparations have shown clinical benefits.

Finally, Moorfield’s Eye Hospital ran a small trial where patients were taught how to use a drop of whole blood from a pinprick on their finger, four times a day for eight weeks. Significant improvements were noted in several parameters, such as visual acuity, corneal staining, tear break-up time (TBUT) and ocular comfort index (OCI), but not the Schirmer’s test.

So, we can expect more exciting developments to come in this area.

References

Alio JL, Arnalich-Montiel F, Rodriguez AE. The role of “eye platelet rich plasma (E-PRP)” for wound healing in ophthalmology. Curr Pharm Biotechnol (2012)

Anitua E, de la Fuente M, Riestra A, Merayo-Lloves J, Muruzabal F, Orive G. Preservation of biological activity of plasma and platelet-derived eye drops after their different time and temperature conditions of storage. Cornea (2015)

Del Castillo JM, de la Casa JM, Sardina RC, et al. Treatment of recurrent corneal erosions using autologous serum. Cornea 2002;21:781–3.

Fox RI, Chan R, Michelson JB, et al. Beneficial effect of artificial tears made with autologous serum in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:459–61

Lopez-Plandolit S, Morales MC, Freire V, Grau AE, Duran JA. Efficacy of plasma rich in growth factors for the treatment of dry eye. Cornea (2011)

Pan Q, Angelina A, Marrone M, Stark WJ, Akpek EK. Autologous serum eye drops for dry eye. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2017)

Than J, Balal S, Wawrzynski J, Nesaratnam N, Saleh GM, Moore J, Sharma A et al. Fingerprick autologous blood: a novel treatment for dry eye syndrome. Eye (Lond) (2017)

Tsubota K , Goto E, Fujita H, et al. Treatment of dry eye by autologous serum application in Sjögren’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:390–5

Tsubota K , Satake Y, Ohyama M, et al. Surgical reconstruction of the ocular surface in advanced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome [see comments]. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;122:38–52.

Dr Nick Mantell specialises in cataract, laser vision correction and vitreoretinal surgery with the Eye Institute in Auckland and is a former clinical senior lecturer with the Department of Ophthalmology at Auckland University.