Adjusting eyelid position brings dry eye relief

Dry eye disease (DED) is multifactorial in origin and, while intrinsic ocular surface pathology often garners the most attention, mechanical contributors, particularly those related to eyelid position and function, are sometimes underrecognised. In clinical oculoplastics practice, eyelid malpositions, such as entropion, ectropion and lid laxity, are common findings, especially in the elderly, and are frequently implicated in DED1.

The eyelids play an important role in maintaining ocular surface health2. They protect the corneal surface, distribute the tear film, express meibomian lipids and facilitate uniform corneal coverage through blink mechanics. Eversion of the lower lid (ectropion) can displace the punctum, leading to impaired tear clearance, epiphora and increased tear film osmolarity3. Entropion, on the other hand, can cause the eyelashes to abrade the corneal surface, inducing inflammation and epithelial breakdown4. Lid laxity contributes by preventing proper apposition of the lid and lid margin to the globe, allowing for poor tear distribution, increased evaporation and exposure keratopathy.

Many of these anatomical abnormalities are amenable to surgical correction, often with excellent outcomes. Even mild lower-lid malposition may be sufficient to perpetuate ocular surface symptoms and justify intervention. Procedures, such as lateral tarsal strip or lower lid retractor reinsertion, can restore normal lid-globe contact and reduce the dysfunctional anatomy, fueling the vicious cycle of DED3,4. By employing these simple, yet powerful oculoplastic techniques, significant improvements can be made to patient quality of life.

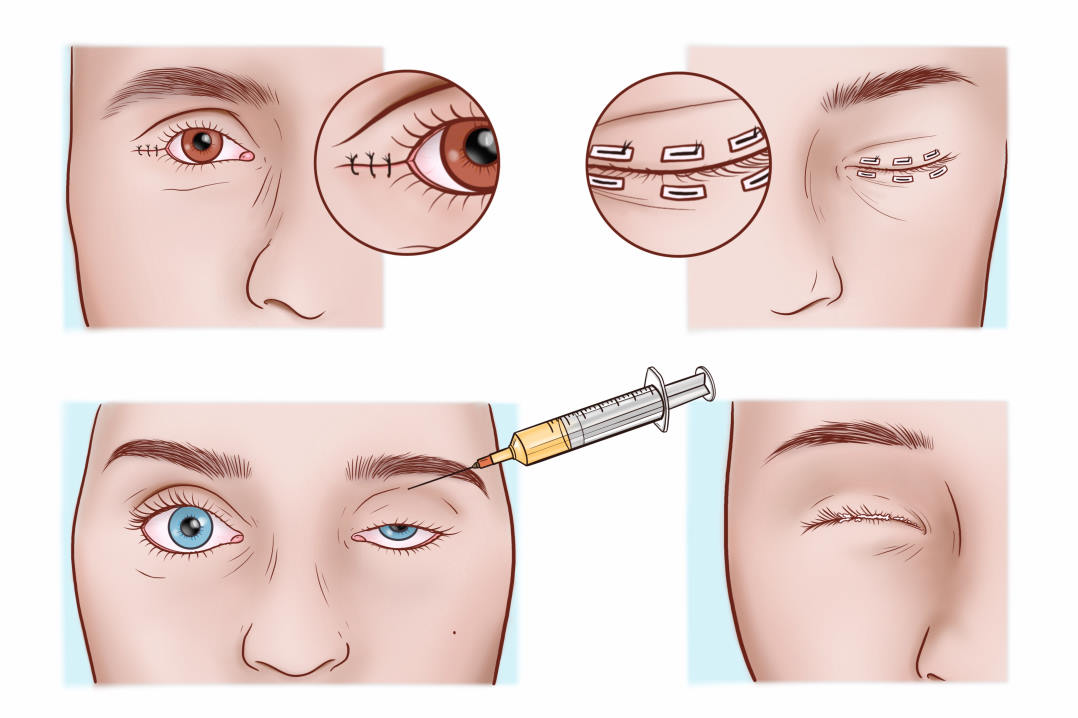

One technique we find particularly valuable in cases refractory to standard treatment is the temporary tarsorrhaphy5. By partially or completely closing the eyelid, the palpebral fissure can be reduced, thereby minimising tear film evaporation and facilitating epithelial healing6. It is a versatile and reversible procedure that can significantly improve epithelial health in patients with severe dry eye, facial burns or lagophthalmos. The relative ease and reversibility of this intervention make it especially useful in frail or systemically unwell patients, or when corneal integrity is at risk. Temporary tarsorrhaphy can be achieved using sutures or cyanoacrylate glue, each of which can be performed in an outpatient setting. Glue-based tarsorrhaphy is especially suitable for short-term closure in small nonhealing defects, providing rapid intervention with minimal invasiveness.

Another non-surgical alternative is the use of botulinum toxin injections into the levator palpebrae superioris muscle to induce temporary ptosis7. This technique is particularly helpful for patients who are unwilling or medically unfit for surgical intervention. For more chronic cases, permanent tarsorrhaphy is performed surgically by debriding the intermarginal strip of the eyelid and suturing the lids together, with or without bolsters, to maintain closure. Depending on the location of the epithelial defect, medial, lateral, pillar or complete tarsorrhaphy can be performed to ensure optimal coverage. Given its safety profile, accessibility and versatility, tarsorrhaphy should be considered early in the course of treatment when epithelial healing is delayed, as timely intervention can prevent more serious complications and the need for more invasive procedures.

Primary eyecare providers are well-positioned to recognise eyelid-related contributions to dry eye. When patients fail to respond to conventional therapy, a targeted assessment of lid position, blink completeness and orbicularis function can be beneficial. Early referral to an oculoplastic surgeon can prevent long-term damage and improve quality of life. As our understanding of DED continues to evolve, it is essential to recognise that anatomical integrity underpins ocular surface function. Anatomical abnormalities of the eyelids should be considered in any comprehensive approach to dry eye management.

References

1. Damasceno, RW, et al. Involutional entropion and ectropion of the lower eyelid: prevalence and associated risk factors in the elderly population. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2011. 27(5): p. 317-20.

2. Knop E, et al. The lid margin is an underestimated structure for preservation of ocular surface health and development of dry eye disease. Dev Ophthalmol, 2010. 45: p. 108-122.

3. Khan AZ, et al. Ectropion. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen, 2024. 144(1).

4. Khan AZ, et al., Entropion. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen, 2024. 144(15).

5. Acharya M, Gour AW, Dave A.Commentary: Tarsorrhaphy: A stitch in time. Indian J Ophthalmol, 2020. 68(1): p. 33-34.

6. Robinson C, et al.Temporary Eyelid Closure Appliqué. Archives of Ophthalmology, 2006. 124(4): p. 546-549.

7. Kirkness CM, et al. Botulinum toxin A-induced protective ptosis in corneal disease. Ophthalmology, 1988. 95(4): p. 473-80.

Dr Ayyad Khan, department of ophthalmology at Østfold Hospital Trust in Moss, Norway, has a special interest in oculoplastic surgery and dry eye disease.

Dr Elin Bohman director of Oculoplastic and Orbital Services at St Erik Eye Hospital in Stockholm has a special interest in oculoplastic surgery.

Professor Tor Utheim is the co-founder of the Norwegian Dry Eye Clinic and has a special interest in dry eye disease.