Case study: The reality beyond cataract surgery

At first glance, this appeared to be a 74-year-old man struggling with the aftermath of a transient ischaemic attack (TIA). The referral letter stated:

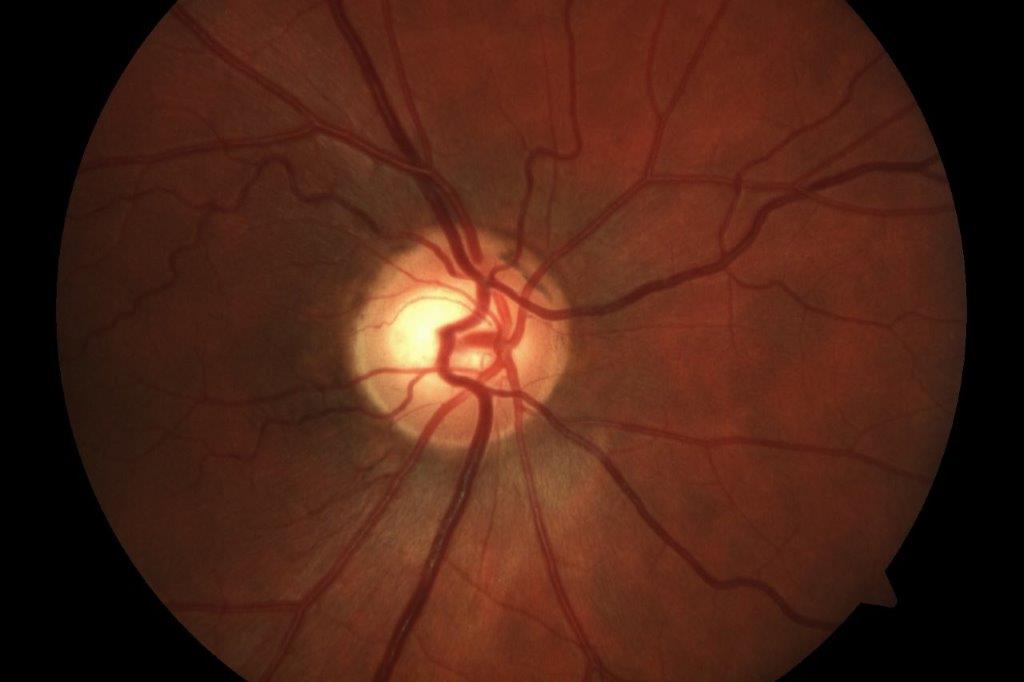

Ocular diagnosis

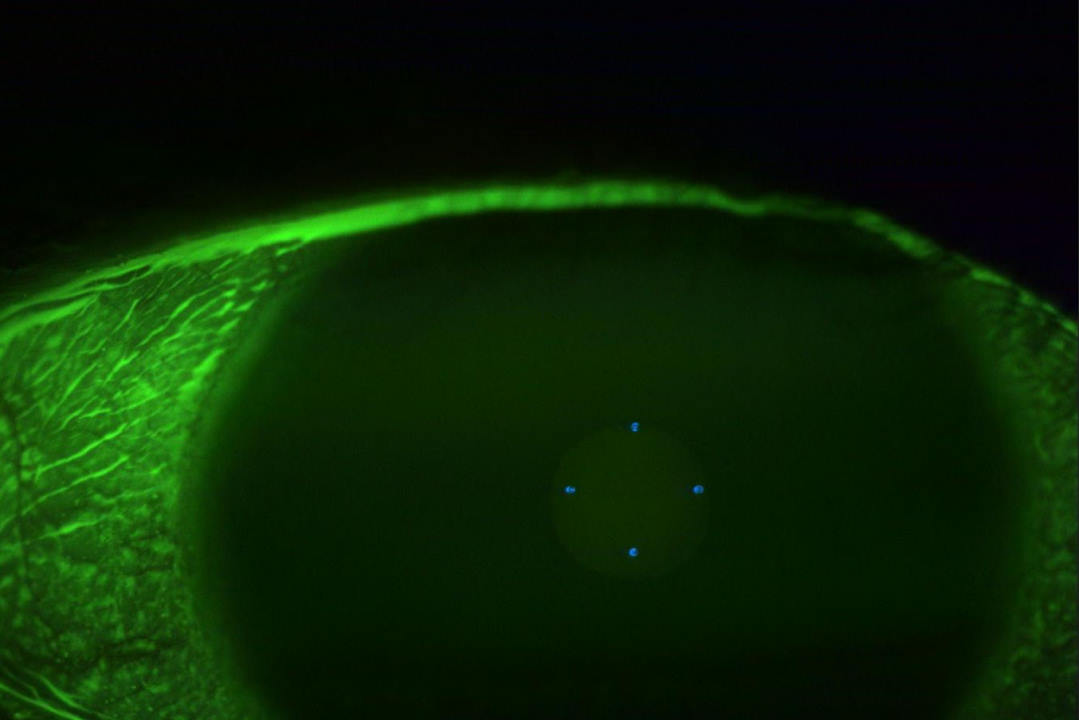

- Right homonymous hemianopia secondary to left occipital infarct, likely from intracranial atheroma and basilar stenosis

- Bilateral pseudophake

- Disc asymmetry, with no evidence of glaucoma

- Visual acuity, unaided: RE 6/7.5; LE 6/15.

Visual-field testing had revealed complete loss of vision in the right upper and lower quadrants. The referral letter said the patient had been informed that the loss of visual field is unlikely to recover and he had been encouraged to return to activities, “with adaptations for his visual-field loss”, for which he was being referred to me.

Thinking this sounded like a straightforward case of loss of contrast sensitivity due to neurological involvement and loss of peripheral vision, I started preparing a plan for assisting with better light and strategies for living with homonymous hemianopia.

However, something about my phone conversation with the patient made me suspicious that this wasn’t the only problem. This man was a keen walker and cyclist, but he didn’t seem to acknowledge a problem with his field loss, being more concerned that he was unable to concentrate on visual tasks such as reading or watching TV for more than half an hour, after which fatigue set in. Lookng at the TV was like looking through a watery panel, he said.

My suspicion went into overdrive when I mentioned his glasses and he was adamant that he did not wear them. Eventually he admitted that he used to wear glasses but no longer needed them since his cataract surgery. Perhaps this was the source of his fatigue? Perhaps the stroke had compromised his binocular co-ordination?

Acting on a hunch, I contacted the ophthalmologist and asked if they had any information on the patient’s visual history prior to the TIA, in particular from his cataract surgery. As luck would have it, the surgery had been done by a different ophthalmologist but at the same practice.

I felt like I had hit a hole-in-one when I received the information that bilateral cataract surgery had targeted “blended vision” – what we used to call monovision, with the right eye targeting distance and the left eye for near. Binocular distance acuity post-surgery was recorded as 6/7.5 and N6 for near.

When I started his assessment, to my absolute amazement, binocular functional visual fields and confrontation tests failed to find any signs of hemianopia or other restriction of visual field. The patient was totally co-operative and appeared to be concentrating and maintaining fixation on the target.

After several attempts, and feeling a little embarrassed, I revealed my failure to the patient. He calmly reported that a neurosurgeon a week earlier had also been unable to find any restriction in his peripheral vision. I have always understood that recovery is possible, but most takes place in the first three to six months. This was now almost a year since his first stroke and he had had several TIAs since. Perhaps all the swimming, walking, yoga and physiotherapy had aided a hasty regeneration of the oxygen-starved areas of the occipital lobe. Can anyone give me a better explanation?

So why the fatigue and discomfort?

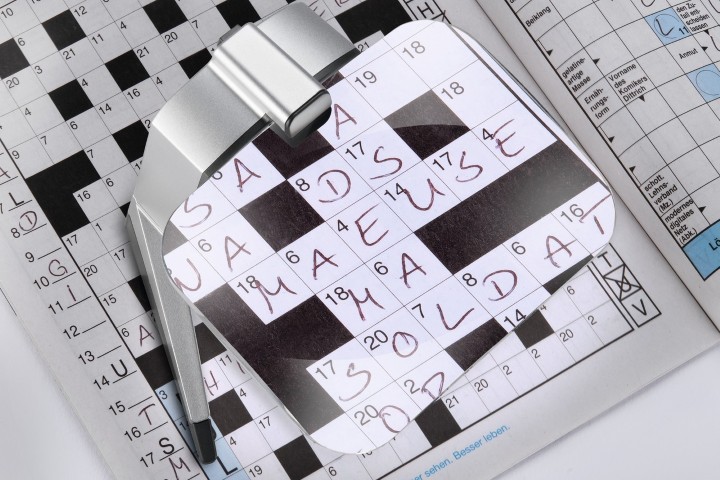

Binocular near acuity unaided was N6 on a high-contrast single-word chart in average room lighting. This improved to N4 with a task lamp and a continuous text reading chart. His low contrast acuity was N8, within normal range for his age.

Along with the details of his cataract surgery, I also requested the auto-refractor results post-surgery. These were: RE +0.12 -0.87 x 88; LE -1.50 -0.25 x 119.

Looking at the TV with a -1.50 DS lens over his left eye gave instant comfort and the ‘watery film’ disappeared. When a +1.50 DS lens was held over the right eye, he reported that the newspaper looked better. He could see it without the lens, but it felt easier with the lens, particularly when I put the reading lamp closer to the paper. Without the lens he needed to hold the paper at arm’s length. With the balancing lens he could read comfortably and fluently at approximately 40cm.

The message here is that just because a person can read the high-contrast letters on the distance chart or the smallest words on the near chart doesn’t mean they can sustain that ability to read comfortably and fluently, particularly when there are new challenges to their general or visual health.

It is understandable that patients experiencing liberation from spectacles after cataract surgery are delighted with their new vision and believe this is how it will remain forever. Whatever they were told by well-meaning and enthusiastic surgical staff is unlikely to be understood, let alone remembered down the track, when the vision is further challenged by general ageing and pathology such as macular degeneration, stroke, glaucoma or amblyopia. This is distressing for patients, even more so for those struggling to help them, often without the benefit of the relevant history. As time goes on, these cases are becoming more common and they are often very unhappy and confused people.

Post-surgery benefits of optical prescriptions

When things start to go wrong and the person has to rely on one eye, often swapping from dominant to non-dominant eye, a spectacle prescription that balances the vision and makes the best use of the remaining functional vision in a co-ordinated way may help to avoid falls or give comfort and overall functional improvement.

The problem is that years down the track nobody remembers the visual history with its chapters of functional, optical and medical events. Perhaps it’s time to consider a written record that must be kept by the patient and produced at future eye consultations or medical emergencies, where relevant information – eg. that expected unaided vision is worse in one eye than the other because it has a reading or multifocal IOL or a history of amblyopia, or pinhole pupils for reading, rather than being neurologically or drug-induced – could save a lot of time and grief.

The information needs to be standardised so that it is meaningful and easily interpreted by all, which means having relevant information, not just the brand and measurements of the IOL inserted. We would then have to find a way of impressing on each person that they need to carry this information on them at all times, particularly when travelling, perhaps using a phone app.

Naomi Meltzer is an optometrist who runs an independent practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.