Thrombotic microangiopathy with Purtscher’s-like retinopathy findings

A 24-year-old male presented with bilateral patchy scotoma in both eyes and mild distortion on the left.

He had a significant history of recent and prolonged hospital admission for thrombotic microangiopathy. This is a clinical syndrome where there is haemolytic anaemia (destruction of red blood cells), thrombocytopaenia (low platelets), and organ damage due to the formation of microscopic blood clots in capillaries and small arteries. It is life threatening and can be caused by a multitude of entities. During his hospital admission, he demonstrated abnormal clotting and his platelets reached as low as 21,000/μL (normal range, 150,000-450,000/μL), indicating severe thrombocytopaenia. He was treated with plasma exchange and high-dose intravenous steroids.

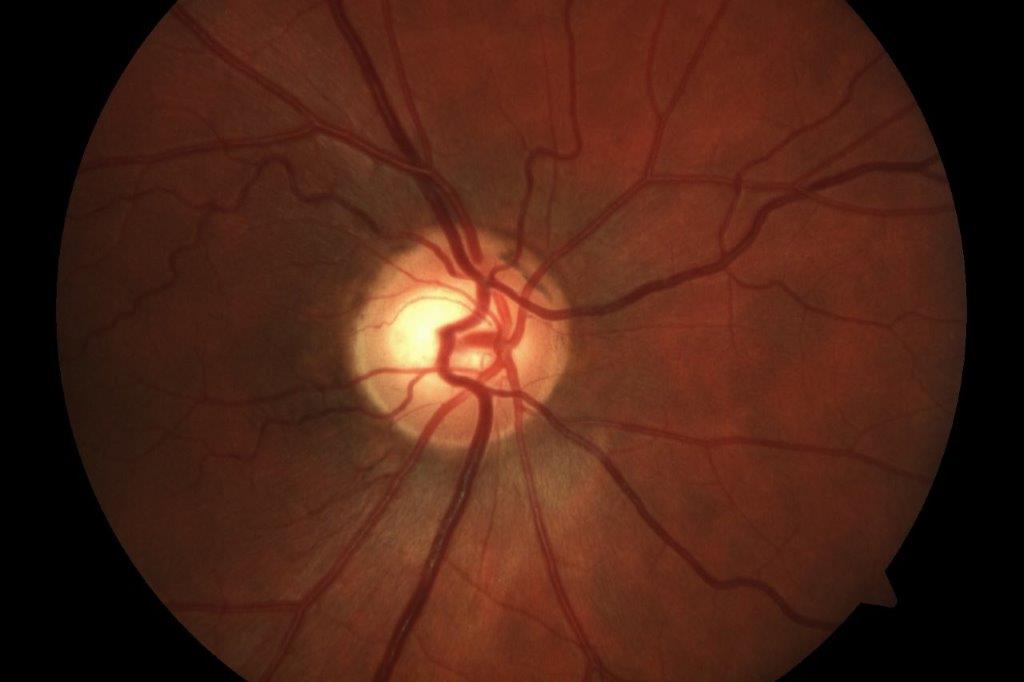

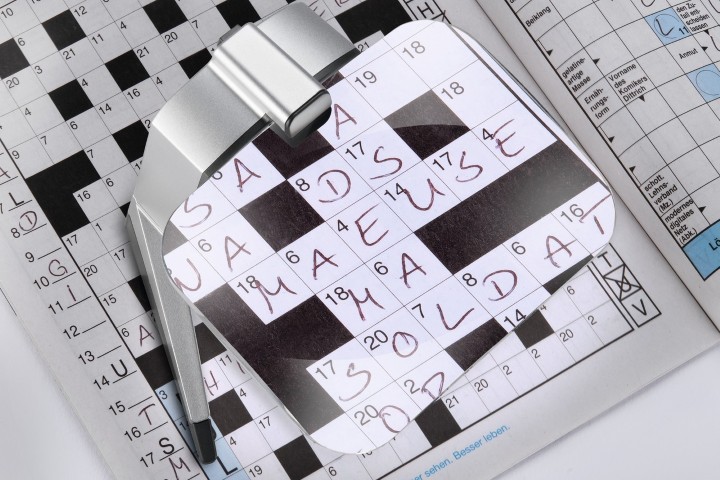

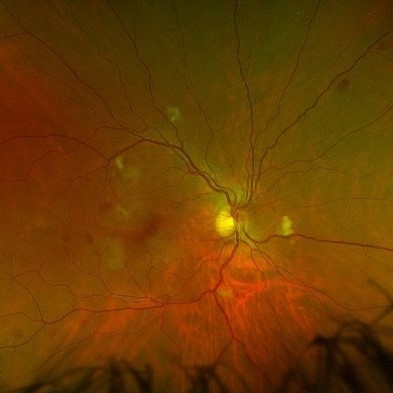

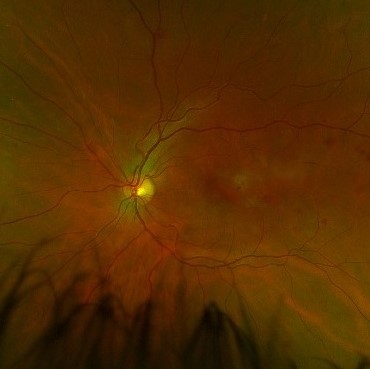

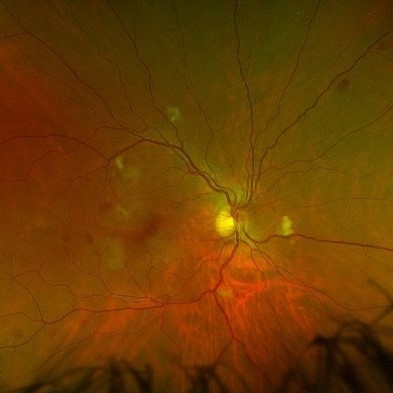

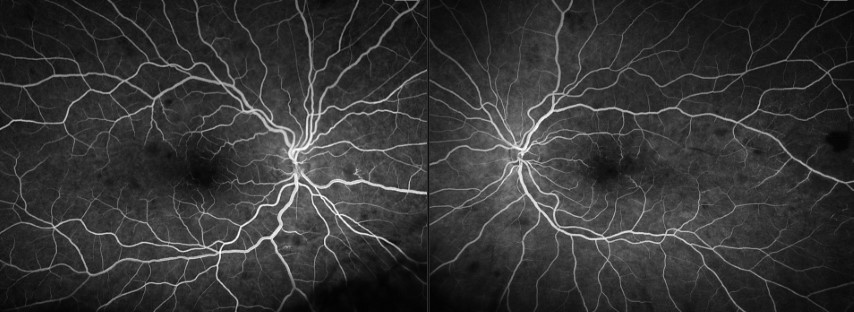

Figs 1a and 1b. Fundus examination revealed cotton-wool spots confined largely to the posterior pole and scattered deep peripheral retinal haemorrhages

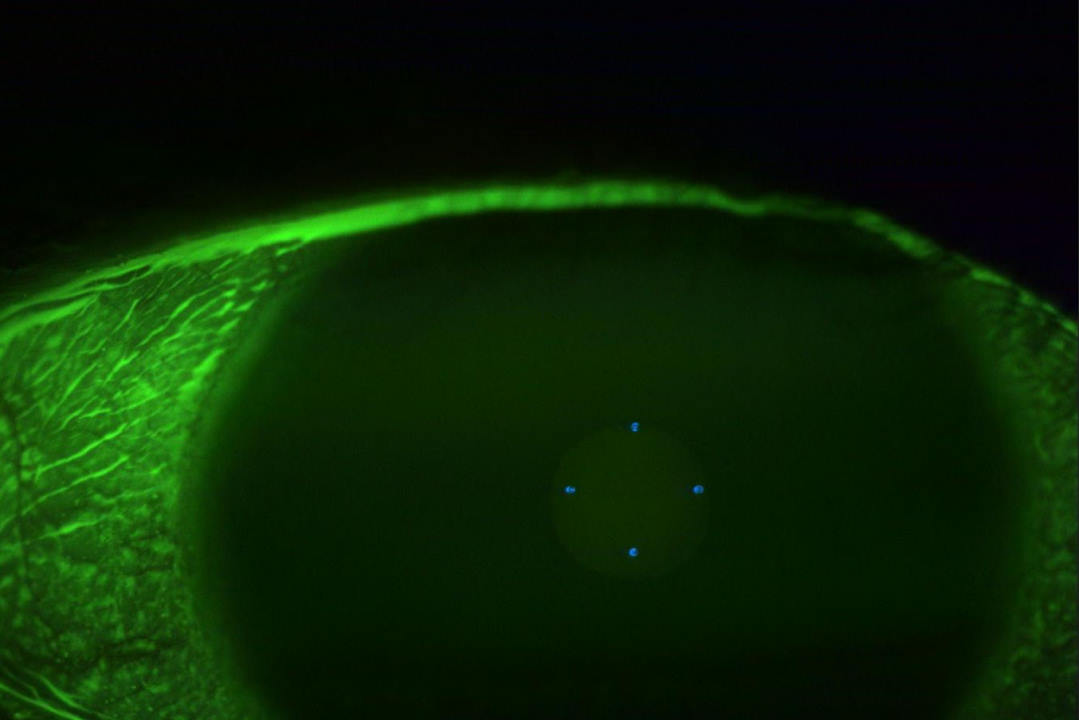

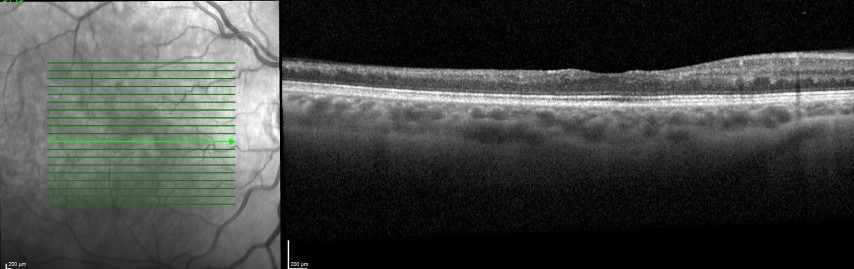

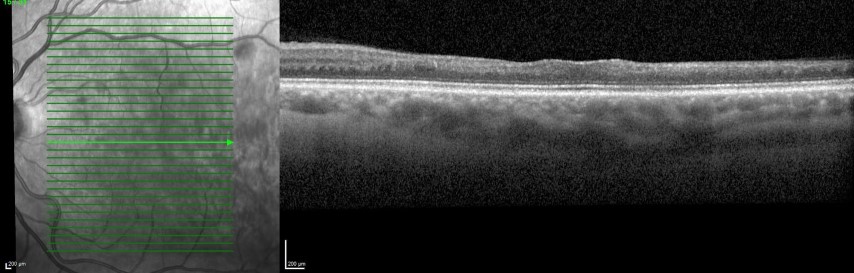

Upon stabilising his medical concerns, his visual symptoms were noted and he was referred for assessment. On examination, visual acuity was right 6/7.5, left 6/12, pinholing to 6/9.5. There was no pupil abnormality and Ishihara colour plates were full in both eyes. The anterior segment examination was completely normal bilaterally, as were the intraocular pressures. Fundus examination revealed cotton-wool spots confined largely to the posterior pole and scattered deep peripheral retinal haemorrhages (Fig 1a and 1b). OCT showed loss of the inner retina. On the right it was mainly temporal to fixation, but on the left it was more extensive (Fig 2a and 2b).

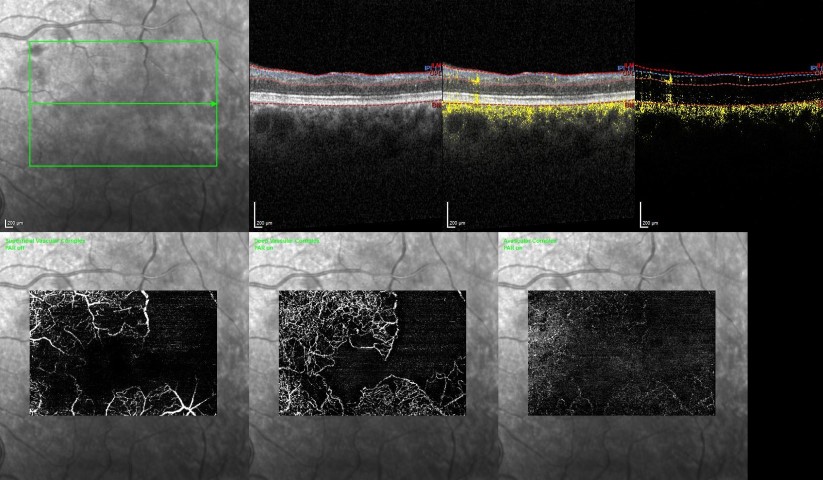

Fig 2a. Right eye OCT scan showing loss of inner retina, mainly temporal to fixation

Fig 2b. Left eye OCT scan showing extensive loss of inner retina

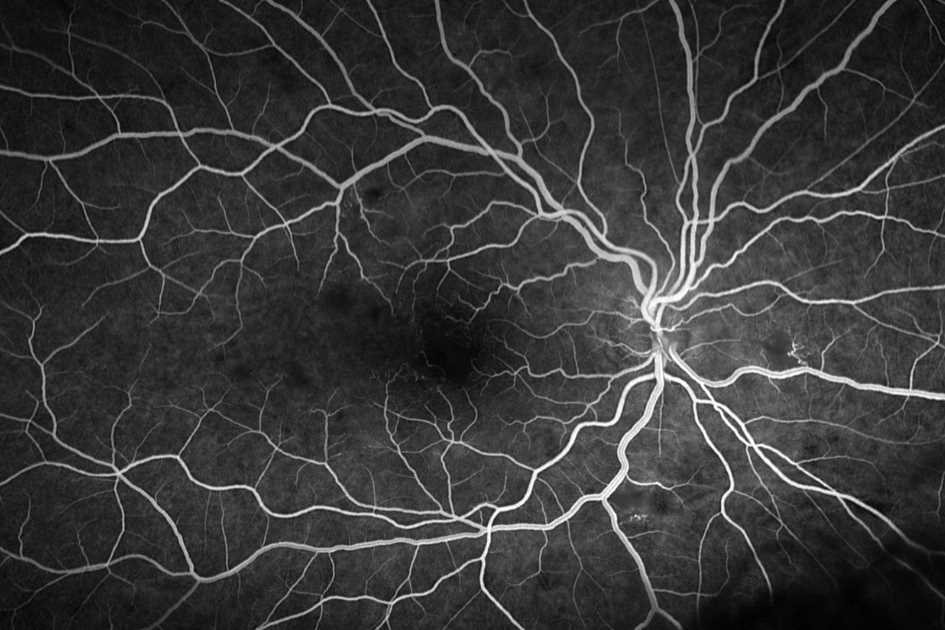

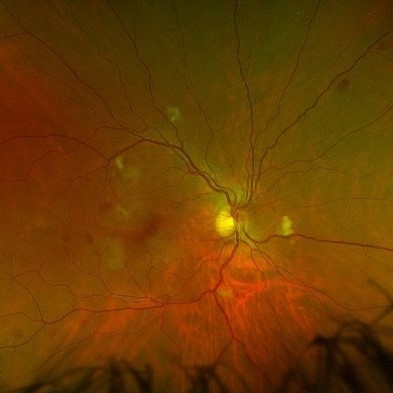

Widefield fluorescein angiography (Fig 3) demonstrated areas of non-perfusion, capillary obstruction and enlarged foveal avascular zones on both eyes, plus patchy peripheral non perfusion. Retinal vessels at the posterior pole as well as the peripheral demonstrated microaneurysmal changes. While there was no leakage at the macula and no widespread vascular leakage, peri-foveal capillary leakage in the late frames was seen.

Fig 3. Widefield fluorescein angiography demonstrating areas of non-perfusion, capillary obstruction and enlarged foveal avascular zones on both eyes

The retinal findings were thought to be linked with thrombotic microangiopathy and clinically represented a Purtscher’s-like retinopathy. With the inner retinal loss and established vascular changes on OCT, the patient’s visual symptoms were unlikely to resolve. Efforts were directed at identifying cause of the thrombocytopaenia and microangiopathy and minimising risks of recurrence. Despite extensive investigation, the patient is thought to have an atypical haematological issue and the exact diagnosis remains unclear.

Fig 4. OCT angiography (Left eye, from right to left: superficial, deep and avascular layers) better captured the extensive non-perfusion in the macula area in both the inner and deep capillary plexuses.

Discussion

A number of fundus findings can accompany haematological diseases and it is important to consider a wider differential than the common retinal vascular conditions, especially if there is corroborating history. Sometimes, it can be the ocular findings that lead to the systemic diagnosis.

Common clinical findings that accompany blood disorders include retinal haemorrhages and cotton-wool spots, but venous tortuosity, ischaemia retinopathy and optic disc swelling have also been seen. In the context of anaemia and thrombocytopenia (as was the case in this patient), one prospective study found the prevalence of retinopathy to be 28% and up to 44% if both are present1. For thrombocytopenia, no association has been found between the occurrence of retinal haemorrhage and age, the degree of thrombocytopenia or the cause of it2.

The exact mechanism leading to these changes is not completely understood. Retinal haemorrhages are explainable where there is a clotting problem, but our patient had co-existence of both haemorrhagic features. Rarely has a Purtscher’s-like retinopathy been described in the context of thrombocytopenia.

Purtscher’s retinopathy is associated with non-ocular trauma, classically compression injury resulting in a group of findings including cotton-wool spots, retinal haemorrhages, optic disc oedema, and Purtscher flecken (areas of inner retinal whitening). When typical retinal findings occur in the absence of trauma, the term Purtscher’s-like retinopathy is used. The cotton-wool spots are confined to the posterior pole and there are only a few scattered haemorrhages.

The generally accepted pathophysiology of Purtscher-like retinopathy is vascular endothelial damage and arteriolar precapillary occlusion by emboli, which can be of leukocytes, fibrin, fat and complement aggregates. This retinopathy is mostly seen with acute pancreatitis, renal failure, autoimmune diseases and thrombotic microangiopathies, as was the case with this patient.

Multimodal imaging can be useful. Capillary-flow voids at both superficial and deep capillary plexus are visualised by OCT-A. Fluorescein angiography showed multifocal filling defect and irregularly enlarged foveal avascular zone. OCT in the acute phase can show hyper-reflectivity of the inner/middle retinal layers, followed by loss of the inner retinal thickness with time, as was the case with this patient. Disturbance of macular ellipsoid zone on OCT has also been noted, which might be associated with a poor visual acuity3.

Management is controversial and the most important aspect is to identify and treat the underlying cause. This holds for both management of thrombotic microangiopathy as well as Purtscher’s-like retinopathy from any cause. Much of the ocular management is supportive. For Purtscher’s-like retinopathy, high-dose intravenous corticosteroids has been tried with the intent of partially restoring nerve fibres that had not been irreversibly damaged; however, a systematic review did not find statistically significant differences in the improvement of visual acuity when comparing steroid treatment to observation4.

While retinal haemorrhages and cotton-wool spots are common findings often associated with common retinal vascular causes such as vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy and hypertensive retinopathy, they can also be signs of significant haematological diseases. It is important to get an adequate history and keep an open mind for these possibilities.

References

- Carraro M et al. Prevalence of retinopathy in patients with anemia or thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol. 2001 Oct;67(4):238-44.

- Saadé M, Haddad F, et al. The role of funduscopy in severe thrombocytopenia: A prospective study, Transfusion Clinique et Biologique 2022 May;29(2):138-140. Epub 2021 Dec 16.

- Xiao W, He L et al. Multimodal imaging in Purtscher retinopathy. Retina. 2018 Jul; 38(7): e59–e60. Published online 2018 Jun 14.

- Miguel AI, Henriques F et al. Systematic review of Purtscher's and Purtscher-like retinopathies Eye, 27 (1) (2013), pp1-13

Dr Narme Deva is a consultant ophthalmologist at Eye Institute, Greenlane Clinical Centre and Retina Specialists in Auckland. She spent several years at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London and holds a doctorate of medicine from the University of Auckland for research into ocular wound-healing modification.