Vitreous floaters

The vitreous gel fills the posterior segment of the eye and has a volume of about 4ml. It is composed of 98% water and 2% structural proteins and extracellular matrix components. Collagen is the major protein, particularly type II (75%) and type IX (15%) with hyaluronan, chondroitin sulfate, fibrillins and opticin comprising the remainder of the proteins.

Hyalocytes are mononuclear cells embedded in the posterior vitreous cortex, 20-50 microns from the internal limiting membrane (ILM) of the retina, maintaining the synthesis and metabolism of the glycoproteins¹. The vitreous gel has strong adhesions to the pars plana and peripheral retina (at the vitreous base), the optic disc, macula and retinal vessels. Vitreous floaters are generally microscopic collagen fibres within the vitreous that tend to clump and cast shadows on the retina, appearing as floaters to the patient².

Causes

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is the most common cause of floaters, usually occurring over 50 years of age. It is more frequent and happens earlier in life in myopic individuals. It occurs due to vitreous syneresis (liquefaction) and contraction of the collagen fibrils with age². The fibrils are intertwined within the vitreous and are attached to the surface of the retina. As they continue shrinking, the fibres break and this leads to the separation of the vitreous from the retina, creating free floating vitreous in the posterior chamber.

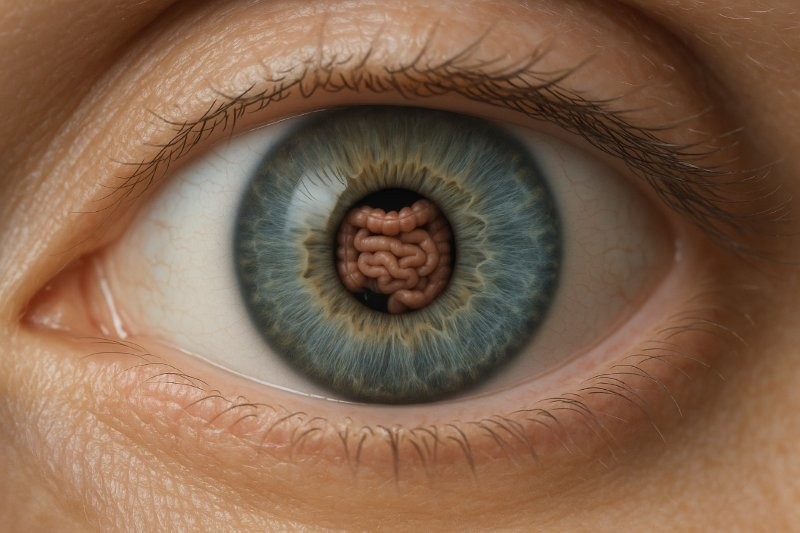

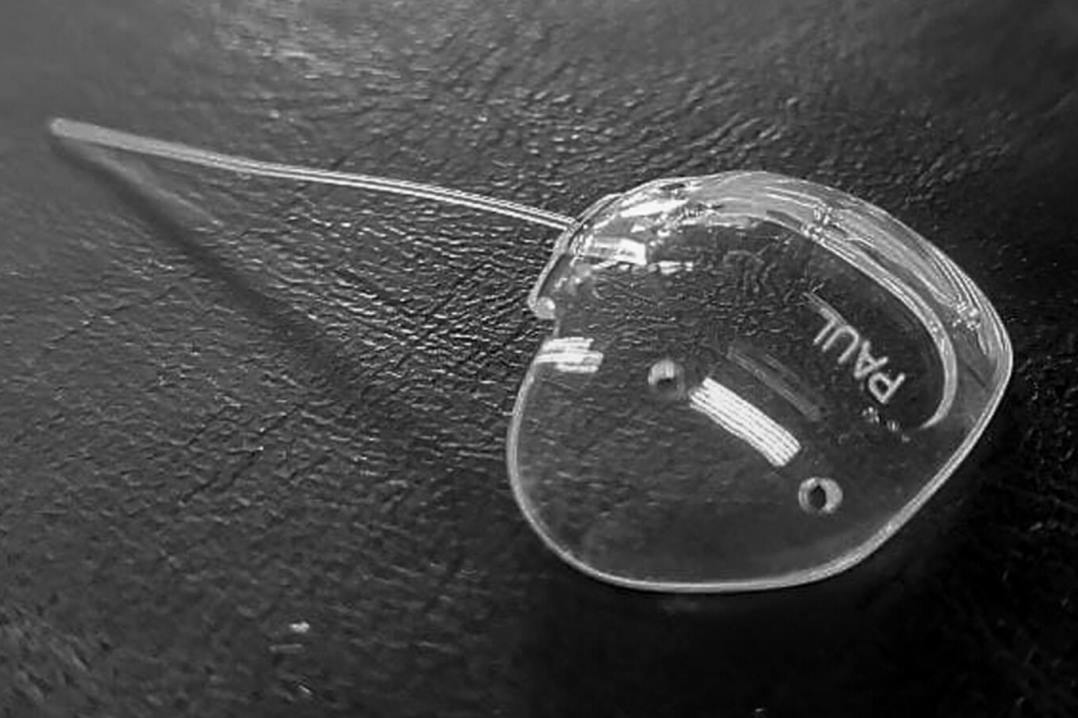

If this process happens gradually, the symptoms are typically mild and can go unnoticed. However, if the process is sudden, it can cause the release of strong attachments around the optic disc and a large symptomatic floater, known as a Weiss ring (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Weiss ring (arrow) associated with a posterior vitreous detachment

Vitreous haemorrhage (VH) can occur along with a PVD when the separation of the vitreous from the retinal vessels creates a break in one of the vessels. It may or may not be associated with a tear in the retina itself². VH can also occur due to the rupture of new vessels in the retina or vitreous which have developed secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy or ischaemic central or branch retinal vein occlusions.

Occasionally, it can also be caused by a large macular haemorrhage due to exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which has broken through into the vitreous cavity.

Uveitis. Intermediate or posterior uveitis causes release of inflammatory cells into the vitreous which can clump and cause floater symptoms. These usually arise from inflammation of the ciliary body, retina or choroid, which can be of infectious or noninfectious aetiology³.

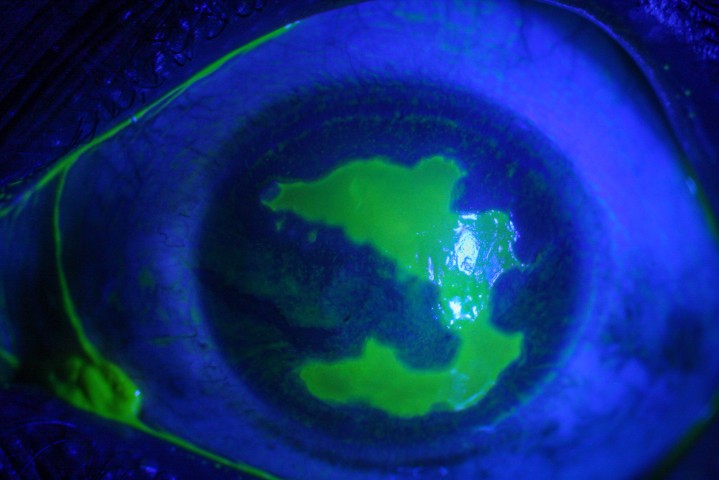

Asteroid hyalosis are small yellow or white refractile particles in the vitreous that increase with age and are distributed throughout the vitreous gel (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Dense asteroid hyalosis obscuring the view to the fundus

They are composed mainly of calcium and phosphorus with a structure similar to hydroxyapatite. The condition is usually unilateral (80.2-90.2% cases) and affects less than 2% of the population⁴. These eyes show abnormal vitreoretinal adhesion and rarely have a complete PVD. This is usually an incidental finding but may occasionally cause symptoms of floaters and need intervention to improve the view of the fundus. They may also cause opacification of silicone IOLs.

Intraocular tumours - choroidal melanoma, primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) or other metastatic and haematological malignancies can present with floaters and reduced vision³.

Presentation

It is important to assess whether floaters are acute or chronic and if any of the associated symptoms are present. Long-standing vitreous floaters are usually suggestive of vitreous syneresis and often young myopes may present with these symptoms.

Symptoms

- Flashes - usually associated with a PVD due to the traction from the vitreous fibrils on the peripheral retina as they are trying to separate from the retina

- Decreased vision - usually associated with a VH but maybe due to associated uveitis

- Photopsiae - choroidal melanoma may also be associated with photopsiae, often described as lava lamp light effects

- Pain - usually associated with uveitis but maybe absent in intermediate or posterior uveitis without any anterior segment involvement.

Examination

After recording the visual acuity, intraocular pressure and anterior segment examination, dilated fundus assessment is performed when a patient presents with floaters. The vitreous cavity may show syneresis when vitreous fibrils can be seen floating behind the crystalline lens. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy with a wide field lens is essential. Presence of a Weiss ring usually indicates completion of PVD. Careful examination of the peripheral retina can reveal any retinal tears or haemorrhages that maybe associated with the PVD. Vitreous cells are present in cases of intermediate or posterior uveitis. These are usually white cells in acute cases but can be pigmented when the uveitis is chronic. There may be clumping of vitreous into snowballs, usually denser in the inferior vitreous. The retina may also show areas of vasculitis seen as sheathing of blood vessels, retinitis (whitening of retina) or choroiditis (deeper yellow white lesions underlying the retina). If there is a dense vitreous haemorrhage, B-scan ultrasonography can assess whether there is any underlying retinal detachment. An OCT scan of the macula through mild vitreous haemorrhage can identify subretinal haemorrhage in cases of wet-AMD.

Management

Most cases with floaters either due to syneresis or PVD and no retinal tears or haemorrhage only need reassurance. With PVDs, however, a careful explanation of the process is required. The patient should be informed of the warning signs of retinal detachment, such as a sudden worsening of the floaters or flashes or loss of visual field that feels like a curtain is being drawn over the peripheral vision and advised to present urgently for examination in such an event. Any suggestion of VH or retinal tear or other signs of uveitis will require urgent referral to a retinal specialist or the acute eye clinic for further assessment and management.

Urgent laser retinopexy of any retinal tears is performed as an outpatient procedure. Rarely, the tear maybe very peripheral and require indirect laser retinopexy or cryopexy in the operating theatre. If there is more than one-disc diameter of subretinal fluid associated with a tear, it may not be suitable for laser treatment due to risk of progression to a retinal detachment and would require either a pneumatic retinopexy or vitrectomy surgery as a more definitive treatment.

Vitrectomy for floaters

The majority of patients get used to floaters related to a PVD, a few weeks to months after the initial event. The neural processes in the brain adapt to be able to ignore the shadows cast by the floaters and they become no longer bothersome to the individual. Occasionally, however, the floater is quite large or in the central visual axis and, if a person has quite high visual requirements, can continue to be annoying or even debilitating for daily functioning. Sometimes they can also cause severe glare symptoms due to diffraction of the light off the vitreous fibrils in the eye.

In these rare cases, vitrectomy surgery for removal of the floaters can be performed. With modern small gauge vitrectomy techniques, this is a fairly safe procedure and provides immediate relief of the symptoms. However rare complications of postoperative retinal detachment and endophthalmitis have been reported5,6. Hence surgery should be restricted for highly symptomatic cases who are unable to continue with their daily living activities.

Laser vitreolysis

Nd:YAG laser lysis of vitreous floaters, particularly a large Weiss ring, has been reported to subjectively improve symptoms, with a randomised control trial showing a 54% improvement in self-reported floater-related disturbance in treated cases compared with only 9% in sham treated controls⁷. However, the American Society of Retina Specialists Research and Safety in Therapeutics (ASRS ReST) committee reported a high risk of complications, such as elevated intraocular pressure leading to glaucoma, cataracts, including posterior capsule defects requiring cataract surgery, retinal tear, retinal detachment, retinal haemorrhages, scotomas and an increased number of floaters⁸. Hence extreme caution should be exercised in undertaking this procedure.

Concluding remarks

In summary, vitreous floaters are usually benign shadows cast by clumping of vitreous fibrils on the retina. Acute floaters require thorough clinical examination to eliminate associated retinal pathology such as tears, retinal detachment or, rarely, uveitis or exudative AMD, which would require urgent intervention.

Most cases do not require any ongoing follow-up or management as the symptoms of floaters are frequently self-limiting and rarely severe enough to require surgical treatment.

References

- Schachat, A.P.a., et al., Ryan's retina.

- Bergstrom, R. and C.N. Czyz, Vitreous Floaters, in StatPearls. 2018: Treasure Island (FL).

- Foster, C.S.e.o.c. and A.T.e.o.c. Vitale, Diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. Second edition. ed.

- Jablonska, A., J. Ciszewska, and D. Kecik, Asteroid hyalosis--current state of knowledge. Klin Oczna, 2014. 116(4): p. 272-6.

- Hahn, U., F. Krummenauer, and K. Ludwig, 23G pars plana vitrectomy for vitreal floaters: prospective assessment of subjective self-reported visual impairment and surgery-related risks during the course of treatment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2018. 256(6): p. 1089-1099.

- Lin, Z., et al., Surgical Outcomes of 27-Gauge Pars PLana Vitrectomy for Symptomatic Vitreous Floaters. J Ophthalmol, 2017. 2017: p. 5496298.

- Shah, C.P. and J.S. Heier, YAG Laser Vitreolysis vs Sham YAG Vitreolysis for Symptomatic Vitreous Floaters: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol, 2017. 135(9): p. 918-923.

- Hahn, P., et al., Reported Complications Following Laser Vitreolysis. JAMA Ophthalmol, 2017. 135(9): p. 973-976.

Dr Monika Pradhan is a consultant ophthalmologist at Greenlane Clinical centre, Manukau Superclinic and Eye Surgery Associates and visiting specialist at Re:Vision and Retina Specialists in Auckland, with subspecialty expertise in medical retina and vitreoretinal surgery. She has trained in India, UK and New Zealand and hold gold medals in various ophthalmology examinations.