Remembering Tony Morris

Well-known ophthalmologist and New Zealand refractive surgery pioneer Dr Tony Morris was remembered by family, friends and colleagues at a memorial service in Auckland in October.

Tony was one of the first ophthalmologists in New Zealand to perform radial keratotomy in 1985 and, in 1992, together with colleagues and later Eye Institute business partners Associate Professor Bruce Hadden and Dr Peter Ring, imported New Zealand’s first excimer laser.

But Tony wasn’t just a pioneering ophthalmologist, he was both entrepreneurial and visionary, said colleagues; “a financial whizz”, recalled Eye Institute’s former long-serving practice manager Barbara Hare in an earlier interview.

An optometry-ophthalmology champion

Contact lens pioneer, optometrist Paul Rose said Dr Morris was also one of the earliest ophthalmologists to understand the importance of building positive relationships with optometrists to better serve patients. He was one of a small number of ophthalmologist members to join the New Zealand Society of Contact Lens Practitioners (now the Cornea & Contact Lens Society of NZ) where he served as a councillor and president with Rose. “He held optometry in high regard. Tony even fitted contact lenses for a short period before recognising that this task fitted much better into an optometrist’s role.”

Former Eye Institute ophthalmologist, now principal of Re:Vision Dr Trevor Gray agreed, saying Tony was “significantly responsible” for developing a healthy, professional respect between ophthalmology and optometry in New Zealand. “This was thanks to Tony’s leadership and his dedication to professional education of optometrists in the era when RANZCO banned its members from lecturing to optometrists in Australia and New Zealand!”

An ophthalmology pioneer

Tony had the ability to predict where ophthalmology was heading and wasn’t afraid to bring these ideas and their associated technologies back to his practice in New Zealand, said Rose.

When it came to ophthalmology, Tony was a bit of a maverick with gifted hands, recalled Dr Gray. “Tony had an uncanny ability to identify new treatments and surgeries that were to become universally accepted years later, which early on led to some unfair criticism from those less skilled and less insightful. But Tony had the natural surgical skills and dogged determination to keep pushing the early forms of refractive surgery to ever-increasing levels of safety and quality of vision correction for his many thousands of appreciative patients.”

Dr Gray said he still sees some of Tony’s past patients whose lives had been transformed for the better and were still grateful to him years later.

Life outside ophthalmology

Tony could sometimes come across as arrogant and aloof, but this was due more to shyness than anything else, said Rose. “Though he didn’t rate idle conversation as a top priority!”

Auckland optometrist and researcher Grant Watters also recalled Tony’s somewhat taciturn nature, except when it came to talking about sailing, he laughed.

“Whatever Tony chose to do, he did with passion, even owning a catering venue and a boat building business for several years,” said Rose. “He had a love of the sea and was a competent diver. Golf was also a passion for him and although he confessed he never mastered the sport, he always invested in the latest technology and played regularly until his final day.”

Obituary: Dr Antony (Tony) Morris

By Dr Peter Ring

Dr Tony Morris died unexpectedly on 12 September. He had had health issues for some time, but his sudden death was not anticipated and was a great shock to his family and friends, including myself and our long-term colleague Associate Professor Bruce Hadden. We had both known Tony for a great many years having founded Eye Institute together in 1995.

Tony and his identical twin John, an orthopaedic surgeon living in Queensland, were born in Auckland and educated at St Kentigern College where they excelled scholastically. Both went on to the University of Otago Medical School and graduated in 1966. After two years as a house surgeon and eye registrar, Tony trained in ophthalmic surgery at the famous Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, finishing just as I was starting.

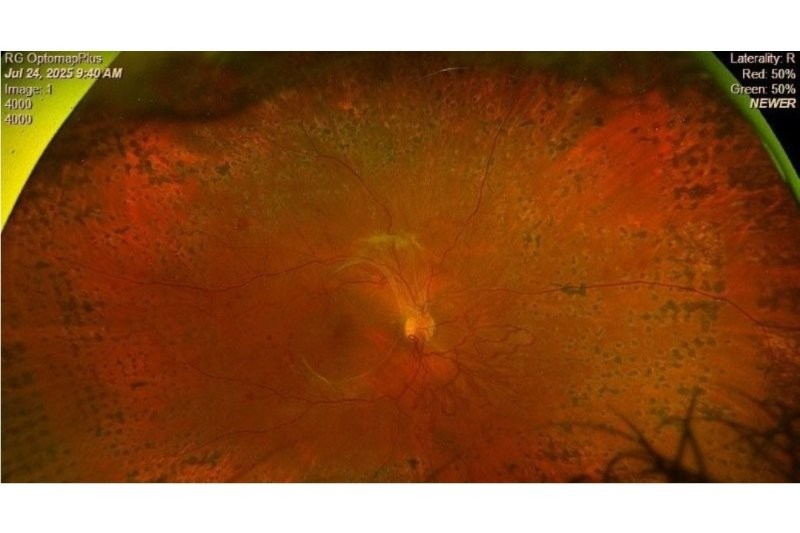

He returned to Auckland where he initially joined Drs Harold Coop and Lindo Ferguson on Remuera Rd. In the 1980s, he built a dedicated ophthalmic suite at 134 Remuera Rd and it was during this time that he became interested in refractive corneal surgery - an extension of his interest in contact lenses. I had similar intentions and we both carried out New Zealand’s first radial keratotomy procedures in the same week in 1986.

In 1990, Tony, myself and Bruce together decided it was time to embark on phacoemulsification for cataracts which by then was becoming the preferred technique in the US. Together we persuaded the Mater Misericordiae (now Mercy) Hospital, where we all operated, to purchase the equipment. That was our first learning curve together.

Excimer laser refractive surgery, initially photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), was developing overseas so Tony and I went to a meeting in San Diego in 1992 to view the machine and technique. We were persuaded and ordered a Summit laser on the spot. Returning home, we invited Bruce to join us as this was unchartered waters in the ophthalmic community, generating much opprobrium. We featured on the radio and in the press, where someone forecast many patients going blind in the future!

The three of us were still practising as individuals at this stage. Over the road from Tony’s practice an old bungalow came on the market at 125 Remuera Rd. Tony’s business skills came to the fore as we were to see so frequently in the future. His inspiration was for the three of us to join practices, buy the building and build New Zealand’s first dedicated ophthalmic day-stay surgical centre. This duly occurred and the building was formally opened by Governor-General Dame Cath Tizard on 24 February 1995. The Remuera Eye Clinic Day Surgery and Laser Centre was born; later to be renamed Eye Institute.

Initially we employed 19 staff. At the time, this seemed a huge undertaking for the three of us. But Tony’s vision for the future surpassed our own, with all three of us contributing different aspects that gelled into a partnership which worked harmoniously for the next 20 years. By then, the partnership had expanded to include seven ophthalmologists and space was a premium, so Eye Institute moved into another purpose-built building at 123 Remuera Rd. It was then, that Tony felt it was time to retire to make room for more younger ophthalmologists.

Tony’s interests outside ophthalmology were wide-ranging. He raced several yachts, including Diamond Knife, and owned a big-game fishing launch called Outer Limits. He even had a boat building business at one stage and he enjoyed scuba diving.

In the early days of Eye Institute, we had a number of fun Christmas parties on Tony’s boats. Second only to his marine interests, golfing became a passion. He enjoyed playing with his wife Margaret and they bought a place at Millbrook, near Queenstown. He was a member of the nearby exclusive Hills Golf course and generously allowed us to celebrate his retirement there. Tony also invested in several successful business and property ventures.

Tony was a man of few words which his patients accepted, and he had a big surgical practice. He was well-read and could discuss in-depth a wide range of topics outside his main sphere of interests. He was also generous to his staff, taking them to numerous conferences.

Tony’s enduring contributions to New Zealand ophthalmology were taking the lead in cataract surgery techniques, refractive surgery and ambulatory ophthalmic surgery, and he helped advance ophthalmology’s professional relationship with optometrists. In medicine, he served a term as president of the Auckland Division of the New Zealand Medical Association.

One little known aspect of Tony’s life was that he was a huge philanthropist. He established a cancer treatment in New Zealand called peptide radionuclide receptor therapy or PRRT, which is used to treat neuroendocrine tumours, and he funded an endowed chair, the Antony and Margaret Morris Chair in Translational Cancer Research. Both these huge legacies to the University of Auckland will be of enduring benefit to cancer treatment in our country.

To his two original partners, he was a very good friend and colleague. Without Tony’s enterprise we would not have had such interesting and successful careers and there would not have been an Eye Institute as we know it.

Tony leaves behind Margaret, his devoted wife of 55 years, their daughter Michelle and son Stephen, and four grandchildren, to whom I extend our sincere condolences.