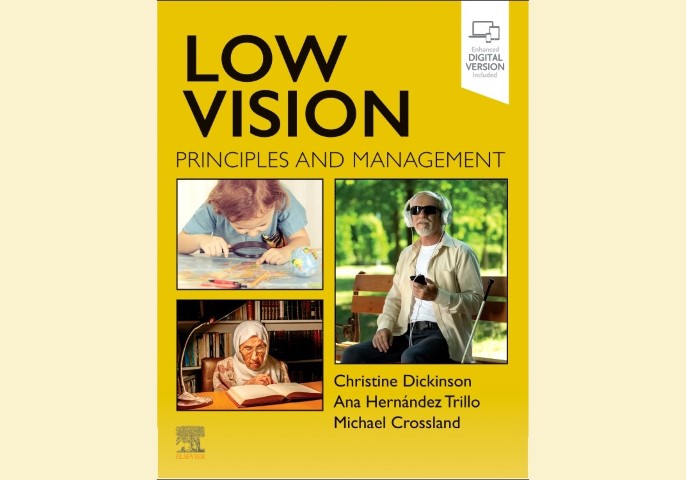

Low vision in the 21st century

Last century, low vision services were regarded as a last resort and an admission of failure. Generally, when patients enquired as to whether there was anything available to help them see, the answer was either a tentative, ‘you could buy a magnifier’ or a more defensive, ‘you’re not bad enough for that yet’.

When medical and surgical options ran out, the patient was dismissed with ‘there is nothing more that can be done, sorry’. This was effective at getting the patient out the door, but left them emotionally and physically stranded, unable to comprehend how to function visually when they were neither blind nor seeing. More patients were rendered functionally “blind” by this statement than by any other documented pathology and, sadly, many continue to exist in this state today, convinced this statement remains true as it was given by those they trusted.

For some, this attitude has continued into this century, despite huge changes in medical, optical and electronic technology, and the current view of low vision as a spectrum of functional changes that occur along the pathway between normal vision and no light perception. A few weeks after I started my low vision practice in 2011, I ran into an ophthalmological colleague who told me, ‘I hope you never get to see any of my patients!’ But for many, there has been a shift in thinking towards understanding that visual function cannot be defined by the size of letter read on a high-contrast distance chart or a monocular electronic visual field analysis; and visual rehabilitation does not mean restoring vision to normal, but the rehabilitation of a person with visual loss to function within their family, whanau, community or workplace.

Much of this change has been driven by the realisation that even with the amazing advances in medical science in the management of ongoing problems such as glaucoma, macular degeneration or other retinopathies, it is just that – management of the condition – not restoration of normal visual function. Thus, the best outcomes are obtained when patients are given as much information as possible on the range and type of additional services available to them sooner rather than later when all else has failed.

Today, the modern low vision consultation reviews how a patient with low or declining vision functions in their everyday environment and how we can help them use the vision they have more efficiently to manage their day-to-day activities. This involves taking a holistic view incorporating their general health, and the impact of perhaps other health problems such as stroke, Parkinson’s or diabetes on their visual functioning; and their physical environment – are they confined to one, poorly-lit room in a rest home or actively participating in sport or looking after other family members? Does their visual problem extend to passive reading or do they have other needs such as mobility or glare control? Is there a history of amblyopia, binocular vision instability or balance problems that has been forgotten along the way or considered irrelevant due to the patient’s poor distance acuity? Has the need for prescription glasses to focus at near range been overlooked as their vision deteriorated? Or do they perhaps simply need reassurance there are options available to help them if and when they need it?

A functional, low vision consultation helps assess each patient on an individual, case-by-case basis, going way beyond the ‘let’s see if a magnifier will help’ approach.

Recently, a request for assistance from a resource teacher brought home to me how much a bit of lateral thinking and a good stock of low vision aids can change an otherwise ordinary day. A 12-year-old boy with low vision due to retinopathy of prematurity, copes well in the classroom with just his spectacle prescription correcting his hypermetropia and high cyls plus a close-working distance to use his accommodation for extra magnification. However, given he was starting woodwork and sewing and would have to use sewing machines, fretsaws and grinding machines and the like, the resource teacher was on the hunt for some additional magnification for him.

She had found a magnifier attached to a goose neck stand, but this got in the way of the student and couldn’t be moved easily from one piece of equipment to another. The boy was also required to wear safety glasses for the woodwork equipment so an initial idea to use a head loupe was a non-starter, while a large magnifier on a tilting wire frame, ‘just got in the way’. We settled on a hands-free “embroidery” magnifier, which sits against his chest with a cord around his neck and is LED-illuminated. While only providing 2x magnification (he needs 3.5x to read a mm ruler) it was sufficient to help him see the needle or the blade of the saw at a normal working distance.

What was exciting however, was watching the student. He was like a kid in a candy store trying out all my high-tech and low-tech electronic stuff. In his lifetime, he will no doubt use way more high-tech aids than are available today, but this exercise at least showed both of us, how a simple low-tech, low-cost magnifier and a good dollop of lateral thinking can triumph. A very satisfying outcome all round.

After 30 years in general optometry, Naomi Meltzer realised her passion lay in visual rehabilitation and now runs an independent, low vision consultancy service in Auckland, New Zealand. She is a MDNZ founding trustee, a qualified CentraSight and eSight assessor and OrCam trainer.