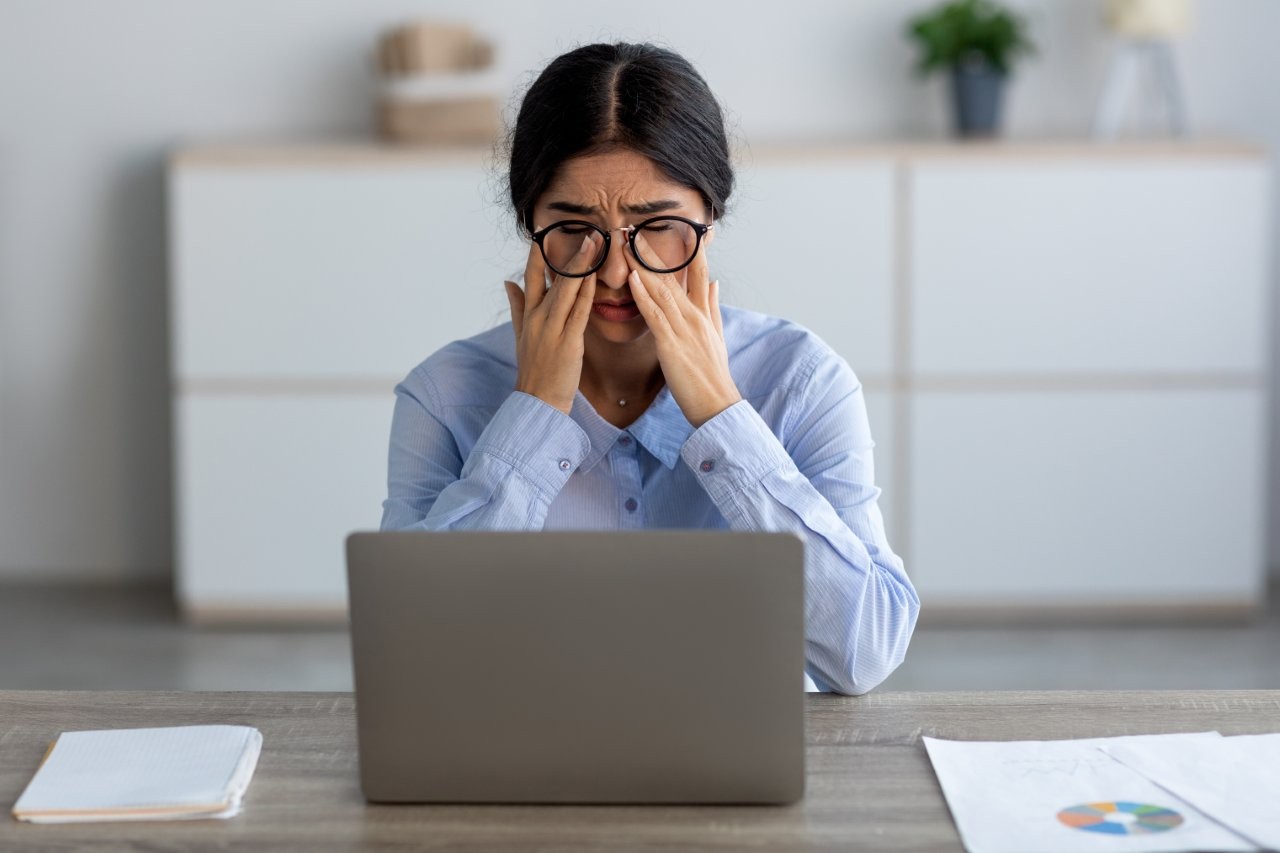

Our kid’s screen use is no dry issue

Of all the things we’ve had enough of lately, screen time is surely one. We might be navigating endless spreadsheets, overlapping Zoom meetings, frustrating home schooling, or helplessly doom-scrolling at midnight, but we’re also extremely fortunate to be able to learn and connect online.

Even before the pandemic, however, it was evident screens were here to stay. But do our eyes need a break?

In 2019, a few months before New Zealand’s first Covid-19 lockdown, over 450 young Aucklanders attending a gaming convention reported upwards of 43 hours of total weekly screen time. Today’s screen use likely makes those numbers pale in comparison. But gamers at that time acted as a proxy for high screen use among youth. This study, conducted by the team at the Ocular Surface Laboratory at the University of Auckland and recently published in Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, showed that extended (excessive) screen time was associated with clinical signs and symptoms of dry eye disease¹. Participants’ average age was 24, but many were teenagers – so not your typical dry eye candidate!

Humans are visual creatures

It’s tempting to blame gaming, but in this study gaming time alone did not correlate with any clinical measure. Total screen time did. Not “normal” screen use, but extended and consistent screen use, likely starting from a young age. This is a crucial distinction to older generations, as is understanding the pathophysiology and progression of dry eye disease over a lifetime. If you’re reading this, you probably grew up in a time where you had to beg parents for a screen, or share it with siblings, so you could have your turn at playing “Snake”. Needless to say, today is different. Cribs now come with tablet holders, schools are quick to usher in screen-based learning, and leisure and social activities are now significantly held online. Yet surprisingly little is known about the long-term implications of a habit we’ve adopted so fully. We’re coping, and we assume the same for our youngest.

As any parent of a toddler can attest, moving, colourful lights will draw (and keep) one’s attention for a long time, even more so if they’re interactive. Turns out, to swipe, tap and scroll is uncannily human, whether young or old. How else would we explain the universal compulsion to wake any screen in our peripheral perception from going into standby the moment it goes dark? Arguably, nothing in the history of humanity has so profoundly captivated our collective attention, filling our waking and sometimes even our sleeping hours to the brim.

The importance of blinking

The problem, however, is that when we’re focused on any static, cognitively demanding activity, whether on or off screen, we blink less. Studies have shown our blink frequency reduces by up to 90% when we’re looking at screens, a problem compounded by incomplete eyelid closure during blinking, which further exposes our ocular surfaces to the elements, leading to increased evaporation of the tear film². Once dry eye sets in, the unstable tear film leads to more blinking. This compensatory phenomenon was seen in our study’s young gamers, whose blink rates increased as they reported longer screen hours.

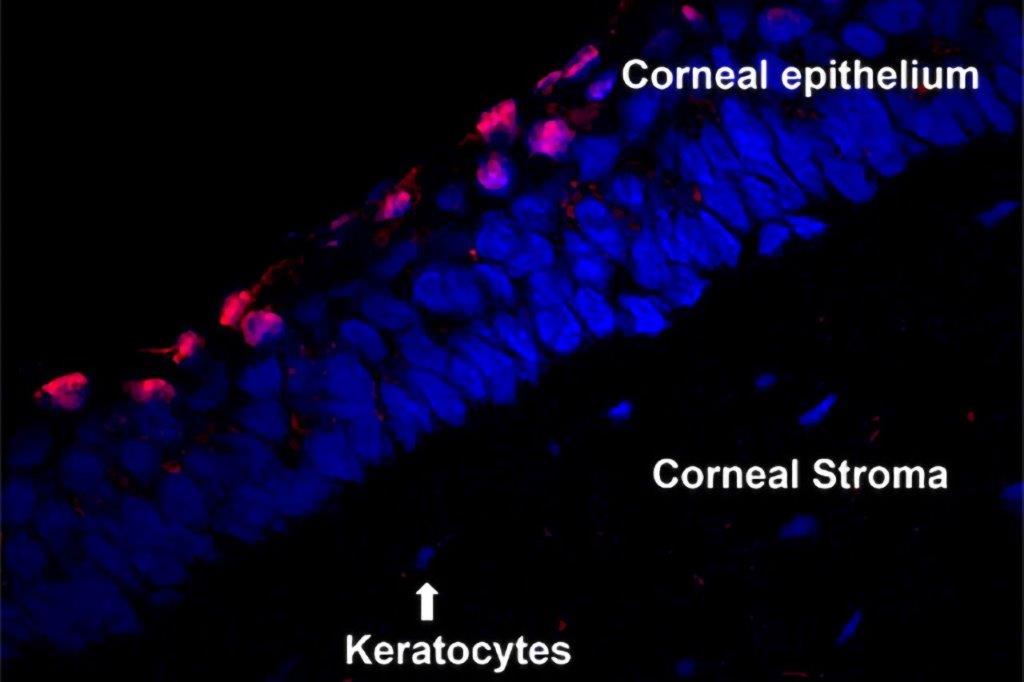

The hypothesis behind dry eye as a consequence of high screen use is that reduced blinking interferes with normal meibomian gland physiology, altering the quantity and quality of meibum and its distribution over the ocular surface. Underused glands, stagnant meibum, elevated intraglandular pressure lead to atrophy – irreversible gland dropout³. Clinically, we observe suboptimal tear film parameters and symptoms ensue, which is understandable, (physio)logically reasonable even, but is it concerning?

Untangling the effects of screen use

Excessive electronic screen use has been shown to be associated with severe meibomian gland atrophy in youth⁴, while another study, also emerging from the pandemic, has demonstrated a significant myopic shift in paediatric populations following just a few months of home confinement⁵. These are accessible markers for studying the effects of screen use because the tools required are relatively simple and non-invasive. But identifying and managing dry eye can also be elusive because of its multifactorial nature and the ocular surface’s functional reserves.

Untangling the effects of screen use is difficult. There are too many types of screens, kinds of users, sorts of apps and numbers of variables to accurately track and effectively control for. The picture is blurry, in no small part because there are unquestionable benefits to digital platforms as the pandemic has clearly shown. But emerging evidence is suggesting that excessive use is no good⁶.

Definitively proving the purported meibomian gland changes in response to reduced blinking from screen use and resultant dry eye and subsequent decrease in quality of life, requires longitudinal data over decades - an undertaking with astronomical implications on funding and logistics. Research will not fail to produce answers to these questions, it will just take time. Meanwhile we’re left with our daily habits, many of which amount to recognised modifiable risk factors for dry eye, which are currently being tackled in the ongoing Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Workshop ‘A Lifestyle Epidemic: Ocular Surface Disease’.

How much is too much screen time is a question most people, particularly parents, are currently grappling with. Evidence-based guidance will be paramount, but it seems that it’s the chronic use of screens that challenges our eyes’ functional reserves to restore and preserve ocular surface homeostasis day in, day out. Whether screens are to eyes what sugar is to teeth, only time and research will tell.

References

1. Muntz A, Turnbull PRK, Kim AD, Gokul A, Wong D, Tsay TS-W, et al. Extended screen time and dry eye in youth. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2021:101541

2. Wang MTM, Tien L, Han A, Lee JM, Kim D, Markoulli M, et al. Impact of blinking on ocular surface and tear film parameters. Ocul Surf 2018;16:424–9

3. Wang MTM, Craig JP. Natural history of dry eye disease: Perspectives from inter-ethnic comparison studies. Ocul Surf 2019:1–10

4. Cremers SL, Khan ARG, Ahn J, Cremers L, Weber J, Kossler AL, et al. New Indicator of Children’s Excessive Electronic Screen Use and Factors in Meibomian Gland Atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 2021

5. Wang J, Li Y, Musch DC, Wei N, Qi X, Ding G, et al. Progression of Myopia in School-Aged Children after COVID-19 Home Confinement. JAMA Ophthalmol 2021;139:293–300

6. LeBlanc A, Gunnell K, Prince S, Saunders T, Barnes J, Chaput J-P. The Ubiquity of the Screen: An Overview of the Risks and Benefits of Screen Time in Our Modern World. Transl J Am Coll Sport Med 2017;2:104–13

Dr Alex Müntz is a post-doctoral research fellow with a background in optometry, working in the Ocular Surface Laboratory at the University of Auckland.