Update on scleritis

Scleritis is inflammation of the sclera and deep episcleral vessels. It typically presents with a deep aching pain, not responding to simple analgesia and sometimes waking the patient from sleep. Scleritis is an uncommon cause of red eye, but vital to diagnose, as untreated it may be vision (or globe) threatening, and a diagnosis of scleritis may point the clinician towards the diagnosis of an underlying systemic disease. Scleritis may be classified by location (anterior/posterior), appearance (nodular/diffuse/sectoral), presence of occlusive vasculitis (necrotising/non- necrotising) and aetiology (infectious/non-infectious/surgically induced)1.

Anterior scleritis typically presents as a painful red eye. The affected vessels are large calibre from the deep episcleral plexus and don’t blanch with phenylephrine. There may be a violaceous hue – the best way to see this is to look at the patient under natural light. Inflammation in scleritis may be sectoral, diffuse or nodular.

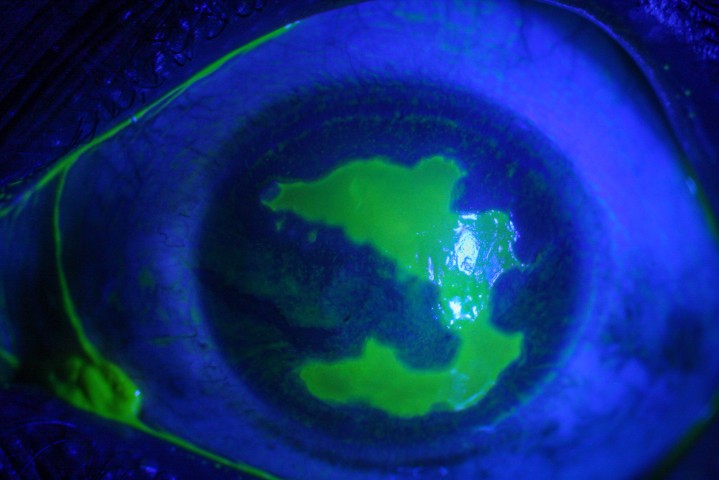

Fig.1 Anterior non-necrotising scleritis

Always check carefully for necrotising scleritis as this can be subtle in the early stages. If in doubt, it can be useful to look with a green light and also to check for fluorescein staining over the conjunctiva.

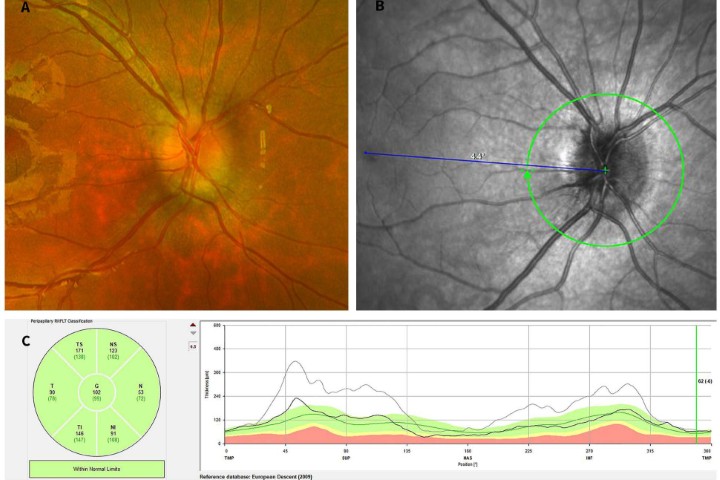

Posterior scleritis usually presents with periocular pain and headache or with symptoms of associated anterior scleritis. Vision loss is present in one third of patients2. The clinical presentation is more varied than anterior scleritis and may include serous retinal detachment, swollen optic disc, subretinal localised granuloma, choroidal folds and scleral thickening on transverse section B-mode ultrasound scan (B-scan).

Fig. 2 Posterior scleritis showing choroidal folds and exudative retinal detachment

Aetiology

In up to 50% of cases, scleritis is associated with a systemic autoimmune disease. The differential diagnosis for this is wide, but most common are rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously known as Wegener’s granulomatosis) and other ANCA-associated vasculitis, seronegative arthritis (including ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis), inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and relapsing polychondritis1. The clinician first seeing a patient presenting with scleritis is able to play a vital role in screening for associated autoimmune disease, arranging appropriate tests and, where necessary, referring to appropriate subspecialists for further evaluation. History should include previous ocular history including trauma or surgery, topical corticosteroid use, known medical conditions and also a thorough systems review. Medication history should also be taken, as scleritis may be associated with bisphosphonate use1.

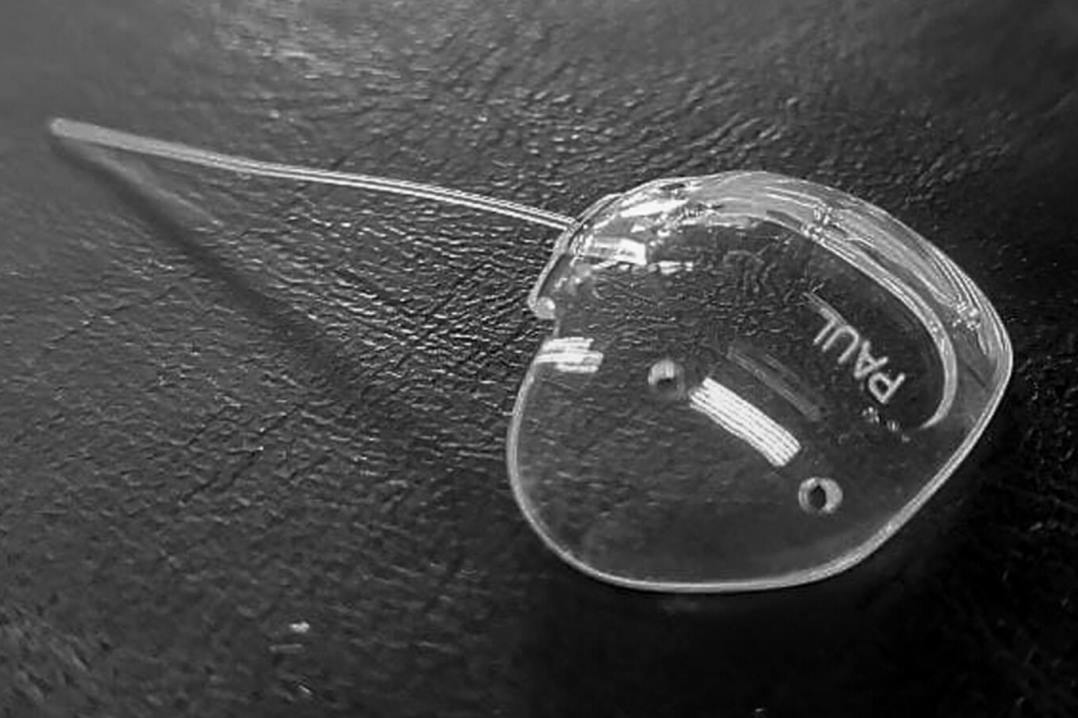

Surgically-induced necrotising scleritis is a rare complication of surgery to the eye, particularly following pterygium excision, cataract surgery and scleral buckling3. A similar presentation may also occur following ocular trauma. Patients typically present with necrotising anterior scleritis, with the site of inflammation usually situated around the surgical wound. Presentation may be significantly delayed, ranging from day one to many years following surgery, with the mean around six months3.

Fig. 3 Surgically induced necrotising scleritis following diabetic vitrectomy

Whilst most scleritis is immune mediated, around 5-18% of scleritis may be infectious. It is important to identify these cases to allow treatment of the underlying infection and to avoid clinical worsening from inappropriate use of immunosuppression. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common organism, particularly following trauma, however multiple other organisms may be implicated, including fungi, mycobacterium species and also viruses such as herpes zoster and simplex. Red flags that should alert the clinician to the possibility of infection include: history of prior trauma or surgery, although there may be a long delay to presentation; use of topical corticosteroid prior to presentation with scleritis; other immune compromising conditions such as diabetes, necrotising scleritis and scleral abscess formation; and pronounced anterior chamber inflammation and hypopyon4. Diagnosis is often delayed in infectious scleritis and organisms may be difficult to culture, frequently requiring scleral biopsy.

Fig. 4 Fungal scleritis with hypopyon

In rare cases, malignancy may mimic scleritis and this should always be considered in atypical presentations and in treatment-resistant cases. The most common masquerades are choroidal melanoma, conjunctival tumours and extranodal lymphoma1.

Management

Early scleritis may respond to topical corticosteroid treatment, however, most cases will require additional systemic therapy, either oral non-steroidal (NSAID) treatment or oral corticosteroid. NSAIDs are reported to be effective at resolving around 80% of anterior non-necrotising scleritis. Corticosteroids are used for subjects with posterior scleritis, necrotising scleritis and those who have failed oral NSAIDs. A typical oral dose would start at 1mg/kg, tapering over around six weeks. Those with vision threatening disease require admission for intravenous methylprednisolone 1g/day for three days followed by high-dose oral steroid1. Similar to other necrotising scleritis, SINS requires high-dose oral or intravenous corticosteroids and almost half will require second line immunosuppression3.

Indications for second-line immunosuppression in scleritis include: 1) unable to taper prednisone to ≤ 7.5mg/day; 2) intolerable side effects from oral prednisone; 3) anticipated long course of oral prednisone; 4) specific disease known to have a poor outcome with steroid treatment alone (such as GPA, rheumatoid arthritis, necrotising scleritis).

Infectious scleritis usually requires combined medical and surgical management, with only 1/5 responding to medical treatment alone. Both topical and oral antimicrobials directed towards the causative organism are needed and drug penetration is poor through the avascular sclera. Surgical management is important in providing a microbial diagnosis, debulking a scleral abscess, debriding necrotic tissue and removing any foreign bodies that may serve as a nidus for infection, such as a scleral buckle or glaucoma drainage device4.

What is new in scleritis

Biologic drugs are a powerful new treatment modality in scleritis and increasing reports show effectiveness in treatment-resistant cases. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α is a cytokine and inflammatory mediator that plays a role in uveitis and scleritis. Specific blockade of TNF with infliximab (intravenous infusion approximately every six weeks) or adalimumab (subcutaneous every two weeks) can markedly reduce inflammation and allow tapering of oral prednisone. Another biologic agent, rituximab, has also shown great promise in the treatment of refractory cases. Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody directed against CD20 B-lymphocytes. Treatment consists of two 1g infusions at day one and day 15 and results in a drop in B-lymphocyte population for around six months, frequently with considerable improvement in inflammation, and is particularly effective in patients with GPA/ANCA-associated vasculitis5. Current results from retrospective case series have been promising, but further randomised, controlled trials are needed.

References

- Daniel Diaz J, Sobol EK, Gritz DC. Treatment and management of scleral disorders. Survey Ophthalmol 2016;61:702-717.

- McCluskey PJ, Watson PG, Lightman S, Haybittle J, Restori M, Branley M. Posterior scleritis: clinical features, systemic associations, and outcome in a large series of patients. Ophthalmol 1999;106(12):2380-6.

- O’Donaghue E, Lightman S, Tuft S, Watson P. Surgically induced necrotising sclerokeratitis (SINS) – precipitating factors and response to treatment. Brit J Ophthalmol 1992;76(1):17-21.

- Murthy SI, Reddy JC, Sharma S, Sangwan VS. Infectious scleritis. Curr Ophthalmol Rep 2015;3:147-157.

- Cao JH, Oray M, Foster CS. Rituximab in the treatment of refractory non-infectious scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;166:207-208.

About the author

Dr Rachael Niederer trained in ophthalmology in New Zealand, receiving the Howsam Medal for Excellence, the Vice-Chancellor Best Doctoral Thesis Award and the Sir William McKenzie prize in ophthalmology. She subsequently completed her fellowship training in uveitis at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London. She now works at Greenlane Hospital, Auckland, as a uveitis specialist.