Making the move to nurse-led CXL clinics

Reflecting similar strategies in the UK and Ireland, a nurse-led corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) service is being established in Northland to ease the burden on local ophthalmologists. Drew Jones reviews how this is being received.

A 2018 New Zealand Herald article highlighted the case of an 11-year-old who was referred for corneal crosslinking (CXL), a minimally invasive procedure that combines riboflavin (vitamin B2) eye drops and UV to combat keratoconus progression by strengthening the cornea. The patient’s case was buried in a backlog of overdue appointments that Counties Manukau District Health Board (CMDHB) later admitted to investigators, “became extremely difficult to manage.” After falling through administrative cracks for two years and nine months from referral, the CXL procedure then saved some of the sight in the young patient’s left eye, although it was too late for her right. Other more recent reports have also detailed poor patient outcomes from late referrals, but sources in Auckland (who didn’t wish to be named) say there are simply not enough ophthalmologists to keep up with demand for CXL, even if cases are referred early enough by optometrists.

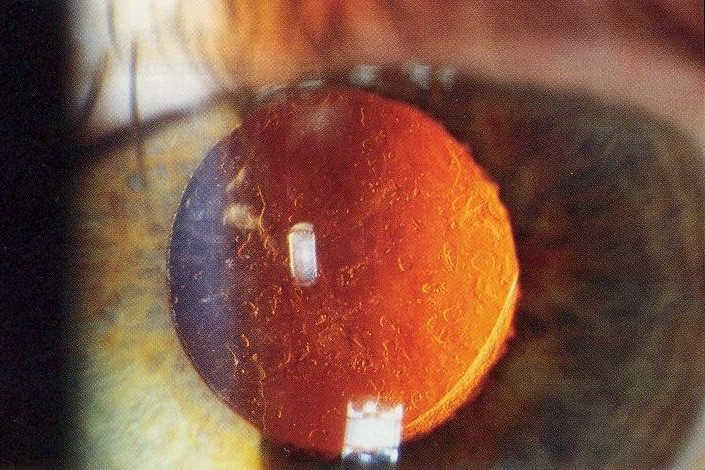

According to a 2012 study by Auckland University’s Professor Dipika Patel and Professor Charles McGhee, head of the Department of Ophthalmology, keratoconus had consistently been the leading indication for corneal transplantation in New Zealand for the past two decades, accounting for more than 40% of cases. “Indeed, New Zealand appears to have the highest reported proportion of transplantation surgery for keratoconus worldwide,” they found. The impact of corneal crosslinking, however, has been significant, wrote Prof McGhee and Dr Corina Chilibeck in August’s Eye on Ophthalmology*. “For decades, over 90% of all transplants performed in New Zealand were penetrating keratoplasties, and the majority were for keratoconus. Corneal crosslinking is a procedure that has been proven to halt or minimise the progression of keratoconus; in New Zealand, we estimate that more than 3,000 eyes with progressive keratoconus have now been treated with this procedure… (as) most large DHBs now provide this service… we are beginning to see the downstream effect on keratoconus-related corneal transplantation (Fig 1).”

Bridging the gap

“At Greenlane we have three nurse practitioners and eight nurse specialists, as well as a number of registered nurses who perform a variety of roles that have traditionally been performed by doctors,” said Auckland DHB’s ophthalmic clinical director Dr Sarah Welch. “The most striking example of this is that 90% of our Avastin (anti-VEGF) injections are now performed by nurses.”

Nurses are great for procedures such as laser** and anti-VEGF injections because they follow protocols so carefully they are probably more consistent than doctors, she said, adding that a nurse-led CXL clinic is simply another treatment procedure that will enable patients to receive more timely care. “We are not currently doing this in Auckland as we have another model, but I would support any centre that develops it. In general, most consultants have been very supportive of expanding the practice of our co-workers.”

Wellington-based ophthalmologist Dr Kenneth Chan said he and his colleagues are also happy for trained ophthalmic nurses to perform epithelium-on CXL, but doctors are still required for epithelium-off CXL (where the epithelial surface of the cornea is removed first) because of infection risk. Once this is done, a nurse can then administer the eyedrops and UV, he said. “I can certainly see the case for greater expansion in clinical scopes for ophthalmic nurses who are eager to upskill and perform some procedures that are currently performed by doctors.”

Anti-VEGF injections are now routinely given by nurses across the country, trained by colleagues in individual DHBs. But with the advent of Health NZ and the merging of DHBs, perhaps there’s now an opportunity to develop national training programmes to upskill ophthalmic nurses in a number of areas to help their ophthalmologist colleagues and improve patient waiting times, said Dr Chan.

CXL is relatively simple to perform, so there are few concerns about the actual procedure, said crosslinking specialist Dr Mo Ziaei. But it’s important that oversight and treatment recommendations are always provided by the specialist and there are peer-reviewed studies for both nurse-led and allied-health-led procedures before they become widely adopted, he said. In Auckland, Dr Ziaei has been involved in delivering a CXL service using both an optometrist and a junior doctor, with the service run virtually by a consultant, which may be a good model to consider, he said. “New Zealand has often lagged behind other countries like the UK, but given the demand for CXL and the current waiting times it is likely that CXL will be administered by allied health professionals here in the future.”

Dr Mo Ziaei

Northland ophthalmologist Dr Brian Kent-Smith agreed ophthalmologist oversight was paramount, however, stressing that the training of a nurse practitioner cannot be compared to that of a specialist. “The depth and quality of training is a tiny fraction of that required to be a specialist.”

Dr Brian Kent-Smith

The picture overseas

At Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, nurse-led CXL has been in place since 2014. It is led by Melanie Mason, Moorfields’ lead clinical nurse specialist for the Cornea & External Disease Service, who was the first nurse to perform the full procedure in the UK. Today Moorfields’ nurse-led CXL clinic screens patients, takes informed consent and manages the whole procedure, from mechanically debriding the epithelium to follow-up one week postoperatively. Results showing that Moorfields’ nurse-led CXL was as safe as that performed by ophthalmologists was partly the reason Mason earned the 2016 Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) Vision Pioneer award. There is always a corneal fellow or consultant available for a second opinion, said Mason, but it’s been the feedback from patients that has been especially encouraging. “I particularly appreciate being able to talk to patients about their condition, in a less time-pressured environment than the eye clinic.”

Moorfields' crosslinking nurse Melanie Mason

In Ireland, where CXL isn’t covered by most health insurers, September 2018’s World of Irish Nursing & Midwifery published a review showing that nurse-led CXL costs less than 5% of the same procedure performed by a consultant. It also slashed the mean waiting time for the procedure from 125 to 53 days and reduced the duration of patients’ hospital stays by more than 50%.

Diana Malata developed a nurse-led CXL service at the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital (RVEEH) in Dublin in January 2016. “I was very lucky because I was well supported by the corneal consultants when I presented the nurse-led CXL proposal to them. We adapted the Moorfields Eye Hospital CXL policy, agreed on the training programme and the corneal consultants were very involved in my surgical training,” she said, adding that she’d also seen and assisted in many procedures as a theatre nurse for more than 15 years including, more recently, corneal crosslinking. “I then worked as a clinical research nurse and a corneal nurse specialist for four years, where I was involved in a major European study about corneal transplants and worked in the cornea clinic.”

Understanding the concerns out there about the move to nurse-led CXL clinics led Malata to undertake an audit of her clinic’s work in 2017, which involved a medical student contacting many of her patients to enquire about complications and how they felt about a nurse doing the procedure. The results were overwhelmingly positive, she said, prompting a flurry of referrals from private consultants. “The corneal consultants here acknowledge the importance of early diagnosis and treatment to preserve the vision of keratoconus patients and prevent its progression to a stage where more invasive procedures such as corneal transplant are required. If patients can’t afford to pay for CXL privately, consultants refer them to me.”

Ireland's Diana Malata

Whether a doctor or a nurse performs CXL there is always a risk of corneal haze, sterile inflammation, keratitis and corneal scarring, said Malata. “I have performed more than 700 corneal crosslinking procedures since 2016. I see patients afterwards and during their keratoconus review, so I know some had corneal haze that gradually resolved after a month or two, plus one serious case of keratitis in 2018. I was well supported by the corneal consultants during the keratitis incident; I even performed the CXL for the patient's other eye, which went really well.”

Malata said, in her opinion, nurse-led services are the way forward in terms of improving patient care and reducing patient waiting times. “I would like to see more ophthalmic nurses doing CXL, superficial keratectomy, intravitreal injections, YAG laser and cyst excision. The main goal of service expansion is to achieve the best possible outcome for our patients. I hope that nurse-led CXL will be supported by New Zealand ophthalmologists as I have been supported here in Ireland.”

* https://eyeonoptics.co.nz/articles/archive/long-term-trends-in-keratoplasty-in-aotearoa/

**http://www.eyeonoptics.co.nz/articles/archive/you-too-can-laser/