Waiting for pseudophakia: an insider’s view of cataract surgery

We all know cataract surgery is no big deal. We refer patients all the time, reassuring them, reappraising them and sharing their delight when it all goes well, right?

Wrong! When it’s your eyes and your body, everything is a big deal. When you know a little bit about lots and nothing much about anything, the mind wanders into places it shouldn’t, finding ‘what ifs’ in every corner. Apart from an emergency Caesarian section 31 years ago (which was very successful, according to my youngest heir), I’d always been confident that nobody ever gets near me with anything surgical unless it’s a sight- or life-threatening crisis.

So, what am I doing, volunteering to become aphakic? Well, I discovered even minor cataract plus glare equals blur, loss of contrast sensitivity, difficulty reading, loss of confidence driving and general irritation. Yes, we have heard it all before, but it’s different when it’s your eyes and you have to hand the decision-making over to other people: a control freak’s worst nightmare!

Low-contrasting views

I started fitting multifocal contact lenses when they were first launched in New Zealand in 1996. My experience with monovision went back further. I think I had a pretty good handle on the advantages and disadvantages before multifocal intraocular lenses (IOLs) arrived on the scene, which incidentally was about the same time as I switched to seeing solely low-vision patients.

The idea of a lens in the eye, splitting the image, was not something I was prepared to contemplate for myself or anyone else. A contact lens can be removed and a pair of spectacles for occasional use to balance monovision is a no-brainer, if the brain can tolerate the initial imbalance.

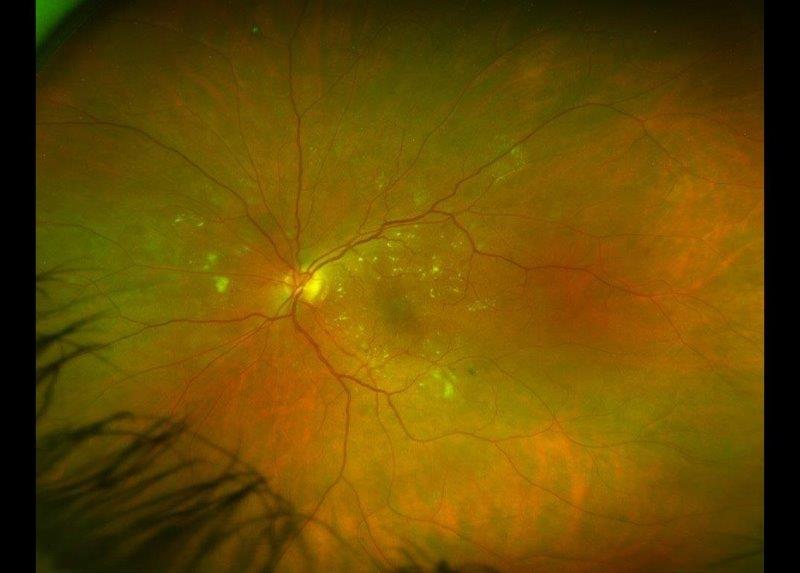

I decided long ago that multifocal IOLs reduce contrast, the most debilitating issue for my low-vision patients. Contrast sensitivity function (CSF) was something stuck in a past life of optics lectures, relegated to long-forgotten shadowy stripes and formulae, never fully understood and never intended to be useful – something best left in the past, I thought. But I now deal with this on a daily basis and have a better understanding of the functional consequences than I ever thought possible. Thus, in anticipation of joining the ranks of those with macular degeneration myself one day, I believe I need all the contrast I can get.

I was also getting used to wearing glasses, cursing the potential onset of dementia as well as presbyopia when I forget to carry a pair with me. It’s not vanity that drives me, just that it would be nice to retain some ability to read unaided in an emergency. Being able to read my phone or the car’s dashboard dials is important and I was always able to do so until the onset of cataracts!

Cloudy, but clearing later

So here I am, all drugged up waiting to lose my virgin lens. Is it too late to panic? No, there’s still plenty of time to panic.

I’d decided the right eye was to be sacrificed first, in case it all went bad. There are degrees of badness and I think I could cope with the lesser degree of badness and cataract in my dominant left eye for a bit longer. However, the surgeon’s plan is to do this ‘good’ left eye first.

So why am I agreeing to having a distance-only IOL in my better eye first? Because the surgeon – after checking functional vision priorities and lifestyle – carefully set out a management plan respectfully allowing me to feel I was in control of the decision making, even though the decisions had clearly already been made.

There is nobody as anxious as a control freak who knows they have not an iota of control left. I know our ophthalmologists do thousands of these cataract operations, but there are not thousands of my eyes: this pair has to last me a while yet.

I hope I don’t show how nervous I am; I hope I am completely knocked out and don’t know anything until it is all over, like a colonoscopy - the trick there is to walk in and then carefully place your dignity behind the pot plant beside the front door, remembering nothing else but to collect it again on your way out.

It was a weird feeling, watching the bright lights, knowing they were fishing around in my eye but feeling nothing. Just lie there and follow the light. Next minute, I was having delicious refreshments and waiting for my daughter to shepherd me home – a novel exchange of roles for us, marking the first of several surprises!

From yellow brick road to technicolor

Several hours later, I wake, pleasantly relieved at having no discomfort at all. However, peeping around the clear plastic shield, my skin, which had looked a pale bronze due to a miserable start to the summer, now looks a pasty pink. Through the operated eye the world looks incredibly white; colours are glowing and everything is super sharp. Through the un-operated eye everything looks bronze and sepia. The difference, not only in sharpness but in colour, is stunning!

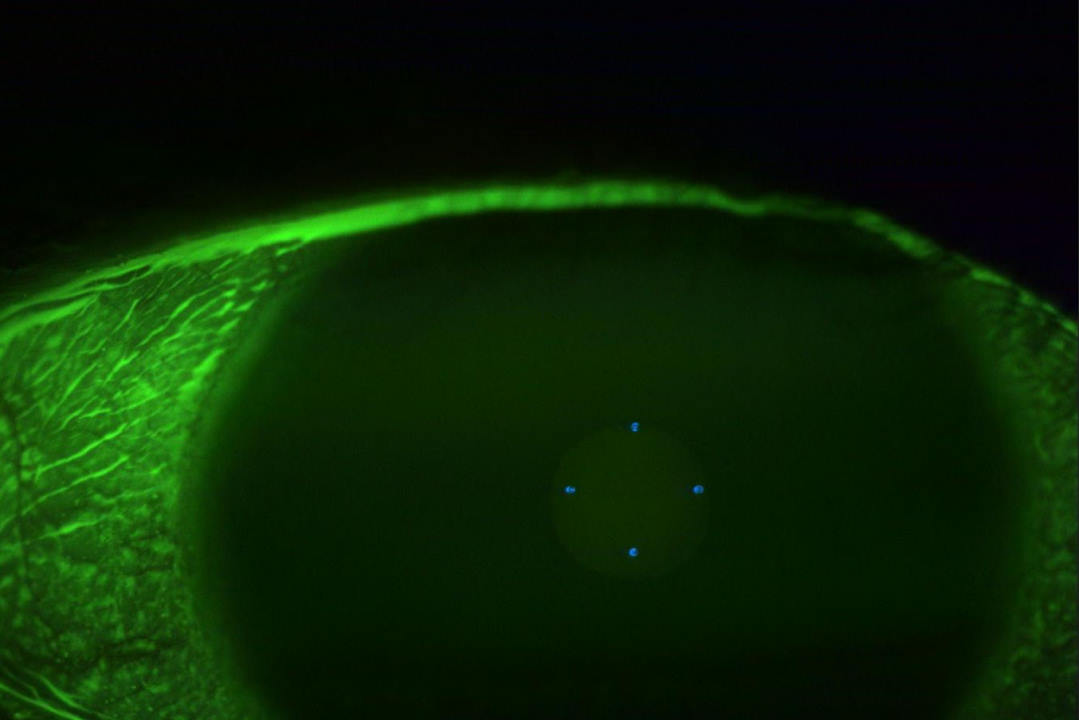

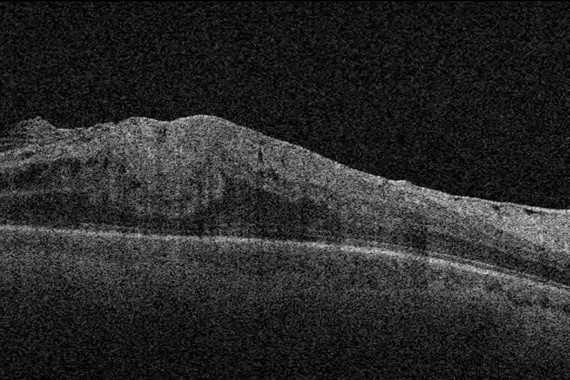

I don’t think I have ever seen as well as I do now with my new lens. Day-one follow-up and 6/4.8 vision; the signs on the motorway are crystal clear and I can read the dashboard dials and my phone easily through my new distance-only lens without spectacles. The surgeon told me this is the only lens to give such clarity and true colour because the design neutralises both the focal and chromatic aberrations of my peripheral cornea.

From one to two

I am going for an extended depth-of-focus lens (EDOF) in my right eye with ‘mini blended vision’ – offering a slightly myopic correction for distance plus ‘social vision’. I think that’s a rather sweet term for being able to read a menu without reading glasses (not my priority, but certainly useful).

My remaining lens had served me well over the years, only really failing me quite recently, and I was rather attached to it, so to speak. Bidding it farewell just 10 days later, I find it rather disconcerting to find I have no memory of my first operation’s shift from the pre-op table, where I chatted to the anaesthetist, to the operating room. When I comment on it this second time around, the team assures me I did move, explaining it’s common for the brain (or the drug) to blank out everything the first time. They also say the experience is similar to the effects of the date-rape drug, which does not make me feel any better.

Purple, without haze

Afterwards, with the benefit of the pinhole effect, my vision is 6/4.8 and N4 in good light on a high-contrast chart. I now feel confident that whatever the future holds in the way of macular degeneration or the like, I will not have compromised my contrast sensitivity or focus in either eye and, with an optical correction and the wonderful low-vision aids that are available, I will be able to cope.

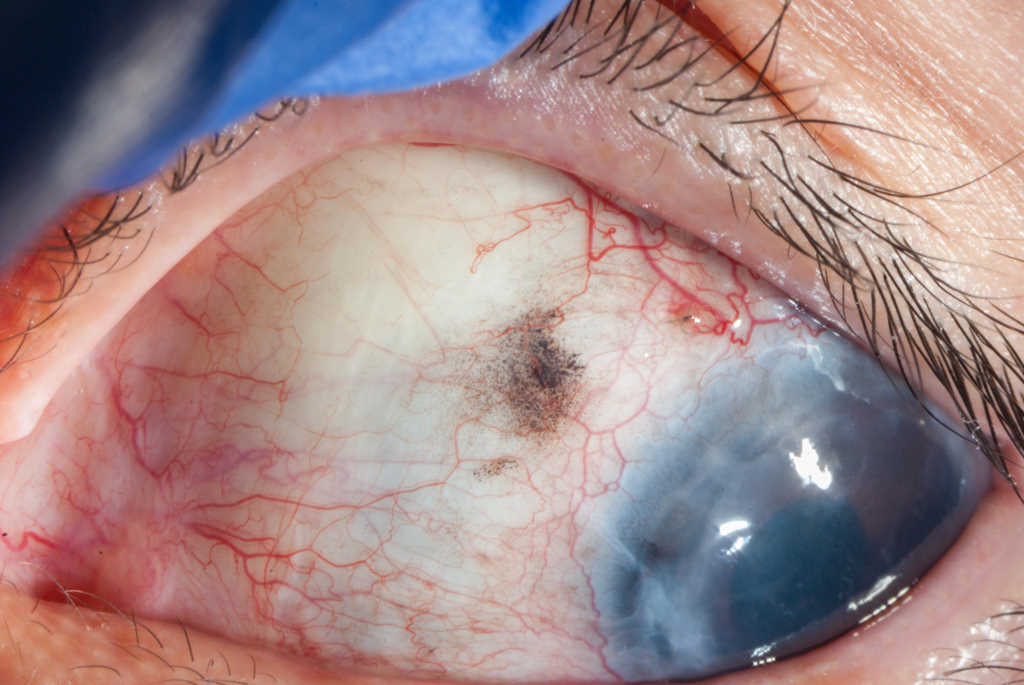

One strange effect remains: weird happenings in my colour vision. Certain things that used to be black or grey now have a purple hue. For example, a set of smokey grey glass bowls now looks smokey mauve and among items of black clothing that previously matched, some now have a slightly purple or even brown hue. Also, my various pairs of progressive spectacle lenses, with anti-reflection coatings, which used to all look colourless now appear to be different shades of yellow to greenish yellow. Looking at my NZ Optics year planner on the wall without spectacle lenses, there are blocks of mauve highlighted on a very white background, while through my spectacle lenses, only the darkest blocks of mauve remain and lighter blocks have disappeared into a slightly sepia background.

I have been assured that my new IOLs are totally colourless with no yellow filter. I can only assume that certain materials refract colours differently and the aberration-control IOLs are cancelling out my natural peripheral corneal aberration. So perhaps what I am seeing is more ‘true colour’ than I have previously seen.

The worst part of the experience is discovering my house-cleaning skills are not up to the standard I thought they were. And the bathroom mirror has been lying to me for years.

All in all, it was an incredibly positive experience and I am more than pleased with my resulting eyesight. But now I’m off to deep-clean the house and book a facial, or two!

Ed’s note: Naomi received an ultra-high definition Tecnis IOL in her dominant left eye and an EDOF in her right eye. Two months on, she says she continues to have very comfortable, normal-feeling vision but still prefers to wear glasses for extended reading periods and computer work. “It is just more comfortable, probably because with my glasses on, it restores the balance to use both eyes together.”

Naomi Meltzer has worked in optometry for more than 35 years and runs an independent practice in Auckland specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.