RGPs and corneal graft patients

Adjoining the consulting room of my specialty practice, Bay Eye Care, is an office shared by a clinical psychologist and a private psychiatrist. Fortunately, none of my patients are yet to require their calming advice or a prescription of high-dose lithium to combat the irreparable psychological trauma of air-puff tonometry. It is nice to know, however, that these two guys are just a door knock away to assist with certain ‘interesting’ patients that we all see from time to time. Ortho-k lenses really won’t help your problem love!

During breaks at the water-cooler we often share tales from our work day. I regale them with stories of hideously irregular corneae and rampant myopia. They offer tragic anecdotes about mental illness and self-harm. Before returning to our desks to complete the stuff.co.nz daily quiz, we cheerily joke that we should never swap patients even for a day.

There is though, one group of corneae patients that contact lens practitioners frequently deal with that have a number of similarities to the mentally ill:

- They sometimes require heavy medication to control acute episodes

- They can be calm for years then rapidly degenerate to an angry, uncooperative mess

- They come in all shapes and sizes and no two are the same as they all have their own unique idiosyncrasies

- And, even though everything may seem fine, big problems can be lurking beneath the surface, unbeknownst to the subject in question

I am, of course, talking about corneal grafts patients.

An eye with a keratoplasty is frequently one of the most challenging to fit successfully with contact lenses. Unfortunately, these eyes are the ones often most in need of contact lenses due to anisometropia, high astigmatism or a highly irregular surface. Grafts are not uncommon in New Zealand due to the historical challenges of correcting advanced keratoconus, prior to the technology we have now and the advent of corneal cross-linking. Indeed, sometimes my day resembles an episode of the TV series, The Walking Dead due to the number of previously deceased corneae strolling into my office!

Corneal grafts are volatile tissues, as there is always a risk of rejection, which requires ongoing observation. They don’t live forever either, as shown by a 2009 report in Ophthalmology which predicted graft survival to be 27% at 20 years and only 2% at 30 years¹. Incredibly, I have a few grafts under my care in their fifth decade of life, that still look superb. Credit goes to the eye care professionals involved in the past, I say!

Surgical techniques have advanced in the areas of corneal grafting with deep-anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) being performed more and more frequently these days. Traditional full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) remains the most commonly performed technique in New Zealand, although it decreased from 98.9% of all transplants in 1991 to 60.3% in 2015 (NZ Eye Bank Data).

Despite improved metrics for post-operative vision with DALK compared to PKP, it seems there are similar rates of graft failure³ and corneal astigmatism⁴ between the two surgeries suggesting that accurate specialty contact lens fitting will still be required in the near future at least.

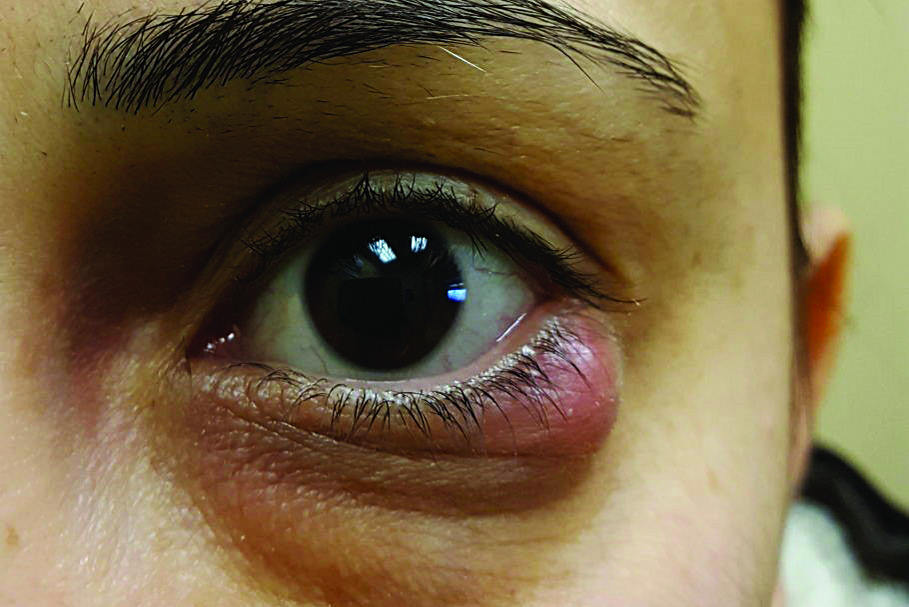

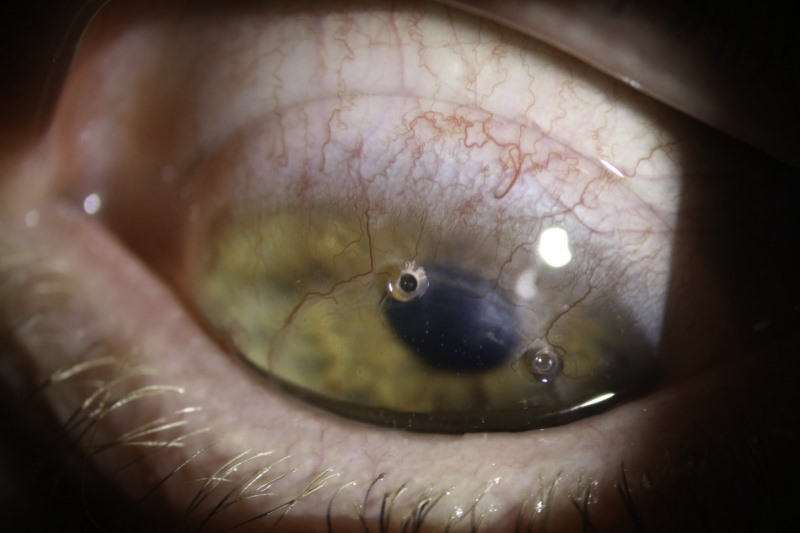

Contact lens technology is advancing too, with the larger corneo-scleral and scleral rigid contact lens being the hot topic in specialty lens circles these days. Many will extol the virtues of vaulting over the irregularity of a corneal graft with a large rigid lens. However, I believe that corneal grafts are one condition for which scleral rigid lenses should be used with caution. This is mainly due to the potential for hypoxic and physiological stress these lenses can induce to an unstable and fragile tissue (Fig 1). Don’t forget that endothelial cell counts are typically reduced post-keratoplasty, reaching levels of 865 cells/mm2 after 10 years in one study, a decrease of 61% from pre-surgical levels¹. A scleral lens design that will be perfectly adequate for a healthy keratoconic eye may provide insufficient oxygen in an older graft. Oxygen is not everything either, with many scleral lens experts internationally believing that limbal insult can cause just as many complications as hypoxia. Scleral lenses certainly have their place but always require careful design and relentless follow-up.

It is my belief that a well-fitted corneal rigid lens provides the best first choice for most corneal grafts. Corneal lenses offer great improvements in vision with acceptable comfort and generally a low effect on corneal physiology, hopefully facilitating a number of years of successful use.

So how do you best go about fitting a corneal graft with an rigid corneal lens, I hear you ask?

It is at this time that I thought it appropriate to live up to the ‘forum’ in this column’s name and ask some leading contact lens practitioners their thoughts on fitting grafts with RGPs. Here are their responses:

Paul Rose, CNZM

Kiwi contact lens practitioner extraordinaire, inventor of the Rose K Contact Lens and consultant to Menicon

In the first instance, I always try to use corneal lenses with a material Dk of at least 100, because these designs maximise tear exchange and correctly fitted provide ample oxygen to meet the corneal graft demands in by far the majority of cases. I fit a relatively large lens, usually at least 10.4mm, trying to land the lens on the normal cornea outside the graft junction. The lens design needs to incorporate reverse geometry in flatter base curves to minimise pooling over the central cornea which is so often oblate (Fig 2).

However, because grafts are frequently very irregular in shape with high degrees of toricity, location and stability are often major issues. This problem is exacerbated by the lens tending to centre over the highest area of the cornea, which is commonly along the graft/host interface.

If I cannot achieve a satisfactory fit with a corneal lens then I have no hesitation fitting a corneal scleral design which invariably overcomes the location and stability issues. Because tear exchange and movement is minimal with these designs, I will always use a material like Menicon Z (Dk 165) to avoid corneal anoxia. In rare cases, I will use a soft lens, which will frequently require an increased thickness to achieve acceptable vision, but this is never my first option due to the lower Dk these lenses provide.

Fig 2. This RGP lens needs a reverse geometry design to align the relatively flat graft curvature, courtesy of Paul Rose.

David Stephensen

Brisbane-based contact lens specialist, CCLSA Fellow, and QUT Masters of Optometry course lecturer

My approach to fitting RGP contact lenses, or any contact lenses, to a patient with corneal grafts is to always assume that the graft is at risk. The risks that may arise from contact lens wear include induced neo-vascularisation, contact lens related infiltrates or other inflammation. All of these conditions create a risk of graft rejection or incompetence. This shortens the graft-life expectancy and increases the total surgical burden on the patient over their lifetime.

My preferred approach to deciding on the type of RGP contact lens to use is based on using topographic modelling to forecast the probable lens movement on the eye. If I feel that I can fit a corneal RGP contact lens, I will do so as this spares the limbus from both mechanical irritation and contact lens-induced inflammation. I do not fit intralimbal or corneoscleral RGP contact lenses on corneal grafts as I feel the occurrence of inflammation and limbal mechanical interaction is too great. Should a corneal RGP not be suitable I prefer to utilise a mini-scleral contact lens. In either configuration, I use quadrant-specific designs to ensure as even a landing area and clearance as possible. This also has the advantage of holding the front optic zone as perpendicular to the visual axis as possible, providing a more ideal optical platform.

Andrew Sangster

Wellington-based contact lens specialist and proud owner of some of the loudest shirts in the industry

The challenge with fitting corneal grafts is the graft-host interface. The graft always seems thicker (no surprise there) and is often tilted. The consequent ‘shelving’ causes problems with fit centration, stability and lower lid comfort. The lens often traps air (which causes desiccation and vision issues) and risks blink-related mislocation. Also, there is the dreaded comfort/intolerance challenges that this corneal shape poses.

That said, we all have success stories, or sometimes just "not failure" stories! Grafted corneas are unfailingly unique. There is no guaranteed formula to absolute success I have found. My advice is to be fearless in trialing lenses and ensure you listen to your patient’s needs and expectations: how many hours will they need to wear their lenses; will they be wearing them in a dry/dusty/windy environment; do they have any allergies; has they had any previous graft-related problems; what are their visual requirements, etc.

I have found the PGA (Centra Post-Graft Aspheric - CLC NZ) lenses offer a good starting point, often with significant bi-sym tuck inferiorly. However, the fact is nothing beats a dynamic, on-eye assessment with fluorescein. Sometimes a small diameter lens centres on the graft really well, sometimes a larger diameter sits over the interface and locates well. It really is just being willing to put lenses on eyes and communicate with the patient that getting the best lens can be a journey.

Other clinical pearls

I thank Paul, David and Andrew for their contributions and I’m sure you will agree they offer a great insight into the skills needed to successfully fit corneal grafts: accurate lens design, careful consideration of corneal physiology and management of your patient’s visual requirements and expectations.

To add to these insights, here are some more clinical pearls I have found useful in my practice:

- Embrace corneal topography-guided lens design. Many corneal grafts have highly astigmatic surfaces or irregular elevations. Trial fitting spherical RPGs and even toric trial lenses can be a real guessing game. It’s even challenging to come up with a good starting point for a custom lens. But using software like Eyespace or the contact lens feature in Medmont Studio for example, allows you to quickly align the back optic zone radii closely to the graft curvature to minimise heavy bearing or pooling within the optic zone. The aim is to spread the pressure of the lens over as many points as possible, to improve comfort and stability of the lens.

- Be mindful of the graft diameter. As my contributors have touched upon, the graft-host junction can present a real challenge. Matching the back optic zone diameter of your lens to the diameter of the graft means your peripheral curves can then be fitted to the ‘normal’ host tissue, rather than the often proud and irregular graft/host junction. Alternatively, if there is a large graft, fit a smaller diameter lens to only the graft tissue and avoid the junction all together.

- Corneal topography will often struggle to measure the host tissue curvature due to the abrupt curvature change seen at the graft/host junction. This comes about from the ‘table-top’ configuration that many grafts have. Using composite maps on the Medmont software can assist here to get a better picture of the overall cornea (Fig 3). Anterior OCT can also help match peripheral curves to the host tissue curvature, as often excessive fluorescein or lifting-off during on-eye evaluation will not tell you much about what modifications to peripheral curves are required (Fig 4).

Fig 3. The advantage of composite topography maps with the E300 topographer. The composite map (right) shows a wider area that just the graft curvature seen on the single map (left)

Fig 4. Anterior OCT can be useful to see how well aligned your peripheral curves are and gain a better understanding of the graft-host junction.

A patient I fitted with new rigid corneal lenses earlier this year is a good example of these principles (see Fig 5.). She had bilateral PKP grafts done in the early 1980s and has been wearing RGPs ever since. Remarkably, her central corneae still look pristine, however both eyes’ host tissue have mild signs of quiescent blood vessels. As a teacher, her lenses are essential but they have always been prone to flicking out and moving around the eye. Her visit to my office was prompted by losing her left lens the week prior, when it went walk-about in the parking lot during a wet winter’s night.

Figure 5: The irregular corneal topography of my patient’s right eye.

Her current right lens was providing acceptable vision of 6/10 with some cylinder in the over-refraction. On the eye, however, it was quite mobile and showed a fluorescein pattern typical of a spherical lens on a toric cornea. The edges were also very loose leading to excessive lid interaction (Fig 6).

Figure 6: My patient’s original, rotationally-symmetrical right lens. Note the steep central fit along the 70° meridian, the significant edge lift and the inferior nasal mislocation.

Using lens design software, I was able to design a toric back optic zone radius (BOZR) that closely matched the corneal shape with reverse geometry peripheral curves steeper than the BOZR, that allowed the lens to lock into place and make the lens more stable (Fig 7). At the patient’s most recent appointment she was ecstatic with the results. The lenses were no longer flicking out, were far more comfortable on the eye and achieved excellent 6/6 vision in each eye. She could now drive comfortably at night which she was reluctant to do with her previous lenses! Her left lens had a BOZR difference of 3.6mm between the two meridians which highlights how extreme some of these designs have to be to fit an irregular corneal graft.

Fig 7. My patient’s new right lens. As one of my colleagues eloquently puts it, inevitably RGPs on grafts still end up looking like a ‘dog’s breakfast’, however this lens has a much better central alignment and better peripheral fit than the original due to the toric reverse geometry design

Conclusion

In summary, fitting corneal grafts with rigid contact lenses can often be a real challenge for patient and practitioners alike, but lead to great reward when often excellent vision and quality of life is restored. Be mindful of how different contact lens designs affect corneal physiology and don’t be afraid to experiment, as there is no one lens design or fitting philosophy that will work for all patients. Careful follow-up is crucial, and this includes patient education on the symptoms to watch out for if rejection looms.

Lastly, don’t forget if you or your patient’s nerves are frazzled after a particularly tough fitting appointment, there is always a friendly shrink a phone call away to talk and/or medicate all the woes away!

References:

Ophthalmology. 2009 Dec;116(12):2354-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.009. Epub 2009 Oct 7. Predicted long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Borderie VM1, Boëlle PY, Touzeau O, Allouch C, Boutboul S, Laroche L.

British Journal of Ophthalmology Published Online First: 15 September 2016. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309021. Kim BZ, Meyer JJ, Brookes NH, et al New Zealand trends in corneal transplantation over the 25 years 1991–2015

PLoS One. 2015; 10(1): e0113332. Published online 2015 Jan 29. Efficacy and Safety of Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty vs.Penetrating Keratoplasty for Keratoconus: A Meta-Analysis Hao Liu,‡ Yihui Chen,‡ Peng Wang, Bing Li, Weifang Wang, Yan Su, and Minjie Sheng*

Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013 Oct;27(5):322-30. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2013.27.5.322. Epub 2013 Sep 10. Comparison of clinical outcomes of same-size grafting between deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Oh BL1, Kim MK, Wee WR.

About the author:

Alex Petty is a Kiwi optometrist who graduated from the University of Auckland in 2010. He has an interest in specialty contact lenses, ortho-K and silmoparis.com myopia control.