Why are Pacific people in Aotearoa New Zealand disadvantaged in eyecare?

Aotearoa New Zealand’s population of 5.1 million people is growing at a rate of 2.3%. Over 40 Pacific ethnicities are represented, each with their own culture, language and history. The country’s 2013 census recorded 295,941 Pacific peoples, correlating to 7.4% of the population – an increase of 11.3% in less than a decade. Currently, New Zealand is home to 381,642 Pasifika peoples1, 60% having been born in Aotearoa. More than 8% of the population identifies as being of Pacific origin.

The Ministry of Health recorded two thirds (65.9%) of the country’s Pacific people reside in the Auckland region, with just over 35% of Pasifika enrolled in the former Counties Manukau District Health Board. The trajectory of population growth and improvement of disability-adjusted life years (DALY), exemplified in longer life expectancies for Pacific people, supports ongoing attention to Pacific health in a culturally appropriate manner to enhance quality of life and improve the health status of the entire population.

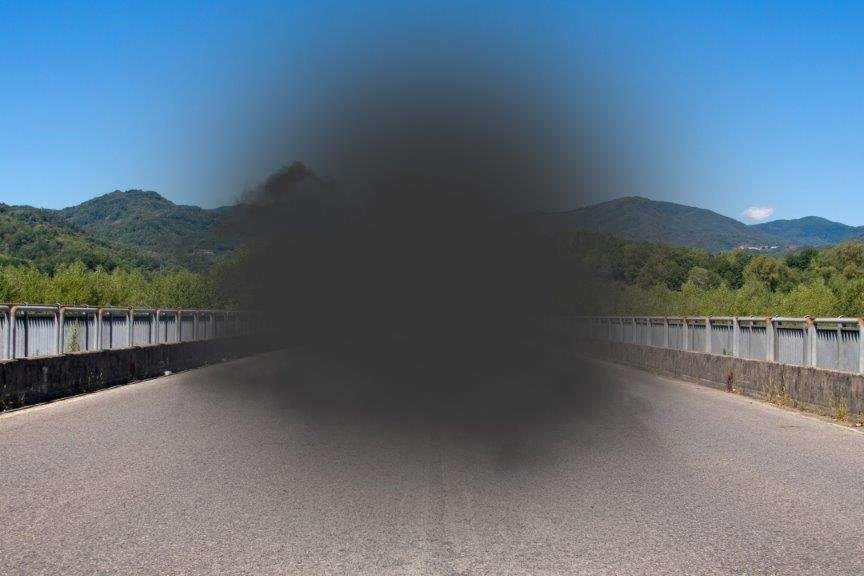

Fig 1. Advanced keratoconus with a stromal scar related to hydrops prior to presentation

However, Pasifika still have a shorter life expectancy in comparison to the general population. Over a third of the Pacific population (35.7%) is under 15 years of age, compared to only a fifth (20.4%) of the total New Zealand population. Interestingly, keratoconus is often associated with a family history, Māori (affecting 1 in 45 adolescents) and Pacific ethnicity, typically presenting in the second decade of life (Fig 1 and 2). Therefore, high rates of this condition are seen in young Pacific populations. Crucially, keratoconus patients of Māori and Pasifika ethnicities attended only 60% of offered appointments (compared to 90% for European and Asian ethnicities). Timely treatment can prevent progression, visual loss and requirement for corneal transplant (Fig 3 and 4)2.

Fig 2. Slit-lamp image demonstrating the dramatic coneshape of the cornea in advanced keratoconus with marked central thinning and an apical anterior stromal scar

Identifying inequities and barriers in eyecare

Eye health workers in Aotearoa New Zealand need to further identify and explore barriers experienced by Pasifika and Māori seeking eyecare and preventative screening, to better understand how inequities can be addressed.

In a study investigating Pacific childhood visual impairment, less than a fifth of children (15.2%) and teens (18.8%) reported having sought eyecare at least once (for children) or within the last two years (for teens). Refractive correction was needed in 3.6% and 14.3% of children and teens, respectively, and few of those needing correction had regular eye exams. This suggests improved access to services would correct or avoid much of this visual impairment3.

Fig 3. A clear 8mm diameter transplant within an 11.5mm host cornea is visible following corneal transplantation. The 16 pairs of white dots represent pinpoint scars from the interrupted

sutures initially used to secure the transplant

Māori and Pacific people residing in Aotearoa typically experience worse health outcomes in comparison to other ethnicities in New Zealand4. Services which remain inaccessible breed inequity. For decades, Pacific people have experienced poorer access to key determinants of health, such as quality education, equitable income and well-insulated and ventilated housing. While many advances have been made to the improve health and wellbeing of vulnerable groups, there are still barriers continuing to influence access to healthcare for Māori and Pasifika. Key barriers direct affecting uptake and access of health services are health literacy, language, and affordability.

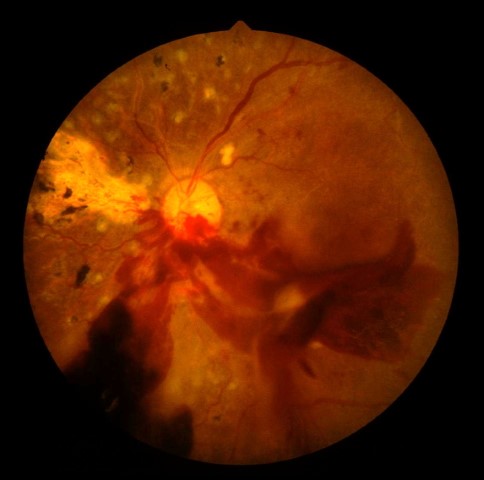

Fig 4. Severe diabetic retinopathy: haemorrhages, hard exudates, micro-aneurysms, neovascularisation and blood in the vitreous (despite earlier pan-retinal laser

photocoagulation)

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions5. Low health literacy has been identified as the ‘silent killer’ underlying many undiagnosed medical conditions. It can also result in poor adherence to treatment regimens, which poses significant problems after corneal transplantation, the ultimate treatment for advanced keratoconus. Non-compliance with medication and medical advice due to health illiteracy is more likely to increase morbidity and escalate healthcare costs for individuals and an already over-burdened health system6.

Currently, most Pasifika speak English fluently (89%) and 50% report being bilingual with English and a Pacific language. However, English was not a common language among Pacific peoples when they migrated to New Zealand in the 1950s, causing significant language barriers in occupation, education and healthcare. Interpreters are recommended between patient and healthcare providers if no family support person can confidently translate. Misunderstanding of patient symptoms or medical diagnosis can result in inappropriate treatment7. Free interpretation and translation services are currently available in Counties Manukau District Services; however, knowledge around how to access this service and how to incorporate it into an individual’s care plan is scarce in the community.

In public health, we continue to see rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases rise in Pasifika and Māori, whose uptake of health resources is disproportionately low. Interestingly, Māori present with cataract typically at a younger age and more advanced, and thus lower visual acuity than European New Zealanders.

To ensure Māori and Pasifika patients and family members receive care that is culturally safe, cultural awareness courses are available for health professionals. However, mainstream health systems, managers and services tend to overlook the relevance of these courses. Without prioritising implementation of what they teach, we fail to serve the direct need of marginalised populations in Aotearoa8.

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of blindness and low vision in New Zealand’s working-age population4. In a systematic review analysing diabetic eye disease and screening attendance by ethnicity in New Zealand, Pacific peoples and Māori had higher rates of sight-threatening disease and lower rates of screening attendance in comparison to European New Zealanders. Many Pacific families have found navigating the healthcare system challenging. Consequently, individuals only report to health services when chronic care is needed, rather than at primary stages of illness, incurring higher morbidity rates for Pasifika populations.

Identifying solutions

Until now, there has been no population-based eye health survey in Aotearoa New Zealand and eye health services do not generate routine monitoring reports. Therefore, the extent of eye health inequity in New Zealand is still largely unknown4. Clearly, mapping vision impairment in New Zealand related to demographics would greatly assist in targeting provision of future eyecare services9.

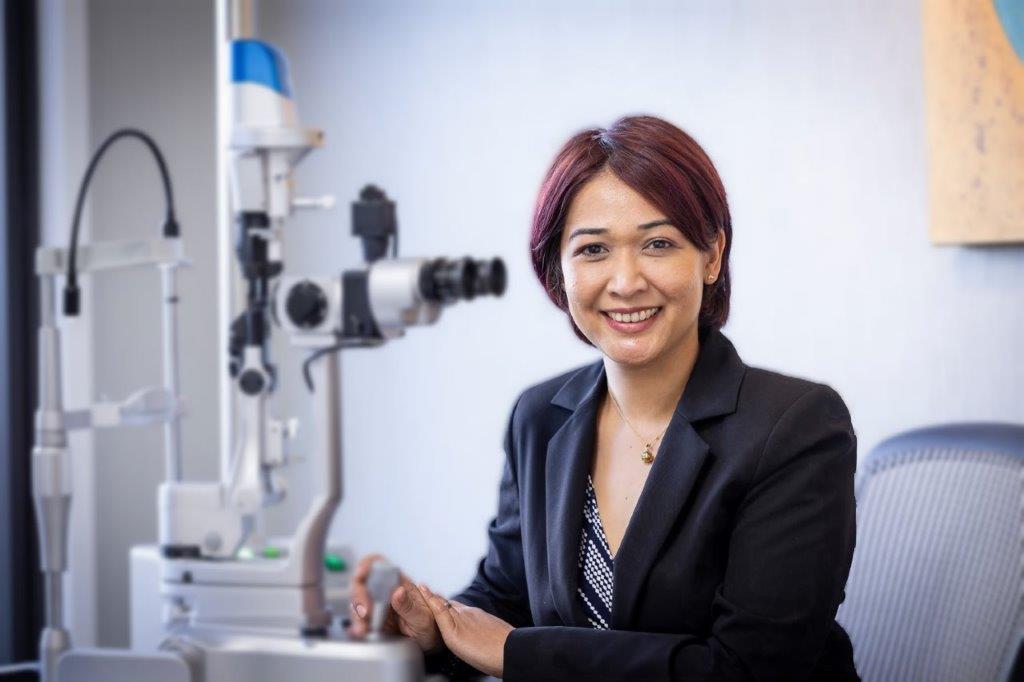

The author is embarking on PhD studies at the University of Auckland’s Department of Ophthalmology to address both the burden of eye disease in Pasifika and Māori and barriers to eyecare access in the greater Auckland region. This is part of a major multi-pronged five-year Visual Disability in Aotearoa project involving ophthalmologists, optometrists, public health specialists, epidemiologists and vision scientists with the specific intention of incorporating Pasifika and Māori researchers to make the best eyecare available to all Kiwis.

References

1. Aorere NZFAaTM. Pasifika New Zealand Available at: www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/pacer-plus/pasifika-new-zealand/

2. Goh Y, Gokul A, Yadegarfar M, et al. Prospective Clinical Study of Keratoconus Progression in Patients Awaiting Corneal Cross-linking. Cornea 2020;39(10): 1256-1260.

3. Hamm L, Johnson I, Jacobs R, et al. Visual impairment and its correction among Pacific youth in Aotearoa: findings from the Pacific Islands Families Study. NZ Med J 2021;134(1543): 39-50.

4. Rogers J, Black J, Harwood M, et al. Vision impairment and differential access to eye health services in Aotearoa New Zealand: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2021;11(9): e048215.

5. www.health.govt.nz/our-work/making-services-better-users/health-literacy

6. Crawford A, Krishnan T, Ormonde S, et al. Treatment adherence after penetrating corneal transplant in a New Zealand population from 2000 to 2009. Cornea 2015;34(1): 18-22.

8. Freundlich S, McGhee C. Should we be doing more to identify barriers to cataract surgery for Indigenous populations in New Zealand? Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020;48(7): 1014-1015

9. Gokul A, Ziaei M, Mathan J, et al. The Aotearoa Research Into Keratoconus Study: Geographic Distribution, Demographics, and Clinical Characteristics of Keratoconus in New Zealand. Cornea 2022;41(1): 16-22

Esmeralda Lo Tam is a youth and health advocate across Oceania and part of the business performance team at South Seas Healthcare. She was nominated for Global Impact and Social Enterprise awards in New Zealand as well as Forbes’ 30 under 30 for global social impact and represented Samoa at the 2018 Asia Pacific Youth Co:Lab Summit in Beijing.