Research enables safer test for blindness in preterm babies

University of Otago researchers have successfully developed and tested a safer way to administer pupil-dilating eye drops to preterm babies, informing new guidelines in New Zealand and around the world.

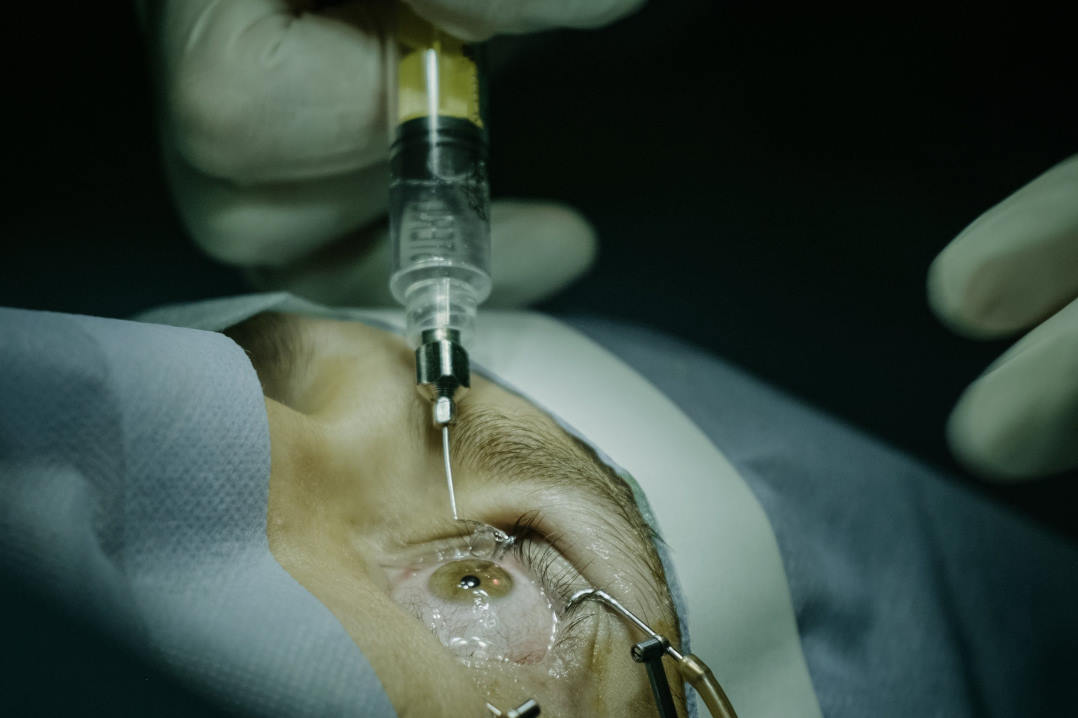

Every year in New Zealand and Australia roughly 540 very preterm babies (before 31 weeks) are born at risk of permanent blindness. They are offered an eye test, and if detected early, blindness and vision impairment can be prevented. However, adult doses and formulations of eye drops have traditionally been used for babies, which in some cases can result in serious adverse events affecting the heart, lungs and gastrointestinal system. In 2018, Cure Kids awarded a grant to a University of Otago team, led by Associate Professor David Reith, to investigate whether infants could be given a smaller dose of up to three microdrops (~7μL) in each eye of either a very low dose (0.5% phenylephrine and 0.1% cyclopentolate), or a low dose (1% phenylephrine and 0.2% cyclopentolate) mydriatic solution. The three-year safety and efficacy study, which was also supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand, included 150 preterm babies born in New Zealand between 2019 and 2021 and proved these smaller doses reduced side effects.

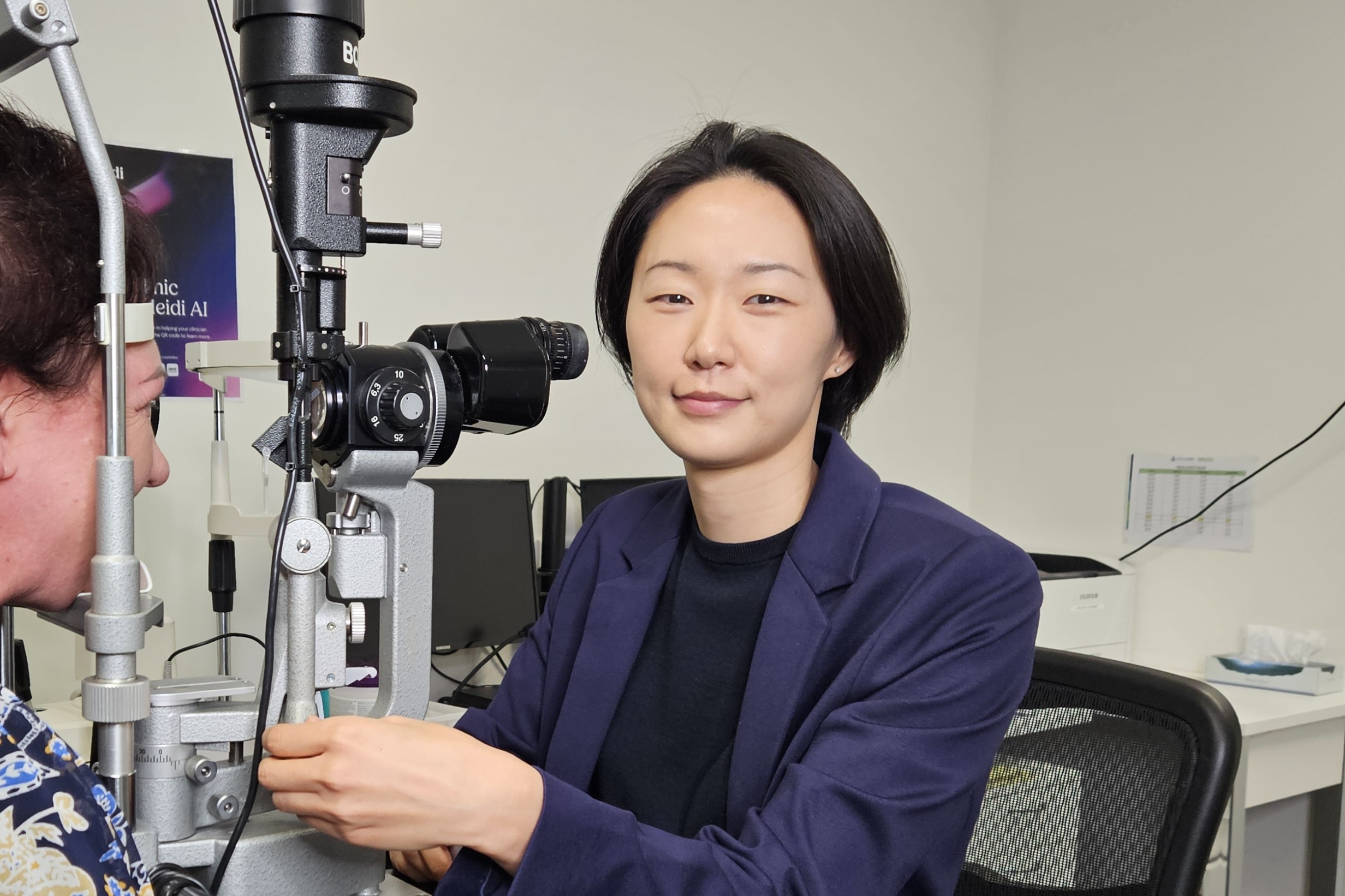

“We’re thrilled that the study will positively impact many families by reducing medicine-related harm,” said Lisa Kremer, a researcher at the School of Pharmacy, who specialises in safe and effective use of medicines in neonates. “This medical research breakthrough enables extra safety for critical eye screening in vulnerable preterm babies.”

Study’s focus on Māori babies

The study also investigated the effect of the lower dose drops on Māori babies, said Kremer. “This question has not previously been answered because there have never been any Māori participants in any published eye-drop studies.” The study had a high recruitment rate of Māori infants (20%) and results suggest safety and efficacy for this group was not significantly different from New Zealand European infants, she said.

Having already communicated the results of the study with the major hospitals caring for preterm babies around Aotearoa, the research team said it is hopeful the analysis and outcomes from ‘The Little Eye Drop Study’ will result in changes to best practice to benefit the millions of preterm babies around the world.