CASE STUDY: non-neovascular subretinal fluid in AMD

A 65-year-old European man was referred to the retinal clinic for ongoing age-related macular degeneration (AMD) management. On a routine examination by his optometrist, he was found to have bilateral subretinal fluid (SRF) and drusen. He was asymptomatic with visual acuity of 6/9 in both eyes. A single set of bilateral intravitreal Avastin injections was given elsewhere prior to the referral.

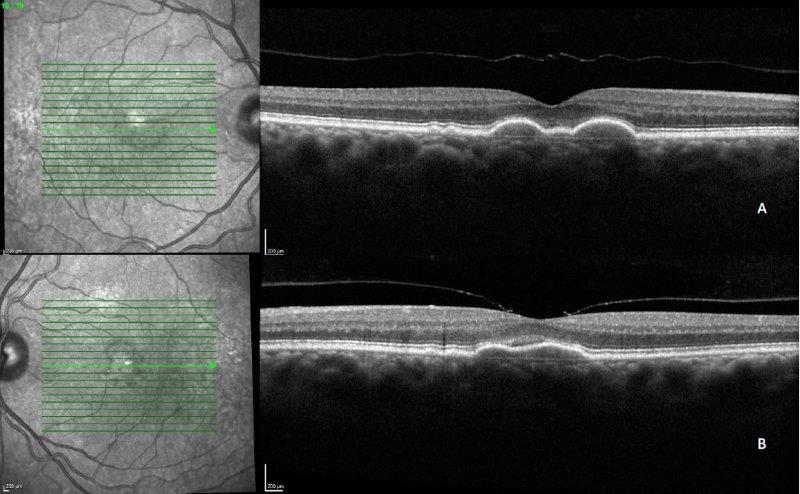

Examination showed drusen and no haemorrhage, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed bilateral drusen and subretinal fluid (Fig 1).

So are ongoing intravitreal anti-VEGF injections required in this case?

Research commentary

The diagnosis of neovascular AMD (nAMD) is traditionally made on fundus fluorescein angiogram (FFA) and this remains the confirmatory diagnostic test as per the American Academy of Ophthalmology1,2. However, FFA is an invasive test requiring specialised equipment, restricting its availability. OCT has now been adopted in clinical practice for the diagnosis of nAMD but false positives have been reported, leading to unnecessary anti-VEGF treatments1. In particular, the presence of SRF in AMD, without other features of neovascular changes, is interpreted as nAMD and an indication to start anti-VEGF injections.

It has now been recognised that patients with non-nAMD can develop subretinal fluid and these patients do not require anti-VEGF injections. An international multicentre study recruited 45 eyes from 45 patients with subretinal fluid and intermediate AMD deemed non-neovascular, as confirmed by clinical examination (absence of haemorrhage), OCT angiography, FFA or indocyanine green angiography3. The mean follow up period for these patients was 49 months.

Three distinct patterns of SRF were identified in this study:

- Fluid located at the apex of a drusenoid pigment epithelium detachment (PED)

- Fluid located at the angle of a large druse or drusenoid PED or within the pocket or crypt between confluent drusen

- Fluid located in a shallow or low-lying drape over confluent drusen

Instead of fibrosis (which would be expected in untreated nAMD), atrophy is the common feature in patients with non-neovascular AMD. Over the follow-up period, 60% of eyes showed collapse of the associated druse or drusenoid PED; and 53% of eyes developed complete or incomplete retinal pigment epithelium and outer retinal atrophy (RORA). Furthermore, many of the patients with non-neovascular AMD had other OCT biomarkers for atrophy, but none of these lesions required anti-VEGF injections over the follow up period.

Conclusions

The result of this study suggests that rather than reflexively proceeding to anti-VEGF injections when there is SRF in AMD, clinicians should seek confirmatory signs of neovascularisation prior to treatment. These signs include haemorrhages on clinical examinations, subretinal hyperreflective material and double layer signs on OCT, and the presence of neovascularisation on OCT angiography, FFA or ICG.

In particular, clinicians should be cautious regarding starting anti-VEGF in cases of SRF over areas of drusen without other OCT features of neovascularisation. Many of these cases will turn out to be non-neovascular, so injection therapy will be unnecessary.

Case outcome

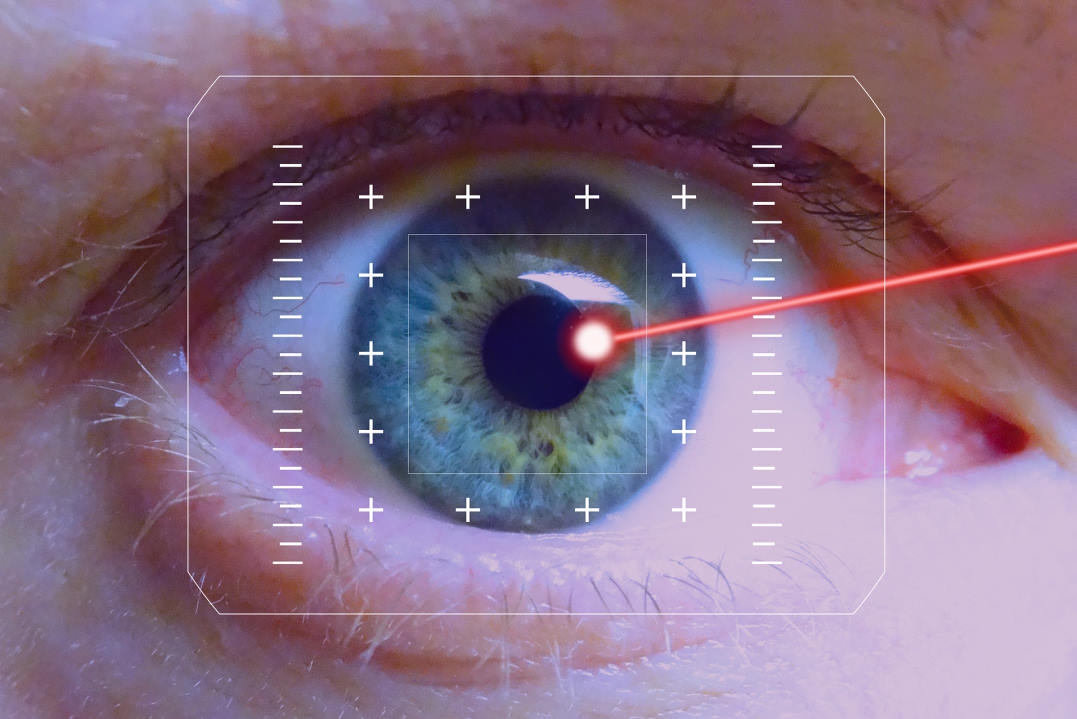

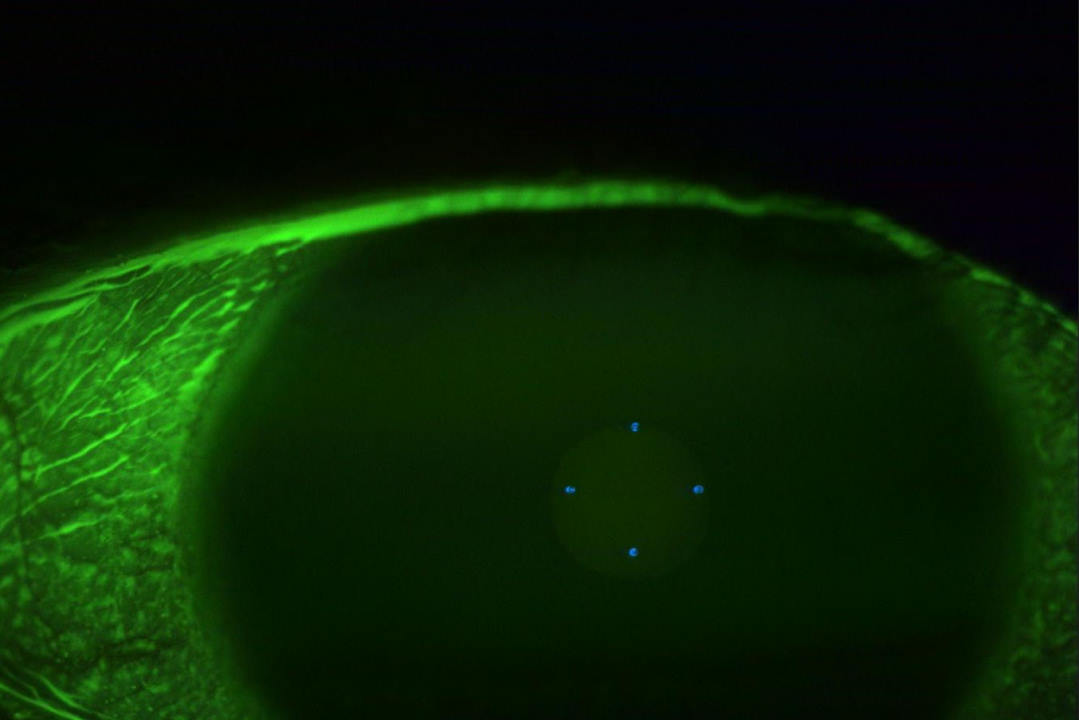

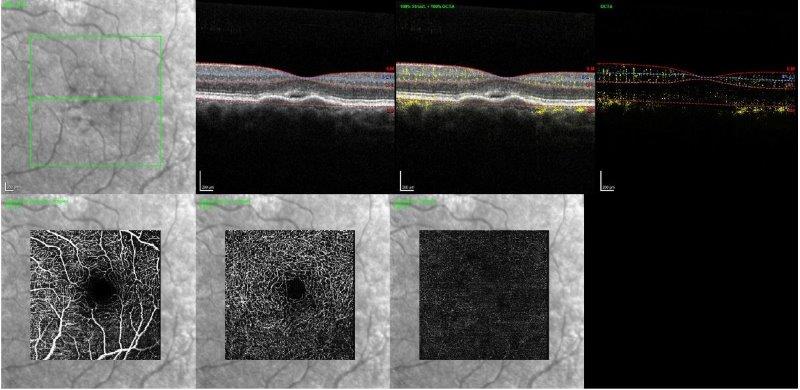

Fig 2. OCT angiography of the left eye at presentation with no macular neovascularisation. OCTA findings in the right eye were similar to the left

In the case presented above, careful analysis of the OCT showed no double layer sign or subretinal hyperreflective material. Examination of the fundus showed no haemorrhage. As a result, I suspected that the SRF was non-neovascular and no treatment was required. I further obtained an OCT angiography (Fig 2), which did not show any macular neovascular membrane.

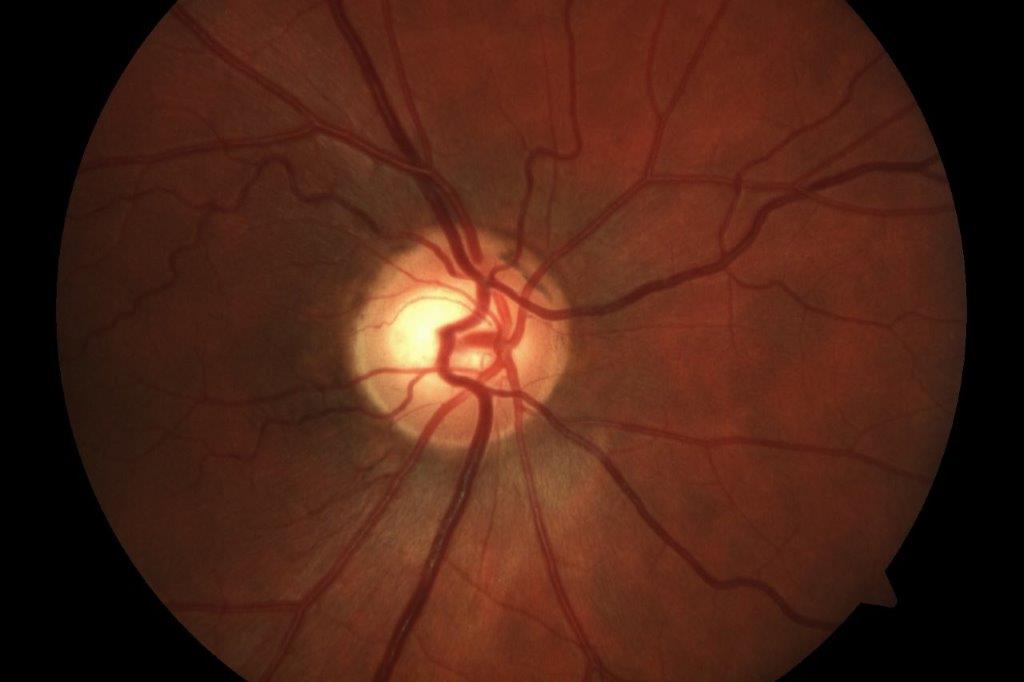

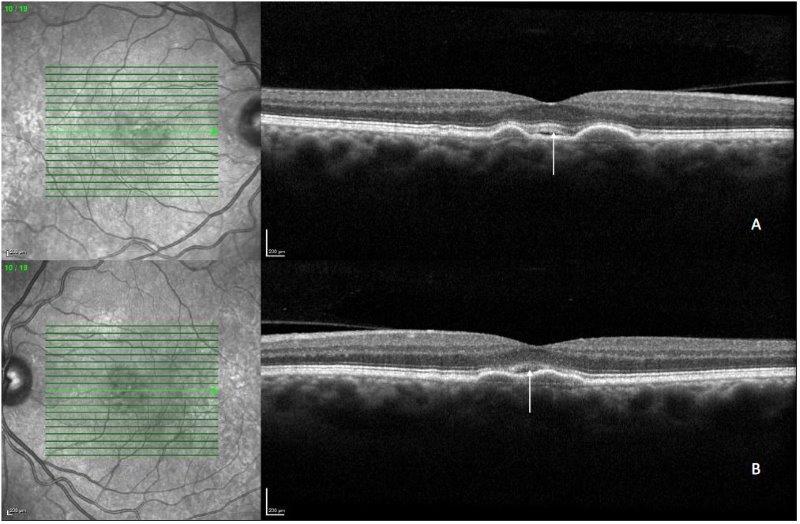

Fig 3. OCT image of the right (A) and left eye (B) at 18-month follow-up

This patient was monitored over a period of 18 months, in which the SRF did not worsen (Fig 3). The amount of drusen fluctuated over this period of time but there was no atrophy. No anti-VEGF therapy was required over the follow-up period.

References

1. Sivaprasad, S. et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Monitoring Tests of Fellow Eyes in Patients with Unilateral Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Early Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Study. Ophthalmology 128, 1736–1747 (2021).

2. Flaxel, C. J. et al. Age-Related Macular Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 127, P1–P65 (2020).

3. Hilely, A. et al. Non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration with subretinal fluid. Br. J. Ophthalmol. bjophthalmol-2020-317326 (2020) doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317326.

Dr Leo Sheck specialises in medical retina, genetic eye disease, electrodiagnostics for complex retina and optic nerve diseases and cataract surgery, especially with co-existing retinal diseases. He consults for ADHB and Retina Specialists, and is chair of the NZ Save Sight Society.