Book review: Low Vision: Principles and Management (first edition)

Book review: Low Vision - Principles and Management (first edition)

by Ana Hernandez Trillo, Christine Dickinson and Michael Crossland

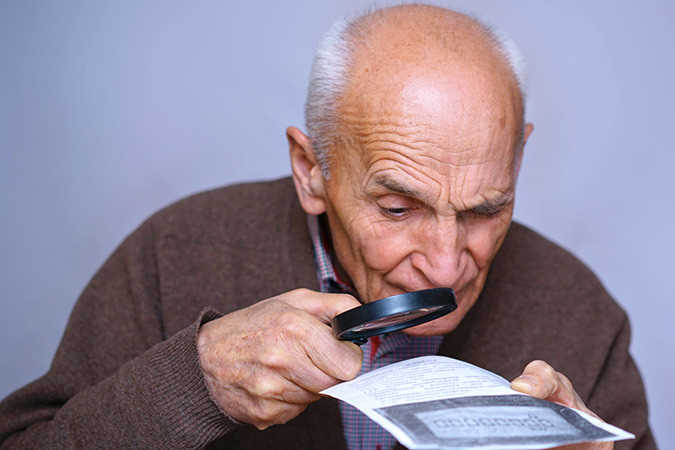

Finally, a textbook that references low vision in the 21st century! While not forgetting the theoretical aspects, the text provides a functional and practical guide, suitable for students or the experienced practitioner who occasionally encounters a low-vision patient in need of help and support. Even those who have specialised in this area for a long time will find useful updated information, particularly in the areas of rehabilitation and technology (though at the speed technology is moving, no text can ever be entirely up to date).

The authors, from Manchester University and Moorfields Eye Hospital’s Low Vision Clinic, UK, say that since this diverse topic spans ocular pathology, epidemiology, lighting, optical design, psychological adaptation and devices for sensory substitution, a general grounding in optometric and ophthalmological topics is assumed. Disease knowledge also allows the likely impairment to be anticipated, which helps in targeting questions about activity limitations.

Following the table of contents (helpfully divided into five parts, with each part divided into chapter subheadings), Low Vision’s authors launch into defining their subject, which is no mean feat. Instead of traditional definitions based on visual acuity on the distance chart, they characterise low vision in terms of visual impairment, activity limitations and participation restriction. They recommend thinking in terms of consequences to the bodily organ affected (the impairment), the consequences to the patient in terms of their abilities (activity limitation) and their interaction with the society they live in (participation restriction), with the aim of preventing activity limitation and participation restriction. Framing low vision this way lays bare the inadequacies of using the ubiquitous ‘legally blind’ label, which exists only to prevent benefit fraud.

A pragmatic view of visual performance testing is also highlighted by the statement that, “It should be emphasised that in the context of a low-vision clinic, tests with high diagnostic accuracy are not necessary: the aim is to discover whether there are functional consequences of a defect”. This reinforces the need to speedily gather enough information for the practitioner to be proactive about reducing activity limitations before the patient is fatigued and/or loses interest.

Illuminating info

While the chapters on lighting, glare and contrast start with scientific descriptions, the authors soon get into real-world situations. They suggest it’s important to test the effect of lighting individually, for example, rather than making assumptions concerning lighting conditions and a patient’s visual status or disease condition. I have to dispute the classification of glaucoma causing mild glare effect, however. In my experience, glaucoma patients can experience a range of glare discomfort up to a severity comparable to that of retinitis pigmentosa sufferers.

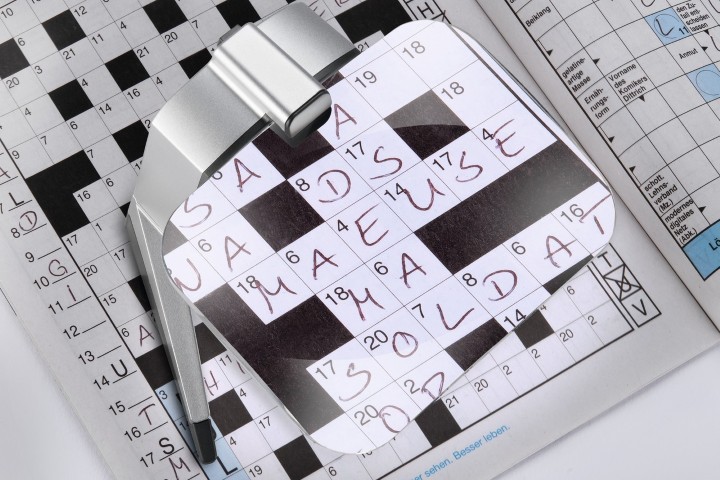

Discussing ambient illumination, the authors note Cullinan (1980) found the median level of ambient lighting he measured in patients’ homes was just 10% of that in the hospital clinic, meaning their real-world performance would be far worse than their assessment suggested. “Patients are unaware of how poor the lighting is in their home, so do not feel the need to change it,” he said. I would add that the practitioner who only tests with a high-contrast reading card in a well-lit examination room is not getting a real-world indication of activity limitation either!

The two chapters on aids and strategies for peripheral field loss cover a very difficult area which often brings in other rehabilitation professionals such as orthoptists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists searching for information. The chapter on inclusive and universal design is also excellent. Although it’s rare to find information on this topic, clinicians with a reputation for working with people with low vision are sometimes (but not often enough) called upon for advice in this vital field.

There ism however, a disappointing lack of information on paediatric low-vision care, other than a section on questions to ask a school-aged child to ascertain areas of activity impairment and social participation.

Summary

With tables used to clearly summarise key points and each chapter starting with an outline of what’s to follow, this is a very user-friendly reference manual which allows the reader to quickly zero-in on their area of interest for both optical and non-optical solutions. There is enough scientific content to satisfy the academic in a teaching role and plenty of good practical advice for the busy rehabilitation professional.

Naomi Meltzer is an experienced optometrist who now runs an independent practice in Auckland specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.