Dry eye: patient involvement is key

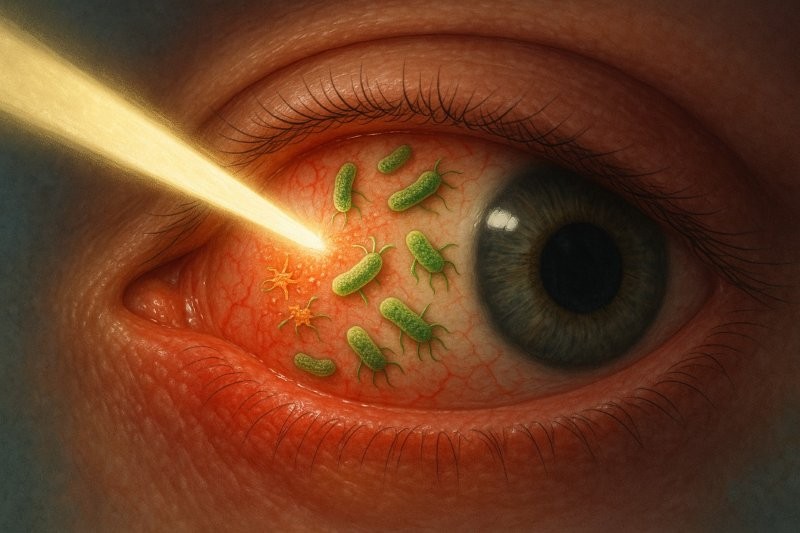

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common condition with prevalence rates reported to be as high as 50% and, as such, is one of the most frequently presenting conditions in clinical practice. Its chronic and multifactorial nature means that many patients face a long and complex journey to receiving an accurate diagnosis and effective management. In this context, greater patient and public involvement (PPI) is not only beneficial – it becomes essential.

Challenges in the current landscape

Globally, individuals living with DED can face considerable challenges in accessing effective care. Hospital appointments are often denied as the condition fails to meet the threshold for consultation but, even when granted, long waits and time-limited consultations can leave patients with DED feeling unheard and inadequately supported. This leaves patients often having to advocate for themselves, navigating the various healthcare pathways without sufficient guidance or empathy. A lack of continuity and fragmented services contribute to what can be described as ‘doctor-hopping’, where consistent care is replaced by disjointed, often expensive and frequently short-term interventions.\

Dry eye care has improved vastly in recent years and for New Zealanders is now among the most comprehensive in the world. Initiatives such as the global consensus Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop (TFOS DEWS II) reports have helped raise awareness about the disease and increased access to appropriate care for many; however, barriers remain. Affordability of assessment and treatment remains an issue in many countries where dry eye management is not subsidised, while communication is also reported as suboptimal by many of those affected. Across the world, patients with dry eye frequently report not feeling listened to during appointments, with insufficient time dedicated to understanding their symptoms or exploring appropriate management options. This lack of meaningful dialogue can exacerbate feelings of frustration, anxiety and helplessness.

From a clinical perspective, improving DED care requires both investment of time and money as well as continuing professional development to keep up with the latest evidence. This limits the number of centres – which are often concentrated in more urban areas – that are able to offer comprehensive diagnostics, treatment and follow-up. Limited access to modern diagnostic tools and advanced therapies perpetuates health inequities, particularly for those in regional or rural areas.

Empowering the patient voice

Patients are experts in their own condition so can play a valuable role in making real, constructive changes to service provision. Involving patients in a meaningful way can help ensure clinical practice is more responsive and tailored to actual needs.

Feedback tools such as review platforms, moderated forums and structured surveys provide valuable insights into the patient experience. These can help inform service development, clinical education and research priorities. Embedding PPI in everyday practice also benefits clinicians. It shifts care from transactional to relational, which serves to strengthen long-term trust. Engaged patients are much more likely to adhere to management plans, refer others and remain loyal, enhancing both health outcomes and professional fulfilment.

Education, awareness and the future

So what’s going on in New Zealand to try to address some of these issues? Well, we have the Dry Eye Association NZ (DEANZ) that was launched in April 2024, following the launch of the Dry Eye Association UK in late 2023. This offers support and recognises the value of public engagement in shaping dry eye care. The association’s mission is to improve the lives of those living with DED and related conditions by raising awareness and providing educational resources. Led by a collective of patients and eyecare professionals, the association seeks to serve as a central hub for accessible, evidence-based information, practical advice and advocacy.

With content guided by patient-identified knowledge gaps and patient-reported needs, the platform offers day-to-day management tips, explores emerging treatments, outlines opportunities for clinical trial participation and fosters a sense of community for those living with what can often be an isolating condition. While there’s no instant fix for DED, the association recognises and offers hope that with the right support, DED is often manageable and quality of life can be greatly improved.

Leading by example

On 18 May 2025, DEANZ’s second free public event was held to educate and connect those affected by dry eye. Hosted by the Ocular Surface Laboratory in partnership with Re:Vision and sponsored by Bausch + Lomb and BioRevive, the event reinforced the value of public-facing engagement in improving DED care. As well as hearing from leading experts and receiving updates on current ocular surface research, attendees were offered the opportunity to connect with others through their personal experiences and share frustrations and aspirations in a format that can contribute to shaping both care provision and future research directions. There will be more on this year’s event in July’s issue of NZ Optics.

Those who experience the effects of DED themselves and manage patients affected by the condition readily accept that it’s more than just a diagnosis – it’s a lived experience with far-reaching impacts. By embracing patient and public involvement across clinical care, education and research, we have the opportunity to create more empathetic, effective and equitable systems. For practitioners, this approach stands to not only improve patient outcomes, but to bring greater purpose and fulfilment to clinical practice.

Dr Ally Xue is a therapeutic optometrist and postdoctoral research fellow with the Ocular Surface Laboratory (OSL) at the University of Auckland.

Professor Jennifer Craig heads up the OSL in the University of Auckland’s Department of Ophthalmology and was chair of the TFOS Lifestyle Workshop and vice-chair of TFOS DEWS II.