A rare case of Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis

Case study: Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis following cataract surgery

By Dr Lucy Lu, Dr Jennifer Court and Professor Charles McGhee*

Here we present a rare case of post-cataract surgery, corneal wound infection caused by the non-tuberculous mycobacterium species Mycobacterium chelonae. This case illustrates the difficulties in diagnosis and treatment of this uncommon condition to increase awareness of this potentially devastating infection among optometrists and ophthalmologists.

Case history

A usually fit and well, 85-year-old, New Zealand European female presented with redness, pain and reduced vision in her left eye, eight weeks after routine, uncomplicated, cataract phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation.

Visual acuity OS at presentation was reduced to 6/30 unaided, 6/15 with pinhole (previously 6/7.5 corrected post-op). The left cornea had a 1.0 x 2.8mm stromal infiltrate in the temporal clear corneal wound site, without an overlying epithelial defect. The anterior chamber exhibited 2+ cells but no hypopyon. The vitreous was quiet and the fundus examination was normal. She was admitted to hospital and treated with intensive topical antibiotic drops (hourly cefuroxime 5% and tobramycin 1.36%). However, the intraocular inflammation worsened so she underwent anterior chamber washout, vitrectomy and administration of intravitreal antibiotics (ceftazidime and vancomycin). Oral doxycycline, ciprofloxacin and prednisone were added. Surprisingly, aqueous and vitreous samples were entirely negative for bacterial and fungal culture as well as for viral PCR.

After slow improvement, she was discharged on day 16 on topical ciprofloxacin and prednisolone 1%. She was monitored closely as an outpatient and the infection waxed and waned over the subsequent two months (Figs 1 and 2). A large corneal biopsy also failed to identify any causative organism. Therefore, after 13 weeks of treatment, ciprofloxacin was cautiously tapered and stopped, however, the infection recurred with greater severity with an overlying corneal melt and the prospect of corneal perforation. Subsequently, a superficial keratectomy, accompanied by a focal, partial-thickness, tectonic corneal graft (5mm), was performed to excise the majority of the lesion, approximately four months after initial presentation.

Two weeks later, white flecks were noted in the graft-host-interface (Fig 3) and a rapidly growing mycobacterium species, Mycobacterium chelonae was also isolated from the superficial keratectomy. This isolate was notably resistant to ciprofloxacin and doxycycline, but sensitive to clarithromycin, tobramycin and linezolid on standard MIC (mean inhibitory concentration) testing. Therefore, intensive topical tobramycin and linezolid were started, and topical prednisolone withheld.

Despite intensive, appropriate, dual-antibiotic topical treatment the inflammation increased and the overlying graft became oedematous and opaque (Figs 4a and 4b). Consequently, the lamellar graft was removed to reduce the infective load and allow better drug penetration to the underlying host cornea. After an extended two-month course of treatment, the infection gradually settled, almost 10 months after her initial cataract surgery (Fig 5). Her vision at this stage was 6/15 unaided, 6/9 pinhole and her eye was comfortable. She is expected to continue on low dose topical antibiotics, under close monitoring, for up to a year.

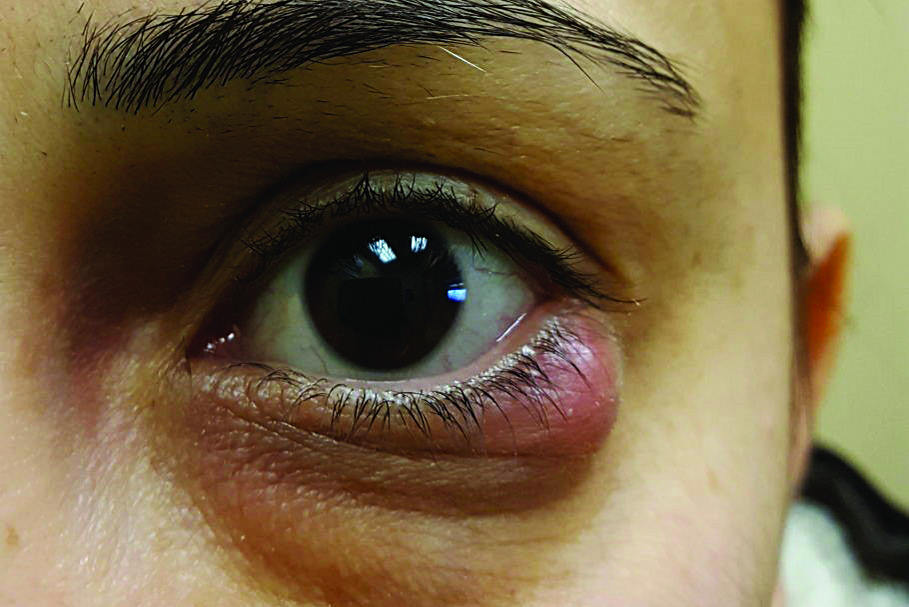

Fig 1. Recurrence of dense stromal infiltrate at the temporal clear corneal wound (arrow) with keratic precipitates, two weeks after discharge from hospital, while on treatment with topical ciprofloxacin

Fig 2. Apparent early control of keratitis after three months of treatment. Note the quiescent eye but suspicious white deposits in stroma. Ciprofloxacin was stopped at this stage

Fig 3. Appearance of the (5mm) temporal, lamellar tectonic corneal graft post-op day 19, demonstrating white interface specks on retro-illumination, heralding the return of infection

Fig 4a. Progessive infection with development of interface fluid affecting the temporal, lamellar tectonic corneal graft with loosening of sutures (6 weeks post-op)

Fig 4b. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) image through infected graft, demonstrating fluid in the graft-host interface

Fig 5. After two months of continuous topical Linezolid and Tobramycin, the base of the previous patch graft site had epithelialised and was clinically free of infection

Discussion

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) refers to a group of Mycobacterium species other than the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. NTM exist ubiquitously in the environment including in soil and drinking water. They are rare causes of systemic and ocular infections, particularly related to trauma and surgery1. The Mycobacterium chelonae species is an insidious yet aggressive pathogen that has been reported as a devastating cause of post-LASIK and post-cataract surgery keratitis and endophthalmitis2-6. There are several cases of Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis after clear cornea cataract surgery reported in the literature, many requiring significant intervention such as corneal transplant, but typically with poor visual outcomes4-6.

Known risk factors for developing mycobacterial keratitis include trauma, ocular surgery, poor tear film integrity, inappropriate use of topical corticosteroids and contact lens use4. Systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus or immunosuppression increase the susceptibility to infection. Our patient did not have any of these risk factors, other than routine post-operative steroid drops.

Post-operative Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis has an insidious onset, with variable time between surgery and onset of symptoms, from days to months. The affected cornea may exhibit a “cracked windshield” appearance around the edges of a stromal infiltrate, often without an overlying epithelial defect. Infiltrates may have irregular margins or stellate lesions, mimicking a fungal keratitis1.

NTM infections are particularly dangerous because most routinely used topical antibiotics are ineffective against them, and antibiotic resistance is a significant issue7. A review of in vitro microbiological susceptibilities of NTM showed the following susceptibilities: clarithromycin (93%), amikacin (81%), linezolid (36%), moxifloxacin (21%), and ciprofloxacin (10%). In the M. abscessus/chelonae subgroup, only 1% were susceptible to ciprofloxacin8. In addition, Mycobacterium chelonae can be difficult to culture, with fastidious growth requirements, which increases the risk of false negative reports and delayed diagnosis as in this case7.

Mycobacteria keratitis requires aggressive treatment, ideally with multiple fortified topical antibiotics with consideration of systemic cover (such as oral clarithromycin) if severe7, 8. An extended treatment course is required.

As illustrated in the presented case, Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis can take a prolonged, waxing and waning course that may falsely reassure the clinician of impending resolution. Negative corneal scrapes in a non-responding infection warrants surgical biopsy to enable correct diagnosis and prevent complications, such as infective scleritis or endophthalmitis. Surgical debridement of infected tissue may reduce the bacterial load and also improve antibiotic penetration into deep stroma, where organisms may have been seeded into a surgical wound.

While mycobacterial ocular infection is rare, it must be kept in mind by all ophthalmic health providers when evaluating any atypical post-laser or post-surgical infection. NTM are a particular diagnostic and treatment challenge compared to other microbes due to delays in pathogen identification, multiple antibiotic resistances and a higher likelihood to require surgical intervention. Therefore, maintaining a high level of suspicion in unusual cases, obtaining early, accurate microbial diagnosis, with aggressive and extended antimicrobial treatment and early surgical intervention are key to minimising morbidity and maximizing visual outcome.

References

- Kheir WJ, Sheheitli H, Abdul Fattah M, Hamam RN. Nontuberculous mycobacterial ocular infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:164989.

- Freitas D, Alvarenga L, Sampaio J, Mannis M, Sato E, Sousa L, et al. An outbreak of Mycobacterium chelonae infection after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003 Feb;110(2):276-85.

- John T1, Velotta E. Nontuberculous (atypical) mycobacterial keratitis after LASIK: current status and clinical implications. Cornea. 2005 Apr;24(3):245-55.

- Martinez JD, Amescua G, Lozano-Cárdenas J, Suh LH. Bilateral Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis after phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2017;2017:6413160.

- Servat JJ, Ramos-Esteban JC, Tauber S, Bia FJ. Mycobacterium chelonae-Mycobacterium abscessus complex clear corneal wound infection with recurrent hypopyon and perforation after phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005 Jul;31(7):1448-51.

- Ramaswamy AA, Biswas J, Bhaskar V, Gopal L, Rajagopal R, Madhavan HN. Postoperative Mycobacterium chelonae endophthalmitis after extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Ophthalmology. 2000 Jul;107(7):1283-6.

- De la Cruz J, Behlau I, Pineda R. Atypical mycobacteria keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis unresponsive to fourth-generation fluoroquinolone therapy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007 Jul;33(7):1318-21.

- Girgis DO, Karp CL, Miller D. Ocular infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria: update on epidemiology and management. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul;40(5):467-75.

*Dr Lucy Lu is an ophthalmology clinical research fellow at the University of Auckland with an interest in corneal and anterior segment disease and surgery. Dr Jennifer Court is a senior corneal fellow at the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Auckland. Professor Charles McGhee is head of the Department of Ophthalmology at Auckland University, a consultant ophthalmologist with the ADHB and chair of RANZCO’s special interest group in cornea, contact lenses, and cataract and refractive surgery